| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Sparta describes the history of the ancient Doric Greek city-state known as Sparta from its beginning in the legendary period to its incorporation into the Achaean League under the late Roman Republic, as Allied State, in 146 BC, a period of roughly 1000 years. Since the Dorians were not the first to settle the valley of the Eurotas River in the Peloponnesus of Greece, the preceding Mycenaean and Stone Age periods are described as well. Sparta went on to become a district of modern Greece. Brief mention is made of events in the post-classical periods.

Dorian Sparta rose to dominance in the 6th century BC. At the time of the Persian Wars, it was the recognized leader by assent of the Greek city-states. It subsequently lost that assent through suspicion that the Athenians were plotting to break up the Spartan state after an earthquake destroyed Sparta in 464 BC. When Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War, it secured an unrivaled hegemony over southern Greece.[1] Sparta's supremacy was broken following the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC.[1] It was never able to regain its military superiority[2] and was finally absorbed by the Achaean League in the 2nd century BC.

Prehistoric period

Stone age in Sparta

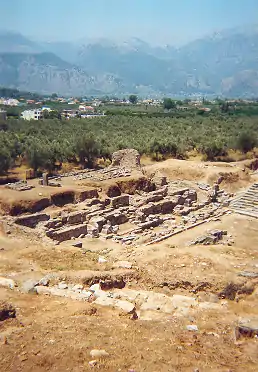

The earliest certain evidence of human settlement in the region of Sparta, consists of pottery dating from the Middle Neolithic period found in the vicinity of Kouphovouno some two kilometres southwest of Sparta.[3]

Legendary account

According to myth, the first king of the region later to be called Laconia, but then called Lelegia was the eponymous King Lelex. He was followed, according to tradition, by a series of kings allegorizing several traits of later-to-be Sparta and Laconia, such as the Kings Myles, Eurotas, Lacedaemon and Amyclas of Sparta. The last king from their family was Tyndareus, father of Castor and Clytemnestra and foster-father to Pollux and Helen of Troy. Female figures in this legendary ancestry include the nymph Taygete (mother of Lacedaemon), Sparta (the daughter of Eurotas) and Eurydice of Argos (grandmother of Perseus).

Later the Achaeans, associated with Mycenaean Greece, immigrated from the north and replaced the Lelegians as ruling tribe. Helen, daughter of Zeus and Leda, would marry Menelaos and thus invite the Atreidae to the Laconian throne. In the end the Heracleidae, commonly identified with the Dorians, would seize the land and the throne of Laconia and found the city-state of Sparta proper. The last Atreidae Tisamenus and Penthilus, according to myth, would lead the Achaeans to Achaea and Asia minor, whereas the Heraclids Eurysthenes and Procles founded the Spartan kingly families of the Agiad and Eurypontid dynasties respectively.

Mycenaean period in Sparta

Dorian invasion

The Pre-Dorian, supposedly Mycenaean, civilization seems to have fallen into decline by the late Bronze Age, when, according to Herodotus, Macedonian tribes from the north marched into Peloponnese, where they were called Dorians and subjugating the local tribes, settled there.[4]

Tradition describes how, some sixty years after the Trojan War, a Dorian migration from the north took place and eventually led to the rise of classical Sparta.[5] This tradition is, however, contradictory and was written down at a time long after the events they supposedly describe. Hence skeptics like Karl Julius Beloch have denied that any such event occurred.[6] Chadwick has argued, on the basis of slight regional variations that he detected in Linear B, that the Dorians had previously lived in the Dorian regions as an oppressed majority, speaking the regional dialect, and emerged when they overthrew their masters.[7]

Dark age in Sparta

Archeologically, Sparta itself begins to show signs of settlement only around 1000 BC, some 200 years after the collapse of Mycenaean civilization.[8] Of the four villages that made up the Spartan polis, Forrest suggests that the two closest to the Acropolis were the originals, and the two more far-flung settlements were of later foundation. The dual kingship may originate in the fusion of the first two villages.[9] One of the effects of the Mycenaean collapse had been a sharp drop in population. Following that, there was a significant recovery, and this growth in population is likely to have been more marked in Sparta, as it was situated in the most fertile part of the plain.[10]

Between the 8th and 7th centuries BC the Spartans experienced a period of lawlessness and civil strife, later testified by both Herodotus and Thucydides.[11] As a result, they carried out a series of political and social reforms of their own society which they later attributed to a semi-mythical lawgiver, Lycurgus.[12] These reforms mark the beginning of the history of Classical Sparta.

Proto-historic period

The reforms of Lycurgus

It is during the reign of King Charillos,[13] that most ancient sources place the life of Lycurgus. Indeed, the Spartans ascribed their subsequent success to Lycurgus, who instituted his reforms at a time when Sparta was weakened by internal dissent and lacked the stability of a united and well-organized community.[14] There are reasons to doubt whether he ever existed, as his name derives from the word for "wolf" which was associated with Apollo, hence Lycurgus could be simply a personification of the god.[15]

J. F. Lazenby suggests, that the dual monarchy may date from this period as a result of a fusion of the four villages of Sparta which had, up until then, formed two factions of the villages of Pitana-Mesoa against the villages of Limnai-Konoura. According to this view, the Kings, who tradition says ruled before this time, were either totally mythical or at best factional chieftains.[16] Lazenby further hypothesizes that other reforms such as the introduction of the Ephors were later innovations that were attributed to Lycurgus.[17]

Expansion of Sparta in the Peloponnesus

The Dorians seem to have set about expanding the frontiers of Spartan territory almost before they had established their own state.[18] They fought against the Argive Dorians to the east and southeast, and also the Arcadian Achaeans to the northwest. The evidence suggests that Sparta, relatively inaccessible because of the topography of the plain of Sparta, was secure from early on: it was never fortified.[18]

Sparta shared the plain with Amyklai which lay to the south and was one of the few places to survive from Mycaenean times and was likely to be its most formidable neighbor. Hence the tradition that Sparta, under its kings Archelaos and Charillos moved north to secure the upper Eurotas valley is plausible.[10] Pharis and Geronthrae were then taken and, though the traditions are a little contradictory, also Amyklai which probably fell in about 750 BC. It is probable that the inhabitants of Geronthrae were driven out while those of Amyklai were simply subjugated to Sparta.[19] Pausanias portrays this as a "Dorian versus Achaean" conflict.[20] The archaeological record, however, throws doubt on such a cultural distinction.[21]

7th century BC

Tyrtaeus tells that the war to conquer the Messenians, their neighbors on the west, led by Theopompus, lasted 19 years and was fought in the time of the fathers of our fathers. If this phrase is to be taken literally, it would mean that the war occurred around the end of the 8th century BC or the beginning of the 7th.[22] The historicity of the Second Messenian War was long doubted, as neither Herodotus or Thucydides mentions a second war. However, in the opinion of Kennell, a fragment of Tyrtaeus (published in 1990) gives us some confidence that it really occurred (probably in the later 7th century).[23] It was as a result of this second war, according to fairly late sources, that the Messenians were reduced to the semi slave status of helots.[23]

Whether Sparta dominated the regions to its east at the time is less settled. According to Herodotus the Argives' territory once included the whole of Cynuria (the east coast of the Peloponnese) and the island of Cythera.[24] Cynuria's low population – apparent in the archaeological record – does suggest that the zone was contested by the two powers.[25]

In the Second Messenian War, Sparta established itself as a local power in Peloponnesus and the rest of Greece. During the following centuries, Sparta's reputation as a land-fighting force was unequaled.[26]

6th century BC

Peloponnesian League

Early in the 6th century BC, the Spartan kings Leon and Agasicles made a vigorous attack on Tegea, the most powerful of the Arcadian cities.[14] For some time Sparta had no success against Tegea and suffered a notable defeat at the Battle of the Fetters—the name reflected Spartan intentions to force the Tegea to recognise it as hegemon.[27] For Forrest this marked a change in Spartan policy, from enslavement to a policy of building an alliance that led to the creation of the Peloponesian League. Forrest, hesitantly attributes this change to Ephor Chilon.[28] In building its alliance, Sparta gained two ends, protection of its conquest of Mesene and a free hand against Argos.[29] The Battle of the Champions won about 546 BC (that is at the time that the Lydian Empire fell before Cyrus of Persia) made the Spartans masters of the Cynuria, the borderland between Laconia and Argolis.[29]

In 494 BC, King Cleomenes I, launched what was intended to be a final settling of accounts with the city of Argos – an invasion, with the capture of the city itself, as the objective.[30] Argos did not fall but her losses in the Battle of Sepeia would cripple Argos militarily, and lead to deep civil strife for some time to come.[31] Sparta had come to be acknowledged as the leading state of Hellas and the champion of Hellenism. Croesus of Lydia had formed an alliance with it. Scythian envoys sought its aid to stem the invasion of Darius; to Sparta, the Greeks of Asia Minor appealed to withstand the Persian advance and to aid the Ionian Revolt; Plataea asked for Sparta's protection; Megara acknowledged its supremacy; and at the time of the Persian invasion under Xerxes no state questioned Sparta's right to lead the Greek forces on land or at sea.[14]

Expeditions outside the Peloponnese

At the end of the 6th century BC, Sparta made its first intervention north of the Isthmus when it aided in overthrowing the Athenian tyrant Hippias in 510 BC.[32] Dissension in Athens followed with conflict between Kleisthenes and Isagoras. King Cleomenes turned up in Attica with a small body of troops to back the more conservative Isagoras, whom Cleomenes successfully installed in power. The Athenians, however, soon tired of the foreign king, and Cleomenes found himself expelled by the Athenians.

Cleomenes then proposed an expedition of the entire Peloponnesian League, with himself and his co-King Demaratos in command and the aim of setting up Isagoras as tyrant of Athens. The specific aims of the expedition were kept secret. The secrecy proved disastrous and as dissension broke out the real aims became clearer. First the Corinthians departed. Then a row broke out between Cleomenes and Demaratos with Demaratos too, deciding to go home.[33] As a result of this fiasco the Spartans decided in future not to send out an army with both Kings at its head. It also seems to have changed the nature of the Peloponnesian League. From that time, major decisions were discussed. Sparta was still in charge, but it now had to rally its allies in support of its decisions.[34]

5th century BC

Persian Wars

Battle of Marathon

After hearing a plea for help from Athens who were facing the Persians at Marathon in 490 BC, Sparta decided to honor its laws and wait until the moon was full to send an army. As a result, Sparta's army arrived at Marathon after the battle had been won by the Athenians.

Battle of Thermopylae

In the second campaign, conducted ten years later by Xerxes, Sparta faced the same dilemma. The Persians inconveniently chose to attack during the Olympic truce which the Spartans felt they must honor. Other Greek states which lacked such scruples were making a major effort to assemble a fleet – how could Sparta not contribute on land when others were doing so much on sea?[35] The solution was to provide a small force under Leonidas to defend Thermopylae. However, there are indications that Sparta's religious scruples were merely a cover. From this interpretation, Sparta believed that the defense of Thermopylae was hopeless and wished to make a stand at the Isthmus, but they had to go through the motions or Athens might ally itself with Persia. The loss of Athens's fleet would simply be too great a loss to the Greek resistance to be risked.[36] The alternative view is that, on the evidence of the actual fighting, the pass was supremely defensible, and that the Spartans might reasonably have expected that the forces sent, would be adequate.[37]

In 480 BC, a small force of Spartans, Thespians, and Thebans led by King Leonidas (approximately 300 were full Spartiates, 700 were Thespians, and 400 were Thebans; these numbers do not reflect casualties incurred prior to the final battle), made a legendary last stand at the Battle of Thermopylae against the massive Persian army, inflicting very high casualties on the Persian forces before finally being encircled.[38] From then on Sparta took a more active share and assumed the command of the combined Greek forces by sea and land. The decisive victory of Salamis did not change Sparta's essential dilemma. Ideally, they would wish to fight at the Isthmus where they would avoid the risk of their infantry being caught in the open by the Persian cavalry.

Battle of Plataea

However, in 479 BC, the remaining Persian forces under Mardonius devastated Attica, Athenian pressure forced Sparta to lead an advance.[39] The outcome was a standoff where both the Persians and the Greeks attempted to fight on favorable terrain, and this was resolved when the Persians attacked during a botched Greek withdrawal. In the resulting Battle of Plataea the Greeks under the generalship of the Spartan Pausanias overthrew the lightly armed Persian infantry, killing Mardonius.[40] The superior weaponry, strategy, and bronze armour of the Greek hoplites and their phalanx had proved their worth with Sparta assembled at full strength and leading a Greek alliance against the Persians. The decisive Greek victory at Plataea put an end to the Greco-Persian War along with Persian ambition of expanding into Europe. Even though this war was won by a pan-Greek army, credit was given to Sparta, who besides being the protagonist at Thermopylae and Plataea, had been the de facto leader of the entire Greek expedition.[41]

Battle of Mycale

In the same year a united Greek fleet under the Spartan King, Leotychidas, won the Battle of Mycale. When this victory led to a revolt of the Ionian Greeks it was Sparta that rejected their admission to the Hellenic alliance. Sparta proposed that they should abandon their homes in Anatolia and settle in the cities that had supported the Persians.[42] It was Athens who, by offering these cities alliance sowed the seeds of the Delian League.[43] In 478 BC, the Greek fleet led by Pausanias, the victor of Plataea, mounted moves on Cyprus and Byzantium. However, his arrogant behavior forced his recall. Pausanias had so alienated the Ionians that they refused to accept the successor, Dorcis, that Sparta sent to replace him. Instead those newly liberated from Persia turned to Athens.[44] The sources give quite divergent impressions about Spartan reactions to Athens' growing power and this may reflect the divergence of opinion within Sparta.[45] According to this view, one Spartan faction was quite content to allow Athens to carry the risk of continuing the war with Persia while an opposing faction deeply resented Athens' challenge to their Greek supremacy.[46]

In later Classical times, Sparta along with Athens, Thebes, and Persia had been the main powers fighting for supremacy against each other. As a result of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta, a traditionally continental culture, became a naval power. At the peak of its power Sparta subdued many of the key Greek states and even managed to overpower the elite Athenian navy. By the end of the 5th century BC, it stood out as a state which had defeated the Athenian Empire and had invaded the Persian provinces in Anatolia, a period which marks the Spartan Hegemony.

464 BC Sparta earthquake

The Sparta earthquake of 464 BC destroyed much of Sparta. Historical sources suggest that the death toll may have been as high as 20,000, although modern scholars suggest that this figure is likely an exaggeration. The earthquake sparked a revolt of the helots, the slave class of Spartan society. Events surrounding this revolt led to an increase in tension between Sparta and their rival Athens and the cancellation of a treaty between them. After the troops of a relief expedition dispatched by conservative Athenians were sent back with cold thanks, Athenian democracy itself fell into the hands of reformers and moved toward a more populist and anti-Spartan policy. Therefore, this earthquake is cited by historical sources as one of the key events that led up to the First Peloponnesian War.

Beginning of animosity with Athens

Sparta's attention was at this time, fully occupied by troubles nearer home; such as the revolt of Tegea (in about 473–471 BC), rendered all the more formidable by the participation of Argos.[47] The most serious, however was the crisis caused by the earthquake which in 464 BC devastated Sparta, costing many lives.[48] In the immediate aftermath, the helots saw an opportunity to rebel. This was followed by the siege of Ithome which the rebel helots had fortified.[49] The pro-Spartan Cimon was successful in getting Athens to send help to put down the rebellion, but this would eventually backfire for the pro-Sparta movement in Athens.[50] The Athenian hoplites that made up the bulk of the force were from the well-to-do section of Athenian society, but were nevertheless openly shocked to discover that the rebels were Greeks like themselves. Sparta began to fear that the Athenian troops might make common cause with the rebels.[51] The Spartans subsequently sent the Athenians home. Providing the official justification that since the initial assault on Ithome had failed, what was now required was a blockade, a task the Spartans did not need Athenian help with. In Athens, this snub resulted in Athens breaking off its alliance with Sparta and allying with its enemy, Argos.[50] Further friction was caused by the consummation of the Attic democracy under Ephialtes and Pericles.[52]

Paul Cartledge hazards that the revolt of helots and perioeci led the Spartans to reorganize their army and integrate the perioeci into the citizen hoplite regiments. Certainly a system where citizens and non-citizens fought together in the same regiments was unusual for Greece.[53] Hans van Wees is, however, unconvinced by the manpower shortage explanation of the Spartans' use of non-citizen hoplites. He agrees that the integration of perioeci and citizens occurred sometime between the Persian and the Peloponnesian Wars but doesn't regard that as a significant stage. The Spartans had been using non-citizens as hoplites well before that and the proportion did not change. He doubts that the Spartans ever subscribed to the citizen only hoplite force ideal, so beloved by writers such as Aristotle.[54]

Peloponnesian Wars

The Peloponnesian Wars were the protracted armed conflicts, waged on sea and land, of the last half of the 5th century BC between the Delian League controlled by Athens and the Peloponnesian League dominated by Sparta over control of the other Greek city-states. The Delian League is often called "the Athenian Empire" by scholars. The Peloponnesian League believed it was defending itself against Athenian aggrandizement.

The war had ethnic overtones that generally but not always applied: the Delian League included populations of Athenians and Ionians while the Peloponnesian League was mainly of Dorians, except that a third power, the Boeotians, had sided tentatively with the Peloponnesian League. They were never fully trusted by the Spartans. Ethnic animosity was fueled by the forced incorporation of small Dorian states into the Delian League, who appealed to Sparta. Motivations, however, were complex, including local politics and considerations of wealth.

In the end Sparta won, but it declined soon enough and was soon embroiled with wars with Boeotia and Persia, until being overcome finally by Macedon.

First Peloponnesian War

When the First Peloponnesian War broke out, Sparta was still preoccupied suppressing the helot revolt,[52] hence its involvement was somewhat desultory.[55] It amounted to little more than isolated expeditions, the most notable of which involved helping to inflict a defeat on the Athenians at the Battle of Tanagra in 457 BC in Boeotia. However they then returned home giving the Athenians an opportunity to defeat the Boeotians at the battle of Oenophyta and so overthrowing Boeotia.[55] When the helot revolt was finally ended, Sparta needed a respite, seeking and gaining a five-year truce with Athens. By contrast, however, Sparta sought a thirty-year peace with Argos to ensure that they could strike Athens unencumbered. Thus Sparta was fully able to exploit the situation when Megara, Boeotia and Euboea revolted, sending an army into Attica. The war ended with Athens deprived of its mainland possessions but keeping its vast Aegean Empire intact. Both of Sparta's Kings were exiled for permitting Athens to regain Euboea and Sparta agreed to a Thirty Year Peace.But the treaty was broken when Sparta warred with Euboea.[56]

Second Peloponnesian War

Within six years, Sparta was proposing to its allies to go to war with Athens in support of the rebellion in Samos. On that occasion Corinth successfully opposed Sparta and they were voted down.[57] When the Peloponnesian War, finally broke out in 431 BC the chief public complaint against Athens was its alliance with Corinth's enemy Korkyra and Athenenian treatment of Potidea. However, according to Thucydides the real cause of the war was Sparta's fear of the growing power of Athens.[58] The Second Peloponnesian War, fought from 431–404 BC would be the longest and costliest war in Greek history.

Archidamian war

Sparta entered with the proclaimed goal of the "liberation of the Greeks" – an aim that required a total defeat of Athens. Their method was to invade Attica in the hope of provoking Athens to give battle. Athens, meanwhile, planned a defensive war. The Athenians would remain in their city, behind their impenetrable walls, and use their naval superiority to harass the Spartan coastline.[59] In 425 BC, a body of Spartans surrendered to the Athenians at Pylos, casting doubt onto their ability to win the war.[60] This was ameliorated by the expedition of Brasidas to Thrace, the one area where Athens possessions were accessible by land, which made possible, the compromise of 421 BC known as the Peace of Nicias. The war between 431 and 421 BC is termed the "Archidamian War" after the Spartan king who invaded Attica when it began, Archidamus II.

Syracusan expedition

The war resumed in 415 BC and lasted until 404 BC. In 415 BC, Athens decided to capture Syracuse, a colony of Dorian Corinth. The arguments advanced in the assembly were that it would be a profitable possession and an enhancement of the empire. They invested a large portion of the state resources in a military expedition, but recalled one of its commanders, Alcibiades, on a trumped-up charge of impiety (some religious statues had been mutilated) for which he faced the death penalty. Escaping in his ship he deserted to Sparta. Having defaulted on the inquiry he was convicted in absentia and sentenced to death.

At first Sparta hesitated to resume military operations. In 414 BC, a combined force of Athenians and Argives raided the Laconian coast, after which Sparta began to take Alcibiades' advice. The success of Sparta and the eventual capture of Athens in 404 BC were aided partly by that advice. He induced Sparta to send Gylippus to conduct the defence of Syracuse, to fortify Decelea in northern Attica, and to adopt a vigorous policy of aiding Athenian allies to revolt.[61] The next year they marched north, fortified Deceleia, cut down all the olive groves, which produced Athens' major cash crop, and denied them the use of the countryside. Athens was now totally dependent on its fleet, then materially superior to the Spartan navy.[60] Spartan generals showed themselves to be not only inexperienced at naval warfare but in the assessment of Forrest, they were often incompetent or brutal or both.[62]

Gylippus did not arrive alone at Syracuse. Collecting a significant force from Sicily and Spartan hoplites serving overseas he took command of the defense. The initial Athenian force under Nicias had sailed boldly into the Great Harbor of Syracuse to set up camp at the foot of the city, which was on a headland. Gylippus collected an international army of pro-Spartan elements from many parts of the eastern Mediterranean on the platform of liberation of Greece from the tyranny of Athens. Ultimately the Athenian force was not large enough to conduct an effective siege. They attempted to wall in the city but were prevented by a counter-wall. A second army under Demosthenes arrived. Finally the Athenian commanders staked everything on a single assault against a weak point on the headland, Epipolae, but were thrown back with great losses. They were about to depart for Athens when an eclipse of the full moon moved the soothsayers to insist they remain for another nine days, just the time needed for the Syracusians to prepare a fleet to block the mouth of the harbor.[63]

Events moved rapidly toward disaster for the Athenians. Attempting to break out of the harbor they were defeated in a naval battle. The admiral, Eurymedon, was killed. Losing confidence in their ability to win, they abandoned the remaining ships and the wounded and attempted to march out by land. The route was blocked at every crossing by Syracusians, who anticipated this move. The Athenian army marched under a rain of missiles. When Nicias inadvertently marched ahead of Demosthenes the Syracusians surrounded the latter and forced a surrender, to which that of Nicias was soon added. Both leaders were executed, despite the protests of Gylippus, who wanted to take them back to Sparta. Several thousand prisoners were penned up in the quarries without the necessities of life or the removal of the dead. After several months the remaining Athenians were ransomed. The failure of the expedition in 413 was a material loss the Athenians could hardly bear, but the war continued for another ten years.

Intervention of the Persians

Spartan shortcomings at sea were by this time manifest to them, especially under the tuteledge of Alcibiades. The lack of funds which could have proved fatal to Spartan naval warfare, was remedied by the intervention of Persia, which supplied large subsidies.[61] In 412 the agents of Tissaphernes, the Great King's governor of such parts of the coast of Asia Minor as he could control, approached Sparta with a deal. The Great King would supply funds for the Spartan fleet if the Spartans would guarantee to the king what he considered ancestral lands; to wit, the coast of Asia Minor with the Ionian cities. An agreement was reached. A Spartan fleet and negotiator was sent to Asia Minor. The negotiator was Alcibiades, now persona non-grata in Sparta because of his new mistress, the wife of King Agis, then away commanding the garrison at Deceleia. After befriending Tissaphernes Alcibiades was secretly offered an honorable return to Athens if he would influence the latter on their behalf. He was a double agent, 411–407. The Spartans received little money or expert advice.[62]

By 408 the Great King had perceived that the agreement with the Spartans was not being implemented. He sent his brother, Cyrus the younger, to relieve Tissaphernes of his command of Lydia. Tissaphernes was pushed aside to the governorship of Caria. Exposed, Alcibiades departed for Athens in 407. In his place Sparta sent an agent of similar capabilities, a friend of King Agis, Lysander, who as "a diplomat and organizer ... was almost flawless, unless we count arrogance, dishonesty, unscrupulousness and brutality as flaws."[64] He and Cyrus got along well. Upgrade of the Spartan fleet proceeded rapidly. In 406 Alcibiades returned as the commander of an Athenian squadron with the intent of destroying the new Spartan fleet, but it was too late. He was defeated by Lysander at the Battle of Notium. The suspicious Athenian government repudiated its arrangement with Alcibiades. He went into exile a second time, to take up residence in a remote villa in the Aegean, now a man without a country.

Lysander's term as navarch then came to an end. He was replaced by Callicratidas but Cyrus now stinted his payments for the Spartan fleet. The funds allocated by the Great King had been used up. On Callicratides' defeat and death at the Battle of Arginusae the Spartans offered peace on generous terms. The Delian League would be left in place. Athens would still be allowed to collect tribute for its defense. The war party at Athens, however, mistrusted Sparta. One of its leaders, Cleophon, addressed the assembly wearing his armor, drunk. He demanded the Spartans withdraw from all cites they then held as a precondition of peace. The assembly rejected the Spartan offer. It undertook a new offensive against Spartan allies in the Aegean.

In the winter of 406/405 those allies met with Cyrus at Ephesus. Together they formulated an appeal to Sparta that Lysander be sent out for a second term. Both Spartan political norms and the Spartan constitution should have prevented his second term, but in the wake of the new Spartan defeat a circumvention was found. Lysander would be the secretary of a nominal navarch, Aracus, with the rank of vice-admiral. Lysander was again entrusted with all the resources needed to maintain and operate the Spartan fleet. Cyrus supplied the funds from his own resources. The Great King now recalled Cyrus to answer for the execution of certain members of the royal family. Cyrus appointed Lysander governor in his place, giving him the right to collect taxes.[65] This trust was justified in 404 BC when Lysander destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami.

Lysander then sailed at his leisure for Athens to impose a blockade. If he encountered a state of the Delian League on his way he gave the Athenian garrison the option of withdrawing to Athens; if they refused, their treatment was harsh. He replaced democracies with pro-Spartan decarchies under a Spartan harmost.

The terms of surrender

After the Battle of Aegospotami the Spartan navy sailed where it pleased unopposed. A fleet of 150 ships entered the Saronic Gulf to impose a blockade on Piraeus. Athens was cut off. In the winter of 404 the Athenians sent a delegation to King Agis at Deceleia proposing to become a Spartan ally if only they would be allowed to keep the walls intact. He sent them on to Sparta. The delegation was turned back on the road by the ephors. After hearing the terms they suggested the Athenians return with better ones.

The Athenians appointed Theramenes to discuss the matter with Lysander, but the latter had made himself unavailable. Theramenes found him, probably on Samos. After a wait of three months he returned to Athens saying that Lysander had delayed him and that he was to negotiate with Sparta directly. A board of nine delegates was appointed to go with Thermenes to Sparta. This time the delegation was allowed to pass.

The disposition of Athens was then debated in the Spartan assembly, which apparently had the power of debate, of veto and of counterproposition. Moreover, the people in assembly were the final power. Corinth and Thebes proposed that Athens be leveled and the land be turned into a pasture for sheep. Agis, supported by Lysander, also recommended the destruction of the city. The assembly refused, stating that they would not destroy a city that had served Greece so well in the past, alluding to Athens' contribution to the defeat of the Persians.

Instead the Athenians were offered terms of unconditional surrender: the long walls must be dismantled, Athens must withdraw from all states of the Delian League and Athenian exiles must be allowed to return. The Athenians could keep their own land. The returning delegates found the population of Athens starving to death. The surrender was accepted in assembly in April, 404, 27 years after the start of the war, with little opposition. A few weeks later Lysander arrived with a Spartan garrison. They began to tear down the walls to the tune of pipes played by young female pipers. Lysander reported to the ephors that "Athens is taken." The ephors complained of his wordiness, stating that "taken" would have been sufficient.[66]

Some modern historians have proposed a less altruistic reason for the Spartans' mercy—the need for a counterweight to Thebes[67]—though Anton Powell sees this as an excess of hindsight. It is doubtful that the Spartans could have predicted that it would be Thebes that would someday pose a serious threat, later defeating the Spartans at the Battle of Leuctra. Lysander's political opponents may have defended Athens not out of gratitude, but out of fear of making Lysander too powerful.[68]

The affair of the thirty

In the spring of 404 BC, the terms of surrender required the Athenians to tear down the long walls between the city and the port of Piraeus. When internal dissent prevented the Athenians from restoring a government Lysander dissolved the democracy and set up a government of 30 oligarchs that would come to be known as the Thirty. These were pro-Spartan men. Originally voted into power by the Assembly with a mandate to codify the laws, they immediately requested the assistance of the Spartan garrison to arrest their enemies.[69] With them they assassinated persons who were pro-democracy and confiscated their property.[70]

The disquiet of Sparta's allies in the Peloponnesian League can be seen in the defiance of Boeotia, Elis and Corinth in offering refuge to those who opposed the rule of the Thirty. Lysander departed Athens to establish decarchies, governing boards of 10 men, elsewhere in the former Athenian Empire, leaving the Spartan garrison under the command of the Thirty. Taking advantage of a general anti-Spartan backlash and a change of regime in Boeotia to an anti-Spartan government, the exiles and non-Athenian supporters (who were promised citizenship) launched an attack from Boeotia on Athens under Thrasybulus and in the Battle of Phyle followed by the Battle of Munichia and the Battle of Piraeus defeated the Athenian supporters of the Thirty with the Spartan garrison regaining partial control of Athens. They set up a decarchy.[71]

Athens was on the brink of civil war. Both sides sent delegates to present their case before King Pausanias. The Thirty were heard first. They complained that Piraeus was being occupied by a Boeotian puppet government. Pausanias immediately appointed Lysander harmost (governor), which required the assent of the ephors, and ordered him to Sparta with his brother, who had been made navarch over 40 ships. They were to put down the rebellion and expel the foreigners.

After the Ten had been fully heard, Pausanias, obtaining the assent of three out of five ephors, went himself to Athens with a force including men from all the allies except the suspect Boeotia and Corinth. He met and superseded Lysander on the road. A battle ensued against Thrasybulus, whose forces killed two Spartan polemarchs but were driven at last into a marsh and trapped there. Pausanias broke off. He set up the board of 15 peace commissioners that had been sent with him by the Spartan assembly and invited both sides to a conference. The final reconciliation restored democracy to Athens. The Thirty held Eleusis, as they had previously massacred the entire population. It was made independent of Athens as a refuge for supporters of the Thirty. A general amnesty was declared. The Spartans ended their occupation.[72]

The former oligarchs repudiated the peace. After failure to raise assistance for their cause among the other states of Greece, they attempted a coup. Faced with the new Athenian state at overwhelming odds they were lured into a conference, seized and executed. Eleusis reverted to Athens.[73] Sparta refused further involvement. Meanwhile, Lysander, who had been recalled to Sparta after his relief by Pausanias, with the assistance of King Agis (the second king) charged Pausanias with being too lenient with the Athenians. Not only was he acquitted by an overwhelming majority of the jurors (except for the supporters of Agis) including all five ephors, but the Spartan government repudiated all the decarchs that had been established by Lysander in former states of the Athenian Empire and ordered the former governments restored.[74]

4th century BC

Spartan supremacy

The two major powers in the eastern Mediterranean in the 5th century BC had been Athens and Sparta. The defeat of Athens by Sparta resulted in Spartan hegemony in the early 4th century BC.

Failed intervention in the Persian Empire

Sparta's close relationship with Cyrus the Younger continued when she gave covert support to his attempt to seize the Persian throne. After Cyrus was killed at the Battle of Cunaxa, Sparta briefly attempted to be conciliatory towards Artaxerxes, the Persian king. In late 401 BC, however, Sparta decided to answer an appeal of several Ionian cities and sent an expedition to Anatolia.[75] Though the war was fought under the banner of Greek liberty, the Spartan defeat at the Battle of Cnidus in 394 BC was widely welcomed by the Greek cities of the region. Though Persian rule meant to the cities of mainland Asia, the payment of tribute, this seems to have been considered a lesser evil than Spartan rule.[75]

The peace of Antalcidas

At the end of 397 BC, Persia had sent a Rhodian agent with gifts to opponents of Sparta on the mainland of Greece. However, these inducements served mainly as encouragement to those who were already resentful of Sparta. In the event, it was Sparta who made the first aggressive move using, as a pretext, Boeotia's support for her ally Locris against Sparta's ally Phocis. An army under Lysander and Pausanias was despatched. As Pausanias was somewhat lukewarm to the whole enterprise, Lysander went on ahead. Having detached Orchomenos from the Boeotian League, Lysander was killed at the Battle of Haliartus. When Pausanias arrived rather than avenge the defeat he simply sought a truce to bury the bodies. For this Pausanias was prosecuted, this time successfully and went into exile.[76]

At the Battle of Coronea, Agesilaus I, the new king of Sparta, had slightly the better of the Boeotians and at Corinth, the Spartans maintained their position, yet they felt it necessary to rid themselves of Persian hostility and if possible use Persian power to strengthen their own position at home: they therefore concluded with Artaxerxes II the humiliating Peace of Antalcidas in 387 BC, by which they surrendered to the Great King of Persia the Greek cities of the Asia Minor coast and of Cyprus, and stipulated for the autonomy of all other Greek cities.[61] Finally, Sparta and Persia were given the right to make war on those who did not respect the terms of the treaty.[77] It was to be a very one sided interpretation of autonomy that Sparta enforced. The Boeotian League was broken up on the one hand while the Spartan dominated Peloponnesian League was excepted. Further, Sparta did not consider that autonomy included the right of a city to choose democracy over Sparta's preferred form of government.[78] In 383 BC an appeal from two cities of Chalkidike and of the King of Macedon gave Sparta a pretext to break up the Chalkidian League headed by Olynthus. After several years of fighting Olynthus was defeated and the cities of the Chalkidike were enrolled into the Peloponnesian League. In hindsight the real beneficiary of this conflict was Philip II of Macedon.[79]

A new civil war

During the Corinthian War Sparta faced a coalition of the leading Greek states: Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos. The alliance was initially backed by Persia, whose lands in Anatolia had been invaded by Sparta and which feared further Spartan expansion into Asia.[80] Sparta achieved a series of land victories, but many of her ships were destroyed at the battle of Cnidus by a Greek-Phoenician mercenary fleet that Persia had provided to Athens. The event severely damaged Sparta's naval power but did not end its aspirations of invading further into Persia, until Conon the Athenian ravaged the Spartan coastline and provoked the old Spartan fear of a helot revolt.[81]

After a few more years of fighting in 387 BC, the Peace of Antalcidas was established, according to which all Greek cities of Ionia would return to Persian control, and Persia's Asian border would be free of the Spartan threat.[81] The effects of the war were to reaffirm Persia's ability to interfere successfully in Greek politics and to affirm Sparta's weakened hegemonic position in the Greek political system.[82]

In 382 BC, Phoebidas, while leading a Spartan army north against Olynthus made a detour to Thebes and seized the Kadmeia, the citadel of Thebes. The leader of the anti-Spartan faction was executed after a show trial, and a narrow clique of pro-Spartan partisans was placed in power in Thebes, and other Boeotian cities. It was a flagrant breach of the Peace of Antalcidas.[83] It was the seizure of the Kadmeia that led to Theban rebellion and hence to the outbreak of the Boeotian War. Sparta started this war with the strategic initiative, however, Sparta failed to achieve its aims.[84] Early on, a botched attack on Piraeus by the Spartan commander Sphodrias undermined Sparta's position by driving Athens into the arms of Thebes.[85] Sparta then met defeat at sea (the Battle of Naxos) and on land (the Battle of Tegyra) and failed to prevent the re-establishment of the Boeotian League and creation of the Second Athenian League.[86]

The peace of Callias

In 371 BC, a fresh peace congress was summoned at Sparta to ratify the Peace of Callias. Again the Thebans refused to renounce their Boeotian hegemony, and the Spartans sent a force under King Cleombrotus in an attempt to enforce Theban acceptance. When the Thebans gave battle at Leuctra, it was more out of brave despair than hope.[87] However, it was Sparta that was defeated and this, along with the death of King Cleombrotus dealt a crushing blow to Spartan military prestige.[88] The result of the battle was to transfer supremacy from Sparta to Thebes.[61]

Decline of the population

As Spartan citizenship was inherited by blood, Sparta now increasingly faced a helot population that vastly outnumbered its citizens. The alarming decline of Spartan citizens was commented on by Aristotle, who viewed it as a sudden event. While some researchers view it as a result of war casualties, it appears that the number of citizens, after a certain point, started declining steadily at a rate of 50% reduction every fifty years regardless of the extent of battles. Most likely, this was the result of steady shifting of wealth among the citizen body, which was simply not as obvious until laws were passed allowing the citizens to give away their land plots.[89]

Facing the Theban hegemony

Sparta never fully recovered from the losses that it suffered at Leuctra in 371 BC and the subsequent helot revolts. Nonetheless, it was able to continue as a regional power for over two centuries. Neither Philip II nor his son Alexander the Great attempted to conquer Sparta itself.

By the winter of late 370 BC, King Agesilaus took the field, not against Thebes, but in an attempt to preserve at least a toehold of influence for Sparta in Arkadia. This backfired when, in response, the Arkadians sent an appeal for help to Boeotia. Boeotia responded by sending a large army, led by Epaminondas, which first marched on Sparta itself and then moved to Messenia where the helots had already rebelled. Epaminondas made that rebellion permanent by fortifying the city of Messene.[90]

The final showdown was in 362 BC, by which time several of Boetia's former allies, such as Mantinea and Elis, had joined Sparta. Athens also fought with Sparta. The resulting Battle of Mantinea was won by Boetia and her allies but in the moment of victory, Epaminondas was killed.[91] In the aftermath of the battle both Sparta's enemies and her allies swore a common peace. Only Sparta itself refused because it would not accept the independence of Messenia.[92]

Facing Macedon

Sparta had neither the men nor the money to recover her lost position, and the continued existence on her borders of an independent Messenia and Arcadia kept her in constant fear for her own safety. She did, indeed, join with Athens and Achaea in 353 BC to prevent Philip II of Macedon passing Thermopylae and entering Phocis, but beyond this, she took no part in the struggle of Greece with the new power which had sprung up on her northern borders.[61] The final showdown saw Philip fighting Athens and Thebes at Chaeronea. Sparta was pinned down at home by Macedonian allies such as Messene and Argos and took no part.[93]

After the Battle of Chaeronea, Philip II of Macedon entered the Peloponnese. Sparta alone refused to join Philip's "Corinthian League" but Philip engineered the transfer of certain border districts to the neighbouring states of Argos, Arcadia and Messenia.[94]

During Alexander's campaigns in the east, the Spartan king, Agis III sent a force to Crete in 333 BC with the aim of securing the island for Sparta.[95] Agis next took command of allied Greek forces against Macedon, gaining early successes, before laying siege to Megalopolis in 331 BC. A large Macedonian army under general Antipater marched to its relief and defeated the Spartan-led force in a pitched battle.[96] More than 5,300 of the Spartans and their allies were killed in battle, and 3,500 of Antipater's troops.[97] Agis, now wounded and unable to stand, ordered his men to leave him behind to face the advancing Macedonian army so that he could buy them time to retreat. On his knees, the Spartan king slew several enemy soldiers before being finally killed by a javelin.[98] Alexander was merciful, and he only forced the Spartans to join the League of Corinth, which they had previously refused to join.[99]

The memory of this defeat was still fresh in Spartan minds when the general revolt against Macedonian rule known as the Lamian War broke out – hence Sparta stayed neutral.[100]

Even during its decline, Sparta never forgot its claims on being the "defender of Hellenism" and its Laconic wit. An anecdote has it that when Philip II sent a message to Sparta saying "If I invade Laconia, I shall turn you out",[101] the Spartans responded with the single, terse reply αἴκα, "if"[102][103][104] (he did[105]).

When Philip created the league of the Greeks on the pretext of unifying Greece against Persia, the Spartans chose not to join—they had no interest in joining a pan-Greek expedition if it was not under Spartan leadership. Thus, upon the conquest of Persia, Alexander the Great sent to Athens 300 suits of Persian armour with the following inscription "Alexander, son of Philip, and all the Greeks except the Spartans, give these offerings taken from the foreigners who live in Asia [emphasis added]".

3rd century BC

During Demetrius Poliorcetes’ campaign to conquer the Peloponnese in 294 BC, the Spartans led by Archidamus IV attempted to resist but were defeated in two battles. Had Demetrius not decided to turn his attention to Macedonia the city would have fallen.[106] In 293 BC, a Spartan force, under Cleonymus, inspired Boeotia to defy Demetrius but Cleonymus soon departed leaving Thebes in the lurch.[107] In 280 BC, a Spartan army, led by King Areus, again marched north, this time under the pretext of saving some sacred land near Delphi from the Aetolians. They somewhat pulled the moral high ground from under themselves, by looting the area. It was at this point that the Aetolians caught them and defeated them.[108]

In 272 BC, Cleonymus of Sparta (who had been displaced as King by Areus[109]), persuaded Pyrrhus to invade the Peloponnese.[110] Pyrrhus laid siege to Sparta confident that he could take the city with ease, however, the Spartans, with even the women taking part in the defence, succeeded in beating off Pyrrhus' attacks.[111] At this point Pyrrhus received an appeal from an opposition Argive faction, for backing against the pro-Gonatas ruler of Argos, and he withdrew from Sparta.[112] In 264 BC, Sparta formed an alliance with Athens and Ptolomeic Egypt (along with a number smaller Greek cities) in an attempt to break free of Macedon.[113] During the resulting Chremonidean War the Spartan King Areus led two expeditions to the Isthmus where Corinth was garrisoned by Macedonia, he was killed in the second.[114] When the Achaean League was expecting an attack from Aetolia, Sparta sent an army under Agis to help defend the Isthmus, but the Spartans were sent home when it seemed that no attack would materialize.[115] In about 244 BC, an Aetolian army raided Laconia, carrying off, (it was said) 50,000 captives,[61] although that is likely to be an exaggeration.[116] Grainger has suggested that this raid was part of Aetolia's project to build a coalition of Peloponnesian cities. Though Aetolia was primarily concerned with confining Achaea, because the cities concerned were hostile to Sparta, Aetolia needed to demonstrate her anti-Spartan credentials.[117]

During the 3rd century BC, a social crisis slowly emerged: wealth had become concentrated amongst about 100 families[118] and the number of equals (who had always formed the backbone of the Spartan army) had fallen to 700 (less than a tenth of its 9000 strong highpoint in the 7th century BC).[118] Agis IV was the first Spartan king to attempt reform. His program combined debt cancellation and land reform. Opposition from King Leonidas was removed when he was deposed on somewhat dubious grounds. However, his opponents exploited a period when Agis IV was absent from Sparta and, on his return he was subjected to a travesty of a trial.[119]

The next attempt at reform came from Cleomenes III, the son of King Leonidas. In 229 BC, Cleomenes led an attack on Megalopolis, hence provoking war with Achaea. Aratus, who led the Achaean League forces, adopted a very cautious strategy, despite having 20,000 to Cleomenes 5000 men. Cleomenes was faced with obstruction from the Ephors which probably reflected a general lack of enthusiasm amongst the citizens of Sparta.[120] Nonetheless he succeeded in defeating Aratus.[121] With this success behind him he left the citizen troops in the field and with the mercenaries, marched on Sparta to stage a coup d'état. The ephorate was abolished – indeed four out of five of them had been killed during Cleomenes' seizure of power.[122] Land was redistributed enabling a widening of the citizen body.[122] Debts were cancelled. Cleomenes gave to Sphaerus, his stoic advisor, the task of restoring the old severe training and simple life. Historian Peter Green comments that giving such a responsibility to a non-Spartan was a telling indication of the extent that Sparta had lost her Lycurgian traditions.[122] These reforms excited hostility amongst the wealthy of the Peloponnese who feared social revolution. For others, especially among the poor, Cleomenes inspired hope. This hope was quickly dashed when Cleomenes started taking cities and it became obvious that social reform outside Sparta was the last thing on his mind.[123]

Cleomenes' reforms had as their aim, the restoration of Spartan power. Initially Cleomenes was successful, taking cities that had until then been part of the Achaean League[124] and winning the financial backing of Egypt.[125] However Aratus, the leader of the Achaean League, decided to ally with Achaea's enemy, Macedonia. With Egypt deciding to cut financial aid Cleomenes decided to risk all on one battle.[126] In the resulting Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC, Cleomenes was defeated by the Achaeans and Macedonia. Antigonus III Doson, the king of Macedon ceremonially entered Sparta with his army, something Sparta had never endured before. The ephors were restored, while the kingship was suspended.[127]

At the beginning of the Social War in 220 BC, envoys from Achaea unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Sparta to take the field against Aetolia. Aetolian envoys were at first equally unsuccessful but their presence was used as a pretext by Spartan royalists who staged a coup d'état that restored the dual kingship. Sparta then immediately entered the war on the side of Aetolia.[128]

Roman Sparta

The sources on Nabis, who took power in 207 BC, are so uniformly hostile that it is impossible today to judge the truth of the accusation against him – that his reforms were undertaken only to serve his own interests.[129] Certainly his reforms went far deeper than those of Cleomenes who had liberated 6000 helots merely as an emergency measure.[130] The Encyclopædia Britannica states:

Nabis...if we may trust the accounts given by Polybius and Livy, was little better than a bandit chieftain, holding Sparta by means of extreme cruelty and oppression, and using mercenary troops to a large extent in his wars.[131]

The historian W.G. Forest is willing to take these accusations at face value including that he murdered his ward, and participated in state sponsored piracy and brigandage – but not the self-interested motives ascribed to him. He sees him as a ruthless version of Cleomenes, sincerely attempting to solve Sparta's social crisis.[132] He initiated the building of Sparta's first walls which extended to some 6 miles.[133]

It was this point that Achaea switched her alliance with Macedon to support Rome. As Achaea was Sparta's main rival, Nabis leaned towards Macedonia. It was getting increasingly difficult for Macedonia to hold Argos, so Philip V of Macedon decided to give Argos to Sparta which increased tension with the Achaean League. Nonetheless, he was careful not to violate the letter of his alliance with Rome.[132] After the conclusion of the wars with Philip V, Sparta's control of Argos contradicted the official Roman policy of freedom to the Greeks and Titus Quinctius Flamininus organized a large army with which he invaded Laconia and laid siege to Sparta.[134] Nabis was forced to capitulate, evacuating all his possessions outside Laconia, surrendering the Laconian seaports and his navy, and paying an indemnity of 500 talents, while freed slaves were returned to their former masters.[134][135]

Though the territory under his control now consisted only of the city of Sparta and its immediate environs, Nabis still hoped to regain his former power. In 192 BC, seeing that the Romans and their Achaean allies were distracted by the imminent war with King Antiochus III of Syria and the Aetolian League, Nabis attempted to recapture the harbor city of Gythium and the Laconian coastline.[136] Initially, he was successful, capturing Gythium and defeating the Achaean League in a minor naval battle.[136] Soon after, however, his army was routed by the Achaean general Philopoemen and shut up within the walls of Sparta. After ravaging the surrounding countryside, Philopoemen returned home.[136]

Within a few months, Nabis appealed to the Aetolian League to send troops so that he might protect his territory against the Romans and the Achaean League.[136] The Aetolians responded by sending an army to Sparta.[137] Once there, however, the Aetolians betrayed Nabis, assassinating him while he was drilling his army outside the city.[137] The Aetolians then attempted to take control of the city, but were prevented from doing so by an uprising of the citizens.[137] The Achaeans, seeking to take advantage of the ensuing chaos, dispatched Philopoemen to Sparta with a large army. Once there, he compelled the Spartans to join the Achaean League ending their independence.[138]

Sparta played no active part in the Achaean War in 146 BC when the Achaean League was defeated by the Roman general Lucius Mummius. Subsequently, Sparta become a free city in the Roman sense, some of the institutions of Lycurgus were restored[139] and the city became a tourist attraction for the Roman elite who came to observe exotic Spartan customs.[n 1] The former Perioecic communities were not restored to Sparta and some of them were organized as the "League of Free Laconians".

After 146 BC, sources for Spartan history are somewhat fragmentary.[142] Pliny describes its freedom as being empty, though Chrimes argues that while this may be true in the area of external relations, Sparta retained a high level of autonomy in internal matters.[143]

A passage in Suetonius reveals that the Spartans were clients of the powerful patrician clan of the Claudii. Octavians's wife Livia was a member of the Claudii which might explain why Sparta was one of the few Greek cities that backed Octavian first in the war against Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC then in the war against Mark Antony in 30 BC.[144]

During the late 1st century BC and much of the 1st century AD Sparta was dominated by the powerful family of the Euryclids which acted something like a "client-dynasty" for the Romans.[145] After the fall of the Euryclids from grace during the reign of Nero the city was ruled by republican institutions and civic life seems to have flourished. During the 2nd century AD a 12 kilometers long aqueduct was built.

The Romans fielded Spartan auxiliary troops in their wars against the Parthians under the emperors Lucius Verus and Caracalla.[146] It is likely that the Romans wished to use the legend of Spartan prowess.[146] After an economic decline in the 3rd century, urban prosperity returned in the 4th century and Sparta even became a minor center of high studies as attested in some of the letters of Libanius.

Post-classical periods

Sparta during the Migration Period

In 396 AD, Alaric sacked Sparta and, though it was rebuilt, the revived city was much smaller than before.[147] The city was finally abandoned during this period when many of the population centers of the Peloponnese were raided by an Avaro-Slav army. Some settlement by Proto-Slavic tribes occurred around this time.[148] The scale of the Slavic incursions and settlement in the later 6th and especially in the 7th century remain a matter of dispute. The Slavs occupied most of the Peloponnese, as evidenced by Slavic toponyms, with the exception of the eastern coast, which remained in Byzantine hands. The latter was included in the thema of Hellas, established by Justinian II ca. 690.[149][150]

Under Nikephoros I, following a Slavic revolt and attack on Patras, a determined Hellenization process was carried out. According to the (not always reliable) Chronicle of Monemvasia, in 805 the Byzantine governor of Corinth went to war with the Slavs, exterminated them, and allowed the original inhabitants to claim their own lands. They regained control of the city of Patras and the peninsula was re-settled with Greeks.[151] Many Slavs were transported to Asia Minor, and many Asian, Sicilian and Calabrian Greeks were resettled in the Peloponnese. The entire peninsula was formed into the new thema of Peloponnesos, with its capital at Corinth. There was also continuity of the Peloponnesian Greek population.[152] With re-Hellenization, the Slavs likely became a minority among the Greeks, although the historian J.V.A. Fine considers it is unlikely that a large number of people could have easily been transplanted into Greece in the 9th century; this suggests that many Greeks had remained in the territory and continued to speak Greek throughout the period of Slavic occupation.[153] By the end of the 9th century, the Peloponnese was culturally and administratively Greek again,[154] with the exception of a few small Slavic tribes in the mountains such as the Melingoi and Ezeritai.

According to Byzantine sources, the Mani Peninsula in southern Laconian remained pagan until well into the 10th century. In his De administrando imperio, Emperor Constantine Porphyrogennetos also claims that the Maniots retained autonomy during the Slavic invasion, and that they descend from the ancient Greeks. Doric-speaking populations survive today in Tsakonia. During its Middle Ages, the political and cultural center of Laconia shifted to the nearby settlement of Mystras.

Sparta of the Late Middle Ages

On their arrival in the Morea, the Frankish Crusaders found a fortified city named Lacedaemonia (Sparta) occupying part of the site of ancient Sparta, and this continued to exist, though greatly depopulated, even after the Prince of Achaea William II Villehardouin had in 1249 founded the fortress and city of Mystras, on a spur of Taygetus (some 3 miles northwest of Sparta).[131]

This passed shortly afterwards into the hands of the Byzantines and became the centre of the Despotate of the Morea, until the Ottoman Turks under Mehmed II captured it in 1460. In 1687 it came into the possession of the Venetians, from whom it was wrested again in 1715 by the Turks. Thus for nearly six centuries it was Mystras and not Sparta which formed the center and focus of Laconian history.[131]

In 1777, following the Orlov events, some inhabitants of Sparta bearing the name "Karagiannakos" (Greek: Καραγιαννάκος) migrated to Koldere, near Magnesia (ad Sipylum).[155]

The Mani Peninsula region of Laconia retained some measure of autonomy during the Ottoman period, and played a significant role in the Greek War of Independence.

Modern Sparta

Until modern times, the site of ancient Sparta was occupied by a small town of a few thousand people who lived amongst the ruins, in the shadow of Mystras, a more important medieval Greek settlement nearby. The Palaiologos family (the last Byzantine Greek imperial dynasty) also lived in Mystras. In 1834, after the Greek War of Independence, King Otto of Greece decreed that the town was to be expanded into a city.

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 1

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus 15

- ↑ Cartledge 2002, p. 28

- ↑ Herodotus 1.56.3

- ↑ Tod 1911, p. 609.

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, Sparta and Laconia. A regional history 1300 to 362 BC. 2nd Edition, p. 65.

- ↑ Chadwick, J., "Who were the Dorians", La Parola del Pasato 31, pp. 103–117.

- ↑ W. G. Forrest, p. 25.

- ↑ W. G. Forrest, A History of Sparta, pp. 26–30.

- 1 2 W. G. Forrest, A History of Sparta, p. 31.

- ↑ Ehrenberg 2002, p. 36

- ↑ Ehrenberg 2002, p. 33

- ↑ W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p55

- 1 2 3 Tod 1911, p. 610.

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, The Spartans pp58-9

- ↑ The Spartan Army J. F. Lazenby pp. 63–67

- ↑ The Spartan Army J. F. Lazenby p. 68

- 1 2 Ehrenberg 2002, p. 31

- ↑ W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p. 32

- ↑ https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Paus.+3.2.6&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0160 Pausanias 2.3.6

- ↑ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p32

- ↑ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p40

- 1 2 "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 42

- ↑ Herodotus ( 1.82),

- ↑ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, pp. 51–2

- ↑ "A Historical Commentary on Thucydides"—David Cartwright, p. 176

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley p61

- ↑ W G Forrest, A History of Sparta pp. 76–77

- 1 2 W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p. 79

- ↑ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 57

- ↑ "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 58

- ↑ W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p. 86

- ↑ W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p. 87

- ↑ W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p. 89

- ↑ Persian Fire: The First World Empire, Battle for the West p258

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp171-173

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley p. 173

- ↑ Green 1998, p. 10

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp181-184

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp. 184

- ↑ Britannica ed. 2006, "Sparta"

- ↑ History of Greece, from the beginnings to the Byzantine Era. Hermann Bengston, trans Edmund Bloedow p104

- ↑ History of Greece, from the beginnings to the Byzantine Era. Hermann Bengston, trans Edmund Bloedow p105

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp189

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp. 228–9

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp230-1

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750–323 BC. Terry Buckley pp. 232–5

- ↑ Tod 1911, p. 611.

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750–323 BC. Terry Buckley pp236

- 1 2 Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp. 236–7

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, The Spartans pp. 140–141

- 1 2 Buckley 2010, p. 237

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, The Spartans p. 142

- ↑ Hans van Wees, Greek Warfare, Myths and Realities pp. 83–4

- 1 2 Forrest 1968, pp. 106–107

- ↑ Buckley 2010, pp. 239–240

- ↑ Buckley 2010, p. 309

- ↑ Buckley 2010, pp. 307–311

- ↑ Buckley 2010, pp. 354–355

- 1 2 Forrest 1968, pp. 111–112

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tod 1911, p. 612.

- 1 2 Forrest 1968, p. 119

- ↑ Thucydides, Peloponnesian War, 7.22–23.

- ↑ Forrest 1968, p. 120

- ↑ The relationship with the Persians is described in Kagan, Donald (2003). The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking (The Penguin Group). pp. 468–471. ISBN 9780670032112..

- ↑ The previous four paragraphs rely heavily on Lazenby, John Francis (2004). The Peloponnesian War: a military study. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 246–250. ISBN 9780415326155.

- ↑ Forrest 1968, p. 121

- ↑ Powell, Anton (2006), "Why did Sparta not destroy Athens in 404, or 403 BC?", in Hodkinson, Stephen; Powell, Anton (eds.), Sparta & War, Proceedings, International Sparta Seminar, 5th: 2004: Rennes, France, Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, p. 302

- ↑ Dillon, Matthew; Garland, Lynda (2010). Ancient Greece: Social and Historical Documents from Archaic Times to the Death of Alexander the Great. Routledge Sourcebooks for the Ancient World (3rd ed.). Oxford: Routledge. p. 446.

- ↑ Bauer, S. Wise (2007). The history of the ancient world: from the earliest accounts to the fall of Rome. New York [u.a.]: Norton. p. 553. ISBN 9780393059748.

- ↑ Buck 1998, pp. 67–80

- ↑ Buck 1998, pp. 81–88

- ↑ Thirlwall, Connop (1855). The history of Greece. Vol. IV (New ed.). London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. p. 214.

- ↑ Andrewes, A (1978), "Spartan Imperialism", in Garnsey, Peter; Whittaker, C R (eds.), Imperialism in the ancient world: the Cambridge University research seminar in ancient history, Cambridge Classical Studies, Cambridge [Eng.]; New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 100

- 1 2 Agesilaos, P Cartledge p191

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge p358-9

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge p. 370

- ↑ Agesilaos , P Cartledge p370

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge pp. 373–4

- ↑ "Dictionary of Ancient&Medieval Warfare"—Matthew Bennett, p. 86

- 1 2 "The Oxford Illustrated History of Greece and the Hellenistic World" p. 141, John Boardman, Jasper Griffin, Oswyn Murray

- ↑ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 556–9

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge p. 374

- ↑ Agesilaos' Boiotian Campaigns and the Theban Stockade, Mark Munn, Classical Antiquity 1987 April p. 106

- ↑ Aspects of Greek History 750-323BC. Terry Buckley pp446

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge pp.376–7

- ↑ History of Greece, G Grote vol9 p. 395

- ↑ HISTORY OF GREECE, G Grote vol9 p402

- ↑ L. G. Pechatnova, A History of Sparta (Archaic and Classic Periods)

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge p384-5

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge p391

- ↑ Agesilaos, P Cartledge p. 392

- ↑ Alexander the Great Failure, John D. Grainger, pp61-2

- ↑ The Spartan Army J. F. Lazenby p. 169

- ↑ Agis III

- ↑ Agis III, by E. Badian © 1967 – Jstor

- ↑ Diodorus, World History

- ↑ Diodorus, World History, 17.62.1–63.4;tr. C.B. Welles

- ↑ Alexander the Great and his time By Agnes Savill Page 44 ISBN 0-88029-591-0

- ↑ Peter Green, Alexander to Actium p. 10

- ↑ Plutarch; W.C.Helmbold. "De Garrulitate". Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

ἂν ἐμβάλω εἰς τὴν Λακωνικήν, ἀναστάτους ὑμᾶς ποιήσω

- ↑ Davies 2010, p. 133.

- ↑ Plutarch 1874, De garrulitate, 17.

- ↑ Plutarch 1891, De garrulitate, 17; in Greek.

- ↑ Cartledge, Paul (2002). Sparta and Lakonia : a regional history, 1300-362 B.C. (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 273. ISBN 0-415-26276-3.

Philip laid Lakonia waste as far south as Gytheion and formally deprived Sparta of Dentheliatis (and apparently the territory on the Messenian Gulf as far as the Little Pamisos river), Belminatis, the territory of Karyai and the east Parnon foreland.

- ↑ Peter Green, Alexander to Actium p125

- ↑ The Wars of Alexander's Successors 323 – 281 BC: Commanders and Campaigns v. 1 p. 193, Bob Bennett, Mike Roberts

- ↑ John D Grainger, The League of the Aetolians p. 96

- ↑ The Spartan Army, J. F. Lazenby p172

- ↑ Peter Green, Alexander to Actium p. 144

- ↑ Historians History of the World, Editor: Henry Smith Williams vol 4 pp. 512–13

- ↑ W. W. Tarn, Antigonas Gonatas, p. 272.

- ↑ Janice Gabbert, Antigontas II Gontas, p. 46.

- ↑ Janice Gabbert, Antigontas II Gontas, pp. 47–8.

- ↑ John D. Grainger, The League of the Aetolians, p. 152.

- ↑ John D Grainger, The League of the Aetolians p162

- ↑ John D. Grainger, The League of the Aetolians, pp. 162–4.

- 1 2 Peter Green, Alexander to Actium p250

- ↑ Peter Green, Alexander to Actium p. 253

- ↑ Ancient Sparta, K M T Chrimes, 1949, p. 9

- ↑ Historians History of the World, Editor: Henry Smith Williams vol 4 p523

- 1 2 3 Peter Green, Alexander to Actium p257

- ↑ Peter Green, Alexander to Actium pp. 259–60

- ↑ Historians History of the World, Editor: Henry Smith Williams vol 4 pp. 523–4

- ↑ Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age: A Short History, Peter Green p87

- ↑ Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age: A Short History, Peter Green p88

- ↑ Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age: A Short History, Peter Green p89

- ↑ John D Grainger, The League of the Aetolians

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, The Spartans p234

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, The Spartans p. 235

- 1 2 3 Tod 1911, p. 613.

- 1 2 W G Forrest, A History of Sparta p. 149

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, The Spartan s p. 236

- 1 2 "Spartans, a new history", Nigel Kennell, 2010, p. 179

- ↑ Livy xxxiv. 33–43

- 1 2 3 4 Smith =

- 1 2 3 Livy, 35.35

- ↑ Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, p. 77

- ↑ Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, p. 82

- ↑ Cicero (1918). "II.34". In Pohlenz, M. (ed.). Tusculanae Disputationes (in Latin). Leipzig: Teubner. At the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Michell, Humfrey (1964). Sparta. Cambridge University Press. p. 175.

- ↑ Ancient Sparta, K M T Chrimes, 1949, p. 52

- ↑ Ancient Sparta, K M T Chrimes, 1949, p53

- ↑ Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, p. 87

- ↑ Cartledge and Spawforth, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta:A tale of two Cities, p. 94

- 1 2 The Spartan Army J. F. Lazenby p. 204

- ↑ Spartans: A New History (Ancient Cultures) [Paperback] Nigel M. Kennell p193-4

- ↑ Spartans: A New History (Ancient Cultures) [Paperback] Nigel M. Kennell p194

- ↑ Kazhdan (1991), pp. 911, 1620

- ↑ Obolensky (1971), pp. 54–55, 75

- ↑ Fine (1983), pp. 80, 82

- ↑ Fine (1983), p. 61

- ↑ Fine (1983), p. 64

- ↑ Fine (1983), p. 79

- ↑ H καταγωγή των Κολτεριωτών της Σμύρνης – Του Μωυσιάδη Παναγιώτη e-ptolemeos.gr (in Greek)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Tod, Marcus Niebuhr (1911). "Sparta". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 609–614. See pp. 610–613.

Bibliography

- Buck, Robert J (1998). Thrasybulus and the Athenian democracy: the life of an Athenian statesman. Historia, Heft 120. Stuttgart: F. Steiner.

- Buckley, T. (2010). Aspects of Greek history 750–323 BC: a source-based approach (Second ed.). Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-54977-6.

- Davies, Norman (30 September 2010). Europe: A History. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-9179-2.

- Ehrenberg, Victor (2002) [1973], From Solon to Socrates: Greek History and Civilisation between the 6th and 5th centuries BC (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-04024-2

- Forrest, W.G. (1968). A History of Sparta 950-192 B.C. New York; London: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-00481-3.

- Cartledge, Paul. Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

- Green, Peter (1998), The Greco-Persian Wars (2nd ed.), Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-20313-5

- Pechatnova, Larisa (2001). A History of Sparta (Archaic and Classic Periods). Гуманитарная Академия. ISBN 5-93762-008-9.

- Plutarch (1874), Plutarch's Morals, Translated from the Greek by several hands. Corrected and revised by. William W. Goodwin, PH. D., Boston, Cambridge

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Plutarch (1891), Bernardakis, Gregorius N. (ed.), Moralia, Plutarch (in Greek), Leipzig: Teubner