_-2.jpg.webp)

Emeralds are green and sometime green with a blueish-tint precious gemstones that are mined in various geological settings. They are minerals in the beryl group of silicates. For more than 4,000 years, emeralds have been among the most valuable of all jewels. Colombia, located in northern South America, is the country that mines and produces the most emeralds for the global market, as well as the most desirable. It is estimated that Colombia accounts for 70–90% of the world's emerald market.[1] While commercial grade emeralds are quite plentiful, fine and extra fine quality emeralds are extremely rare. Colombian emeralds over 50 carat can cost much more than diamonds of the same size.

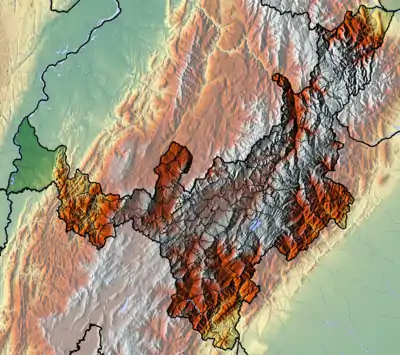

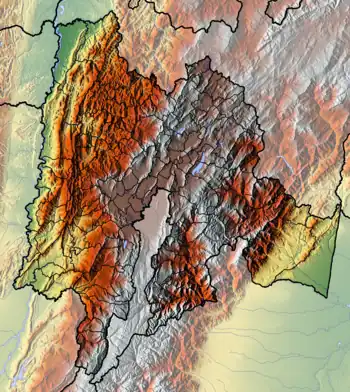

The Colombian departments of Boyacá and Cundinamarca, both in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, are the locations where most of the emerald mining takes place.[2]

Although the Colombian emerald trade has a rich history that dates as far back as the pre-Columbian era, the increase in worldwide demand for the industry of the gemstones in the early 20th century has led prices for emeralds to nearly double on the global market. Until 2016, the Colombian emerald trade was at the center of Colombia's civil conflict, which has plagued the country since the 1950s.[3]

History of emerald extraction

Pre-Colombian period

For thousands of years, emeralds have been mined and considered one of the world's most valuable jewels. The first ever recorded emeralds date back to ancient Egypt, where they were particularly admired by Queen Cleopatra. In addition to their aesthetic value, emeralds were highly valued in ancient times because they were believed to increase intelligence, protect marriages, ease childbirth, and thought to enable its possessor the power of predicting future events.[1]

Ancient emerald myths

An ancient Colombian legend exists of two immortal human beings, a man and a woman—named Fura and Tena—created by the Muisca god Are in order to populate the earth. The only stipulation by Are was that these two human beings had to remain faithful to each other in order to retain their eternal youth. Fura, the woman, however, did not remain faithful. As a consequence, their immortality was taken away from them. Both soon aged rapidly, and they eventually died. Are later took pity on the unfortunate beings and turned them into two crags protected from storms and serpents and in whose depths Fura's tears became emeralds. Today, the Fura and Tena peaks, rising approximately 840 and 500 meters, respectively, above the valley of the Minero River, are the official guardians of Colombia's emerald zone. They are located roughly 30 km north of the mines of Muzo, the location of the largest emerald mines in Colombia.[2]

Colonial and independence periods

Historians believe the indigenous people of Colombia mastered the art of mining as early as 500 AD. But Spanish Conquistadors are the ones who are credited with discovering and marketing globally what we now call Colombian emeralds. Colombia, during pre-colonial times, was occupied by Muzo indigenous people, who were overpowered by Spain in the mid 1500s.[4] It took Spain five decades to overpower the tribal Muzo people who occupied this entire mining area. Once in control, the Spanish forced this native, indigenous population to work the mining fields that it previously held for many centuries.

Monarchs and the gem-loving royalty in India, Turkey, and Persia eventually sought the New World treasures once the gems arrived in Europe. These new emerald owners expanded their private collections with spectacular artifacts bedazzled with emeralds between 1600 and 1820, the time frame of Spain's control over the Colombian mines. After Colombia's independence from Spain in 1819, the new government and other private mining companies assumed mining operations. Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these mines were periodically shut down numerous times because of political situations within the country.[5]

Regional geology

Western belt

M – Muzo

The western emerald belt of Colombia stretches across northwestern Cundinamarca and southwestern Boyacá to the extreme south of Santander, from La Palma and Topaipí in the southwest to La Belleza and Florián in the northeast.[6] The main municipalities of the western belt are:

The emeralds occur mainly in hydrothermal mineralizations in the Rosablanca, Paja, Muzo and Furatena Formations,[7][8] the latter named after the mythical cacica Furatena. Furatena was the owner of the finest emeralds of the Muzo territories before the Spanish conquest.[9]

Major mines of this area are:[10]

Small airports serving the western belt are Furatena Airport and Muzo Airport.

Eastern belt

C – Chivor

The eastern belt of the emerald region of the Eastern Ranges is located in the east of Cundinamarca and southeast of Boyacá, at around 110 kilometres (68 mi) distance from the western belt.[8] Main areas are:[11]

The emeralds occur mostly in the Macanal, Las Juntas and Guavio Formations.[8][11]

Major mines are:[10]

- Chivor mine

- Somondoco mine

- Gualí mine

- La Vega de San Juan

- Las Cruces

- El Diamante

- La Estrella

- El Perro

- La Mula

- El Toro

| Age | Paleomap | VMM | Guaduas-Vélez | W Emerald Belt | Villeta anticlinal | Chiquinquirá- Arcabuco | Tunja- Duitama | Altiplano Cundiboyacense | El Cocuy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maastrichtian |  | Umir | Córdoba | Seca | eroded | Guaduas | Colón-Mito Juan | ||||||

| Umir | Guadalupe | ||||||||||||

| Campanian | Córdoba | ||||||||||||

| Oliní | |||||||||||||

| Santonian | La Luna | Cimarrona - La Tabla | La Luna | ||||||||||

| Coniacian | Oliní | Villeta | Conejo | Chipaque | |||||||||

| Güagüaquí | Loma Gorda | undefined | La Frontera | ||||||||||

| Turonian |  | Hondita | La Frontera | Otanche | |||||||||

| Cenomanian | Simití | hiatus | La Corona | Simijaca | Capacho | ||||||||

| Pacho Fm. | Hiló - Pacho | Churuvita | Une | Aguardiente | |||||||||

| Albian |  | Hiló | Chiquinquirá | Tibasosa | Une | ||||||||

| Tablazo | Tablazo | Capotes - La Palma - Simití | Simití | Tibú-Mercedes | |||||||||

| Aptian | Capotes | Socotá - El Peñón | Paja | Fómeque | |||||||||

| Paja | Paja | El Peñón | Trincheras | Río Negro | |||||||||

| La Naveta | |||||||||||||

| Barremian |  | ||||||||||||

| Hauterivian | Muzo | Cáqueza | Las Juntas | ||||||||||

| Rosablanca | Ritoque | ||||||||||||

| Valanginian | Ritoque | Furatena | Útica - Murca | Rosablanca | hiatus | Macanal | |||||||

| Rosablanca | |||||||||||||

| Berriasian |  | Cumbre | Cumbre | Los Medios | Guavio | ||||||||

| Tambor | Arcabuco | Cumbre | |||||||||||

| Sources | |||||||||||||

Geology and characteristics of 'Colombian' emeralds

Colombian emeralds are found primarily in sedimentary Cretaceous black shales. Fault-driven fluidization and brecciation of host rock within the Colombian Cordillera during orogeny led to the transport of hydrothermal fluids and subsequent precipitation of beryl and other minerals within the black shales. These fluids have been described as “basinal brines”[12] and interacted chemically with organic material in the host shales, resulting in the precipitation of minerals such as calcite, dolomite, muscovite, pyrite, quartz, albite, and beryl.[12] Emeralds are a variety of the mineral beryl that owe their color to trace amounts of chromium and vanadium. The source of these trace elements in the case of Colombian Emeralds is believed to be from interaction of the parent hydrothermal fluid and the black shale host rock.

Colombian emeralds are much sought after, and not just because of their superb quality and color. A gem's value depends upon its size, purity, color and brilliance. Even when they are mined in the same area, each individual emerald has its own unique look that sets it apart from the rest. Dark green is considered to be the most beautiful, scarce, and valuable color for emeralds. An emerald of this color is considered rare and is only found in the deepest mines of Colombia.[4]

Mining areas in Colombia

_2.jpg.webp)

The eastern portion of the Andes, between the Boyacá and Cundinamarca departments, is where most Colombian emeralds are mined. The three major mines in Colombia are Muzo, Coscuez, and Chivor. Muzo and Coscuez are on long-term leases from the government to two Colombian companies, while Chivor is a privately owned mine. Muzo remains the most important emerald mine in the world to this date.[4]

The terms Muzo and Chivor do not always refer to the particular mines that carry the same name. Instead, the two terms, originating from the local indigenous language, often describe the quality and color of emeralds. Muzo refers to a warm, grassy-green emerald, with hints of yellow. Chivor, on the other hand, describes a deeper green color.[13]

There are also many other smaller emerald mines in Colombia which produce emeralds of all different grades, but these emeralds are usually of lower quality than the ones extracted from any of the three major mining areas.

Negative by-products of the Colombian emerald trade: The Green Wars

The Green Wars

Colombia has dealt with a civil war starting from the mid-1950s that is still taking place in the country today. This sixty-year conflict between left-wing guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitary groups, Colombian drug cartels, and the government, has displaced millions and has killed thousands of people. The emerald trade is at the center of funding this ongoing civil conflict in Colombia. Emeralds have helped fund many of the armed non-state actors (NSAs) involved in the Colombian internal conflict through means of emerald smuggling and the selling of these precious stones on the international black market.[14] The international demand for emeralds is currently at an all-time high, which secures the continued funneling of millions of dollars annually to illicit organizations in Colombia that acquire and sell emeralds on illegal premise in order to fund their existences.[15]

Dangers of the Colombian emerald trade

Because of their value on the international market, Colombian emeralds create a large illicit trade. Emerald smugglers, called guaqueros, poach on the mines, particularly along the Itoco River in the Muzo valley. During the day they scour the river beds and scavenge the mining fields for overlooked emeralds in private mines. By night, these smugglers try to rob safe houses that store the rough emeralds before they are able to be transported to safer areas. Guaqueros often compete with other guaqueros for the same loots, most of which return a large profit on the black market. This illegal mining activity is monitored by the National Police, but arrests are infrequent and jail sentences are usually short.[16]

Famous Colombian emeralds of history

- Duke of Devonshire Emerald – this emerald was named after the sixth Duke of Devonshire. This precious gem can now be viewed in a vault at the Natural History Museum in London.[4]

- Patricia Emerald – this 630-carat, di-hexagonal cut was first discovered in 1920. It is named after the mine owner's daughter, Patricia. This emerald currently resides in the American Museum of Natural History in New York.[4]

- Crown of the Andes – one of the most famous pieces of Colombian emerald-encrusted jewelry in the world. It has 453 stones totaling 1,521 carats. This piece includes the 45-carat Atahualpa Emerald, which was named after the last Inca emperor.[4]

- Gachalá Emerald – 858 carat emerald, found in Gachalá in 1967

- Hooker Emerald Brooch – brooch made from a Colombian emerald from an unknown mine, possibly Muzo

- Fura Emerald – the second-biggest emerald in the world, with 2.2 kilograms (4.9 lb) or 11,000 carat, found in Muzo, in 1999

- Tena Emerald – the most valuable emerald in the world, 400 grams (0.88 lb) or 2,000 carat, found in Muzo, in 1999

- La Lechuga – An 18th century Catholic monstrance composed of 1,485 emeralds from Muzo

See also

References

- 1 2 CiCeRi LLC Colombian Emeralds. "Emerald: The Queen of Gems". Archived from the original on 2013-08-25. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- 1 2 Proexport Colombia. "The Green Spell of Colombian Emeralds".

- ↑ "Colombia: Emeralds and Bullets". Time. July 12, 1971.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sanchez International. "The Fascinating History of Colombian Emeralds". Archived from the original on 2014-07-27. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- ↑ Genesis Gems. "Jewels of Colombia".

- ↑ Reyes et al., 2006, p.105

- ↑ Reyes et al., 2006, p.106

- 1 2 3 Rodríguez & Solano, 2000, p.86

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2013, p.98

- 1 2 "Emerald deposits of Colombia". Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- 1 2 Acosta & Ulloa, 2002, p.76

- 1 2 Branquet, Yannick; Cheilletz, Alain; Giuliani, Gaston; Laumonier, Bernard; Blanco, Oscar (1999). "Fluidized hydrothermal breccia in dilatant faults during thrusting: the Colombian emerald deposits". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 155 (1): 183–195. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.1999.155.01.14. ISSN 0305-8719.

- ↑ Lane, Kris (2010). Colour of Paradise: The Emerald in the Age of Gunpowder Empires. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300161311.

- ↑ "Fighting Colombia's Green War: Treasure of the emerald forest". The Independent. April 29, 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008.

- ↑ Bloomberg (March 15, 1998). "Colombia To Polish Up Lawless Emerald Trade". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ "Emeralds of Colombia". About.com: South America Travel. Archived from the original on 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

Bibliography

- Acosta, Jorge E., and Carlos E. Ulloa. 2002. Mapa geológico del Departamento de Cundinamarca 1:250,000 – Memoria Explicativa, 1–108. INGEOMINAS.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2013. Mitos y leyendas indígenas de Colombia – Indigenous myths and legends of Colombia. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Reyes, Germán; Diana Montoya; Roberto Terraza; Jaime Fuquen; Marcela Mayorga; Tatiana Gaona, and Fernando Etayo. 2006. Geología del cinturón esmeraldífero occidental Planchas 169, 170, 189, 190, 1–114. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2018-05-13.

- Rodríguez Parra, Antonio José, and Orlando Solano Silva. 2000. Mapa Geológico del Departamento de Boyacá – 1:250,000 – Memoria explicativa, 1–120. INGEOMINAS.

Further reading

- Branquet, Yannick; Bernard Laumonier; Alain Cheilletz, and Gaston Giuliani. 1999. Emeralds in the Eastern Cordillera of Colombia: Two tectonic settings for one mineralization. Geology 27. 597–600. Accessed 2017-01-05.

- Giuliani, Gaston; Alain Cheilletz; Carlos Arboleda; Victor Carrillo; Félix Rueda, and James H. Baker. 1995. An evaporitic origin of the parent brines of Colombian emeralds: fluid inclusion and sulphur isotope evidence. European Journal of Mineralogy 7. 151–165. Accessed 2017-01-05.

- Ortega Medina, Laura Milena. 2007. Tipología y condiciones de formación de las manifestaciones del sector esmeraldífero "Peña Coscuez" (municipio San Pablo de Borbur, Boyacá) (MSc.), 1–121. Universidad Industrial de Santander. Accessed 2017-01-05. Archived 2017-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Pignatelli, Isabella; Gaston Giuliani; Daniel Ohnenstetter; Giovanna Agrosì; Sandrine Mathieu; Christophe Morlot, and Yannick Branquet. 2015. Colombian Trapiche Emeralds: Recent Advances in Understanding Their Formation. Gems & Gemology LI. 222–259. .

- Puche Riart, Octavio. 1996. La explotación de las esmeraldas de Muzo (Nueva Granada), en sus primeros tiempos – The exploitation of the emeralds of Muzo (New Kingdom of Granada), the first period, 99–104. 3; Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Tequia Porras, Humberto. 2008. Asentamiento español y conflictos encomenderos en Muzo desde 1560 a 1617 - Spanish settlement and encomienda conflicts in Muzo from 1560 to 1617 (M.A.), 1–91. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Uribe, Sylvano E. 1960. Las esmeraldas de Colombia. Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia XVIII. 1–8. Accessed 2016-07-08.

External links

- (in Spanish) Las esmeraldas de Colombia