| Matanikau Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

U.S. Marines cross the Matanikau River on a raft ferry in November 1942 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alexander Vandegrift Merritt A. Edson |

Harukichi Hyakutake Tadashi Sumiyoshi Nomasu Nakaguma † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

4,000[1] | 1,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 71 killed[3] | 400 killed[4] | ||||||

9°26′6.33″S 159°57′4.46″E / 9.4350917°S 159.9512389°E The Matanikau Offensive, from 1–4 November 1942, sometimes referred to as the Fourth Battle of the Matanikau, was an engagement between United States (U.S.) Marine and Army and Imperial Japanese Army forces around the Matanikau River and Point Cruz area on Guadalcanal during the Guadalcanal campaign of World War II. The action was one of the last of a series of engagements between U.S. and Japanese forces near the Matanikau River during the campaign.

In the engagement, seven battalions of U.S. Marine and Army troops under the overall command of Alexander Vandegrift and tactical command of Merritt A. Edson, following up on the U.S. victory in the Battle for Henderson Field, crossed the Matanikau River and attacked Japanese Army units between the river and Point Cruz, on the northern Guadalcanal coast. The area was defended by the Japanese Army's 4th Infantry Regiment under Nomasu Nakaguma along with various other support troops, under the overall command of Harukichi Hyakutake. After inflicting heavy casualties on the Japanese defenders, U.S. forces halted the offensive and temporarily withdrew because of a perceived threat from Japanese forces elsewhere in the Guadalcanal area.

Background

Guadalcanal campaign

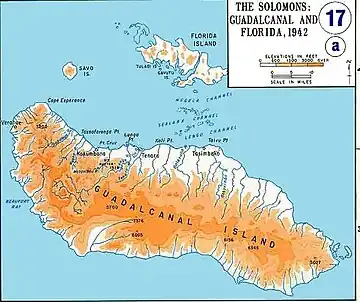

On 7 August 1942, Allied forces (primarily U.S.) landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and to secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of isolating the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.[5]

Taking the Japanese by surprise, by nightfall on 8 August the 11,000 Allied troops, under the command of Lieutenant General Alexander Vandegrift and mainly consisting of United States Marine Corps units, had secured Tulagi and nearby small islands, as well as an airfield under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. The airfield was later named Henderson Field by Allied forces. The Allied aircraft that subsequently operated out of the airfield became known as the "Cactus Air Force" (CAF) after the Allied codename for Guadalcanal. To protect the airfield, the U.S. Marines established a perimeter defense around Lunga Point.[6]

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army's 17th Army, a corps-sized command based at Rabaul and under the command of Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake, with the task of retaking Guadalcanal from Allied forces. Beginning on 19 August, various units of the 17th Army began to arrive on Guadalcanal with the goal of driving Allied forces from the island.[7]

Because of the threat by CAF aircraft based at Henderson Field, the Japanese were unable to use large, slow transport ships to deliver troops and supplies to the island. Instead, the Japanese used warships based at Rabaul and the Shortland Islands to carry their forces to Guadalcanal. The Japanese warships, mainly light cruisers or destroyers from the Eighth Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, were usually able to make the round trip down "The Slot" to Guadalcanal and back in a single night, thereby minimizing their exposure to CAF air attack. Delivering the troops in this manner, however, prevented most of the soldiers' heavy equipment and supplies, such as heavy artillery, vehicles, and much food and ammunition, from being carried to Guadalcanal with them. These high speed warship runs to Guadalcanal occurred throughout the campaign and were later called the "Tokyo Express" by Allied forces and "Rat Transportation" by the Japanese.[8]

The first Japanese attempt to recapture Henderson Field failed when a 917-man force was defeated on 21 August in the Battle of the Tenaru. The next attempt took place from 12 to 14 September, with the 6,000 soldiers under the command of Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi being defeated in the Battle of Edson's Ridge. After their defeat at Edson's Ridge, Kawaguchi and the surviving Japanese troops regrouped west of the Matanikau River on Guadalcanal.[9]

As the Japanese regrouped, the U.S. forces concentrated on shoring up and strengthening their Lunga defenses. On 18 September, an Allied naval convoy delivered 4,157 men from the U.S. 7th Marine Regiment to Guadalcanal. These reinforcements allowed Vandegrift, beginning on 19 September, to establish an unbroken line of defense completely around the Lunga perimeter.[10]

General Vandegrift and his staff were aware that Kawaguchi's troops had retreated to the area west of the Matanikau and that numerous groups of Japanese stragglers were scattered throughout the area between the Lunga Perimeter and the Matanikau River. Vandegrift therefore decided to conduct a series of small unit operations around the Matanikau valley.[11]

The first U.S. Marine operation against Japanese forces west of the Matanikau, conducted between 23 September and 27 September 1942 by elements of three U.S. Marine battalions, was repulsed by Kawaguchi's troops under Colonel Akinosuke Oka's local command. In the second action, between 6 October and October, a larger force of U.S. Marines successfully crossed the Matanikau River, attacked newly landed Japanese forces from the 2nd (Sendai) Infantry Division under the command of generals Masao Maruyama and Yumio Nasu and inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese 4th Infantry Regiment. The second action forced the Japanese to retreat from their positions east of the Matanikau.[13]

In the meantime, Major General Millard F. Harmon, commander of United States Army forces in the South Pacific, convinced Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, commander of Allied forces in the South Pacific Area, that U.S. Marine forces on Guadalcanal needed to be reinforced immediately if the Allies were to successfully defend the island from the anticipated Japanese offensive. Thus on 13 October, a naval convoy delivered the 2,837-strong 164th U.S. Infantry Regiment, a North Dakota Army National Guard formation from the U.S. Army's Americal Division, to Guadalcanal.[14]

Battle for Henderson Field

Between 1 October and 17 October, the Japanese delivered 15,000 troops to Guadalcanal, giving Hyakutake 20,000 total troops to employ for his planned offensive. Because of the loss of their positions on the east side of the Matanikau, the Japanese decided that an attack on the U.S. defenses along the coast would be prohibitively difficult. Therefore, Hyakutake decided that the main thrust of his planned attack would be from south of Henderson Field. His 2nd Division (augmented by troops from the 38th Infantry Division), under Lieutenant General Masao Maruyama and comprising 7,000 soldiers in three infantry regiments of three battalions each was ordered to march through the jungle and attack the American defences from the south near the east bank of the Lunga River.[15] To distract the Americans from the planned attack from the south, Hyakutake's heavy artillery plus five battalions of infantry (about 2,900 men) from the 4th and 124th Infantry Regiments under the overall command of Major General Tadashi Sumiyoshi were to attack the American defenses from the west along the coastal corridor.[16]

Sumiyoshi's forces, including two battalions of the 4th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Nomasu Nakaguma, launched attacks on the U.S. Marine defenses at the mouth of the Matanikau on the evening of 23 October. U.S. Marine artillery, cannon, and small arms fire repulsed the assaults and killed many of the attacking Japanese soldiers while suffering only light casualties.[17]

Beginning on 24 October and continuing over two consecutive nights, Maruyama's forces conducted numerous, unsuccessful frontal assaults on the southern portion of the U.S. Lunga perimeter. More than 1,500 of Maruyama's troops were killed in the attacks while the Americans lost about 60 killed.[18]

Further Japanese attacks near the Matanikau on 26 October by Oka's 124th Infantry Regiment were also repulsed with heavy losses for the Japanese. Thus, at 08:00 on 26 October, Hyakutake called off any further attacks and ordered his forces to retreat. About half of Maruyama's survivors were ordered to retreat back to the area west of the Matanikau River while the rest, the 230th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Toshinari Shoji, was told to head for Koli Point, east of the Lunga perimeter. The 4th Infantry Regiment retreated back to positions west of the Matanikau and around the Point Cruz area while the 124th Infantry Regiment took up positions on the slopes of Mount Austen in the upper Matanikau Valley.[19]

In order to exploit the recent victory, Vandegrift planned another offensive west of the Matanikau which would have two objectives: to drive the Japanese beyond artillery range of Henderson Field and to cut off the retreat of Maruyama's men towards the village of Kokumbona, location of the 17th Army's headquarters. For the offensive, Vandegrift committed the three battalions of the 5th Marine Regiment, commanded by Colonel Merritt Edson, plus the augmented 3rd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment (called the Whaling Group) commanded by Colonel William Whaling. Two battalions of the 2nd Marine Regiment would be in reserve. The offensive was supported by artillery from the 11th Marine Regiment and the 164th Infantry Regiment, CAF aircraft, and gunfire from U.S. Navy warships. Edson was placed in tactical command of the operation.[21]

Defending the Matanikau area for the Japanese were the 4th and 124th Infantry Regiments. Nakaguma's 4th Infantry defended the Matanikau from the shore to about 1,000 yards (914 m) inland while Oka's 124th Infantry extended the line further inland along the river. Both regiments, which on paper consisted of six battalions, were severely understrength because of battle damage, tropical disease, and malnutrition. In fact, Oka described his command as at only "half strength."[22]

Action

Between 01:00 and 06:00 on 1 November, U.S. Marine engineers constructed three footbridges across the Matanikau. At 06:30, nine Marine and U.S. Army artillery batteries (about 36 guns) and U.S. warships San Francisco, Helena, and Sterett opened fire on the west bank of the Matanikau, and U.S. aircraft, including 19 B-17 heavy bombers, dropped bombs in the same area. At the same time, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines (1/5) crossed the Matanikau at its mouth while the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines (2/5) and the Whaling Group crossed the river further inland. Facing the Marines was the Japanese 2nd Battalion, 4th Infantry under Major Masao Tamura.[23]

The 2/5 and the Whaling Group encountered very little resistance and reached and occupied several ridges south of Point Cruz by early afternoon. Along the coast near Point Cruz, however, the 7th Company from Tamura's battalion fiercely resisted the U.S. advance. In several hours of fighting, Company C, 1/5 suffered heavy casualties, including the loss of three officers, and was driven back toward the Matanikau by Tamura's troops. Assisted by another company from 1/5 and later by two companies from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines (3/5), plus determined resistance by Marine Corporal Anthony Casamento, among others, the Americans were successful in stopping the retreat.[24]

Reviewing the situation at the end of the day, Edson, along with Colonel Gerald Thomas and Lieutenant Colonel Merrill Twining from Vandegrift's staff, decided to try to encircle the Japanese defenders around Point Cruz. They ordered 1/5 and 3/5 to continue to press the Japanese along the coast the next day while 2/5 wheeled north to envelop their adversaries west and south of Point Cruz. Tamura's battalion had taken heavy losses in the day's fighting, with Tamura's 7th and 5th Companies being left with only 10 and 15 uninjured soldiers respectively.[25]

Fearing that the U.S. troops were on the verge of breaking through their defenses, Hyakutake's 17th Army headquarters hurriedly sent whatever troops could be found on-hand to bolster the 4th Infantry's defensive efforts. The troops included the 2d Anti-Tank Gun Battalion with 12 guns and the 39th Field Road Construction Unit. These two units took position in pre-prepared fighting emplacements around the south and west of Point Cruz.[26]

On the morning of 2 November, with the Whaling Group covering their flank, the men of 2/5 marched north and reached the coast west of Point Cruz, completing the encirclement of the Japanese defenders. The Japanese defenses were centered in a draw between a coastal trail and a beach just west of Point Cruz and included coral, earth, and log bunkers as well as caves and foxholes. U.S. artillery bombarded the Japanese positions throughout the day on 2 November, causing an unknown number of casualties to the Japanese defenders.[27]

Later in the day, Company I of 2/5 conducted a frontal assault with fixed bayonets on the northern portion of the Japanese defenses, overrunning and killing the Japanese defenders. At the same time, two battalions from 2nd Marine Regiment, now committed to the offensive, advanced past the Point Cruz area.[28]

At 06:30 on 3 November, some Japanese troops attempted to break out of the pocket but were beaten back by the Marines. Between 08:00 and 12:00, five Marine companies from 2/5 and 3/5, using small arms, mortars, demolition charges, and direct and indirect artillery fire, completed the destruction of the Japanese pocket near Point Cruz. Marine participant Richard A. Nash described the battle:

A jeep wheeled up towing a 37-mm anti-tank gun and Captain Andrews of D Company put a crew of men to setting the thing up to fire into the palm grove. Then I heard it—just before the gun began firing—a weird wailing and moaning, almost a religious chant ... coming from the trapped Japanese soldiers. Then the gun fired canister shot into them, again and again, and after a while the chanting stopped and the firing stopped and for a moment it was all-quiet. Some of us went among the palm trees to look, and there, row on row, were the torn and shattered bodies of perhaps 300 young Japanese soldiers. There were no survivors.[29]

The Marines captured 12 37mm anti-tank guns, one 70 mm field artillery piece, and 34 machine guns and counted the dead bodies of 239 Japanese soldiers, including 28 officers.[30]

At the same time, the 2nd Marines with the Whaling Group continued to push along the coast, reaching a point 3,500 yards (3,200 m) west of Point Cruz by nightfall. The only Japanese troops left in the area to oppose the Marines' advance were the remaining 500 soldiers of the 4th Infantry augmented by a few frail survivors from units involved in the earlier Tenaru and Edson's Ridge battles plus malnourished naval troops from the original Guadalcanal garrison. The Japanese feared that they would be unable to prevent the Americans from taking the village of Kokumbona, which would cut off the retreat of the 2nd Infantry Division and seriously threaten the rear-area support and headquarters units of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal. In despair, Nakaguma discussed taking the regimental colors and seeking death in a final charge at the U.S. forces, but he was dissuaded by other officers on the 17th Army's staff.[32]

Early on 3 November, Marine units near Koli Point, east of the Lunga Perimeter, engaged 300 fresh Japanese troops that had just been landed by a Tokyo Express mission of five destroyers. This, plus the knowledge that a large body of Japanese troops was in the process of relocating to Koli Point after the defeat in the Henderson Field battle, led the Americans to believe that the Japanese were about to conduct a major attack on the Lunga Perimeter from the Koli Point area.[33] To discuss these developments, the Marine leaders on Guadalcanal met on the morning of 4 November. Twining recommended that the Matanikau offensive continue. Edson, Thomas, and Vandegrift, however, urged the abandonment of the offensive and a shift of forces to counter the Koli Point threat. Thus, that same day the 5th Marines and the Whaling Group were recalled to Lunga Point. The 2nd Marine's 1st and 2nd Battalions, plus the 1st Battalion, 164th Infantry took up positions about 2,000 yards (1,829 m) west of Point Cruz with plans to hold in that location. With their route of retreat still open, the Sendai (2nd) Division survivors began to reach Kokumbona this same day. Around this time, Nakaguma was killed by an artillery shell.[34]

Aftermath

After chasing away the Japanese forces at Koli Point, the U.S. renewed the western offensive towards Kokumbona on 10 November with three battalions under the overall command of U.S. Marine Colonel John M. Arthur. In the meantime, fresh Japanese troops from the 228th Infantry Regiment of the 38th Infantry Division landed by Tokyo Express over several nights beginning on 5 November and effectively resisted the American attack. After making small advances, at 13:45 on 11 November Vandegrift suddenly ordered all the American forces to return to the east bank of the Matanikau.[35]

Vandegrift ordered the withdrawal because of the receipt of intelligence from coastwatchers, aerial reconnaissance, and radio intercepts that a major Japanese reinforcement effort was imminent. Indeed, the Japanese were in the process of attempting to deliver the 10,000 remaining troops from the 38th Division to Guadalcanal in order to reattempt to capture Henderson Field. The resulting efforts by the Americans to stop this reinforcement attempt resulted in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the decisive naval battle of the Guadalcanal campaign in which the Japanese reinforcement effort was turned back.[36]

The Americans recrossed the Matanikau and attacked westward again beginning on 18 November but made slow progress against determined resistance from Japanese forces. The U.S. attack was halted on 23 November at a line just west of Point Cruz. The Americans and Japanese would remain facing each other in these positions for the next six weeks, until the ending stages of the campaign when U.S. forces began their final, successful push to drive Japanese forces from the island. Although the Americans had come close to overrunning the Japanese rear areas in the early November offensive, it would not be until the final stages of the campaign that the U.S. finally captured Kokumbona.[37]

Notes

- ↑ Number estimated by adding the numbers of six battalions (500 men each) to the 800 troops from the augmented Whaling Group battalion, and rounding up to account for support units involved. This is the number most likely actually engaged in the battle, not the total number of Allied troops on Guadalcanal, which at this time numbered over 20,000.

- ↑ Number estimated by counting the reported half strength of the 4th Infantry Regiment (about 800 troops) plus the 200 or so more rear-area support troops sent into the battle as it was going on.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 223.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 416, 724. The U.S. counted 239 bodies in the Point Cruz pocket and Frank adds that Japanese records record the total number of deaths for the entire operation as 410 although some of these may have occurred shortly before the operation commenced.

- ↑ Hogue, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 235–36.

- ↑ Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 14–15; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 18.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 96–99; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225; Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 137–38.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 202, 210–11.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 141–43, 156–58, 228–46, 681.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 156; Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 198–200.

- ↑ Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 204; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 270.

- ↑ Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 106.

- ↑ Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 96–101; Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 204–15; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 269–90; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 169–76; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 318–22. The 2nd Infantry was called Sendai because most of its soldiers were from Miyagi Prefecture.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 293–97; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 147–49; Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 140–42; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225.

- ↑ Shaw, First Offensive, p. 34; Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 63.

- ↑ Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 61; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 289–340; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 322–30; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 186–87; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, pp. 226–30; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 149–71. The Japanese troops delivered to Guadalcanal during this time comprised the entire 2nd (Sendai) Infantry Division, two battalions from the 38th Infantry Division, and various artillery, tank, engineer, and other support units. Kawaguchi's forces also included what remained of the 3rd Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment which was originally part of the 35th Infantry Brigade commanded by Kawaguchi during the Battle of Edson's Ridge.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 332–33; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 349–50; Rottman, Japanese Army, pp. 62–63; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 195–96; Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 157–58. The Marines lost 2 killed in the action. Japanese infantry losses are not recorded but were, according to Frank, "unquestionably severe." Griffith says that 600 Japanese soldiers were killed.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 336; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 353–62; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 197–204; Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 160–62; Miller, Cactus Air Force, pp. 147–51; Lundstrom, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 343–52.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 363–406, 418, 424, 553; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 122–23; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 204; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 337; Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 63.

- ↑ Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 121.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 343; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 135; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 214–15; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 411; Anderson, Guadalcanal, Shaw, First Offensive, pp. 40–41; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 130–31.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 411.

- ↑ Shaw, First Offensive, pp. 40–41; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 215; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 344; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 131; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 412; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 138.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 131–32; Hammel, Guadalcanal, pp. 138–39; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 412–13; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 215; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 345; Shaw, First Offensive, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 215; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 413.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 413.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 132; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 215–16; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 345; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 413–14.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 345; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 413–14; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 216; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 132–33.

- ↑ Jersey, Hell's Islands, pp. 299–300.

- ↑ Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 139; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 216; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 416; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 133; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 345; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 41.

- ↑ Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 136.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 216; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 416–18.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 413–20; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 41; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 139; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 345; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 216–17.

- ↑ Anderson, Guadalcanal; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 345; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 218; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 413–20; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 139; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 41. Frank states that Nakaguma was killed on 7 November.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 421, 424–25; Anderson, Guadalcanal; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 350–51; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 150.

- ↑ Anderson, Guadalcanal; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 350–51; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 425–27.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 357–58, 368; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 493–97, 570; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 50; Anderson, Guadalcanal; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 150–52; Jersey, Hell's Islands, pp. 309–310. The American forces involved in the 18 November attack included the US Army's 2nd Battalion, 182nd Infantry plus three battalions from the 8th Marine Regiment. The US Army's 1st and 3rd Battalions, 164th Infantry joined the attack on 20 November.

References

Books

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Frank, Richard (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-58875-4.

- Griffith, Samuel B. (1963). The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06891-2.

- Hammel, Eric (2007). Guadalcanal: The U.S. Marines in World War II. St. Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3148-4.

- Jersey, Stanley Coleman (2008). Hell's Islands: The Untold Story of Guadalcanal. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-616-2.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58305-7.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Dr. Duncan Anderson (consultant editor). Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Smith, Michael T. (2000). Bloody Ridge: The Battle That Saved Guadalcanal. New York: Pocket. ISBN 0-7434-6321-8.

Web

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). GUADALCANAL. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-8. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- Hough, Frank O.; Ludwig, Verle E.; Shaw, Henry I., Jr. "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Retrieved 16 May 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Shaw, Henry I. (1992). "First Offensive: The Marine Campaign For Guadalcanal". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Retrieved 25 July 2006.

- Zimmerman, John L. (1949). "The Guadalcanal Campaign". Marines in World War II Historical Monograph. Retrieved 4 July 2006.