.svg.png.webp) Flag | |

An emerald from Muzo; The Muzo were known as the "Emerald People" | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 100,000 (including Colima)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Boyacá, Cundinamarca, | |

| Languages | |

| Cariban, Colombian Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional religion, Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Guane, Lache, Muisca, Panche |

The Muzo people were a Cariban-speaking[2][3][4] indigenous group who inhabited the western slopes of the eastern Colombian Andes. They were a highly war-like tribe who frequently clashed with their neighbouring indigenous groups, especially the Muisca.

The Muzo inhabited the right banks of the Magdalena River in the lower elevations of western Boyacá and Cundinamarca and were known as the Emerald People, thanks to their exploitation of the gemstone in Muzo. During the time of conquest, they resisted heavily against the Spanish invaders taking twenty years to submit the Muzo.

Knowledge about the Muzo people has been provided by chroniclers Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Pedro Simón, Juan de Castellanos, Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita and others.

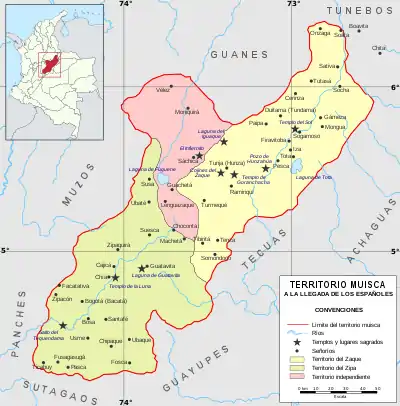

Muzo territory

The Muzo lived west of the Muisca.

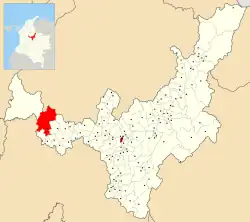

The Muzo were inhabiting the lower-elevation northwestern areas of the Cundinamarca department and western portion of the Boyacá Department, closer to the Magdalena River. Their northern neighbours were the Naura people,[5] the Panche in the south, and to the southeast the Muisca inhabited the higher-elevation Altiplano Cundiboyacense. Their western neighbours were the Colima people.[6]

The Muzo people were considered the first inhabitants of Boyacá, originally from Saboyá.[5][6] Their territory stretched from the thick forests surrounding the Carare River in the north at the border with Santander, the Río Negro in the south, in the east the Pacho River and the Ubaté-Chiquinquirá Valley, and the Magdalena River in the west.[5] Other sources limit the Muzo area with the Sogamoso, Suárez, Magdalena and Ermitaño rivers.[7]

Municipalities belonging to Muzo territories

| Name | Department | Elevation (m) urban centre |

Map |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coper | Boyacá | 950 |  |

| Maripí | Boyacá | 1249 |  |

| Muzo | Boyacá | 815 |  |

| Otanche | Boyacá | 1050 |  |

| Quípama | Boyacá | 1200 |  |

| Puerto Boyacá | Boyacá | 145 |  |

| San Pablo de Borbur | Boyacá | 830 |  |

| Tununguá | Boyacá | 1246 |  |

| Caparrapí | Cundinamarca | 1271 |  |

| Paime | Cundinamarca | 960 |  |

| Puerto Salgar | Cundinamarca | 177 |  |

| San Cayetano | Cundinamarca | 2700 |  |

| Topaipí | Cundinamarca | 1323 |  |

Description

.jpg.webp)

The Muzo were a people of healthy warriors with relatively short lifespans. Their health is attributed to the fact they were vegetarian, although other sources state they performed cannibalism.[1][6][8] The living spaces were always constructed in the vicinity of waterfalls or springs. The hotter climate of the lower terrain made them sweat and they bathed often. Many Muzo children were born covered with bristle hair, which made the superstitious mothers kill their babies.[5] The Muzo people lived naked and gave their children names of trees, animals and plants.[6]

The Muzo people performed agriculture, wood-working and production of ceramics. The elaboration of cloths using cotton or pita was done by the prostitutes of the Muzo.[5] They were most known for their exploitation of emeralds; until modern times Muzo was the world capital of the green gemstone. The Muzo society was divided into warriors, higher castes and chingamanas or chingamas; and slaves, commonly captured from other indigenous tribes. The oldest and bravest members of the community were considered the most important but were not caciques of their tribe.[6][9] A system of laws has not been noted.[5][6] Warfare and hunting were executed using poisoned arrows, as was a common practice with indigenous tribes in South America. The curare was obtained from poisonous plants and frogs.[4]

Religion

The religion of the Muzo consisted of few gods. Their creator god was called Are (he had a Muiscan counterpart called Chiminigagua). Maquipa was the deity who cured illnesses, and the Muzo adored the Sun and the Moon.[5] The Muzo people did not construct temples.[6]

Furatena

The two mountain peaks Fura and Tena, bordering the Carare River, were considered sacred by the Muzo people and believed they were the parents of humanity, creation of Are.[10] Fura and Tena taught the Muzo agricultural techniques, craftwork, and tactics of war. The myth of Furatena tells about a man with blue eyes and blonde beard, Zarbi, who entered the Muzo territories looking for the Fountain of Youth. On this journey, he met the beautiful Fura and they got together. The husband of Fura, Tena, was outraged, killed Zarbi and hung his body on the Fura mountain. After this cruel act he killed Fura and committed suicide, giving birth to the two pointing hills. According to the Muzo legends, the tears of Fura turned into emeralds and butterflies.[11]

The Muisca performed secret pilgrimages to Fura and Tena, avoiding the Muzo warriors attempting to discover them. In his work Compendio historial de la conquista del Nuevo Reino de Granada, Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita tells about the existence of a cacica named "Furatena", who was the owner of the finest emeralds of the Muzo territories. In the early years of the Spanish conquest, zipa Sagipa wanted to see Furatena.[12]

The emerald people

The first time the presence of emeralds in present-day Colombia was known to the Spanish was in 1514 in Santa Marta. During the campaign of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, the earliest contact with emeralds from the Eastern Ranges was made in 1537 in Chivor by Pedro Fernández de Valenzuela and Antonio Díaz de Cardoso. During the years of the Spanish conquest of the Muisca, the explorers heard about the emeralds from Muzo.[13] In 1544 Diego Martínez discovered the mines of Muzo.[14]

Although the accounts on the exploitation of silver, copper, iron and gold in the region vary, the chroniclers agree on the emeralds. To extract the emeralds from the surrounding rock, the Muzo used pointed wooden poles, called coa. The veins containing the minerals were cleaned with water. After extraction, the Muzo people elaborated the minerals.[5]

In the years before the arrival of the Spanish, the Muzo were in conflict with the Muisca. They hid their emeralds from their eastern neighbours and zipa Tisquesusa entered the Muzo terrain, killed a leader and cut his daughters to pieces to get information as to where the emerald deposits were located.[15]

In the 1980s, the treatment of the Muzo people to mine emeralds was deemed "dangerous" and people would be "killed."[16] The treatment of workers in the emerald mining industry has improved since then.[16]

History

It is estimated that the Muzo people pushed the Muisca who originally inhabited the lower-elevation terrain eastwards into the mountains of the Eastern Ranges by 1000 AD. The religious centres of the Muisca were occupied by the Muzo.[3]

Conquest

The Spanish colonisers had problems subjugating the Muzo in the 16th century. The Muzo resisted the Spanish forces, and the terrain full of creeks and ravines was inhospitable to the Spanish horses; the Muzo hid in the many natural forts the geography provided them.[17][18] When conquistador Pedro de Ursúa founded the city of Tudela close to the Muzo territories in 1552, the Muzo people attacked and razed the newly founded settlement, driving the Spanish back.[18]

The conquistador who subjugated the Muzo to the rule of the New Kingdom of Granada was Luis Lanchero, captain in the army of conquistador Nikolaus Federmann.[13] His first expedition with 40 men in 1539 failed, but he succeeded in subjugating the Muzo twenty years later in 1559 or 1560,[19] when he founded Santísima Trinidad de los Muzos, present-day Muzo on the remains of earlier Tudela.[19][20] During his second campaign, Lanchero almost lost his life after being hit by a poisoned arrow of the Muzo.[21]

1539–1559 – Luis Lanchero

| Settlement | Department | Date | Year | Notes | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muzo | Boyacá | 1539 | [22] |  | |

| Coper | Boyacá | 1540 | [23] |  | |

| Pauna | Boyacá | 1540–41 | [24] |  | |

| Quípama | Boyacá | 1541 | [25] |  | |

| Maripí | Boyacá | 1559 | [26] |  | |

See also

References

- 1 2 (in Spanish) Grupos étnicos primitivos en Boyacá

- ↑ (in Spanish) Culturas prehispánicas de Colombia

- 1 2 Tequia Porras, 2008, p.25

- 1 2 (in Spanish) Indios de Colombia

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (in Spanish) Colombia Cultural – SINIC

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Henao & Arrubla, 1820, p.126

- ↑ (in Spanish) Muzo and related indigenous groups territories

- ↑ Tequia Porras, 2008, p.28

- ↑ Tequia Porras, 2008, p.26

- ↑ (in Spanish) El génesis entre los muzos

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2013, p.95

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2013, p.98

- 1 2 Puche Riart, 1996, p.99

- ↑ Uribe, 1960, p.2

- ↑ (in Spanish) La reinsercíon de los esmeralderos – Semana

- 1 2 Otis, John (March 11, 2023). "Inside the emerald mines that make Colombia a global giant of the green gem". National Public Radio (NPR).

- ↑ Tequia Porras, 2008, p.35

- 1 2 (in Spanish) Tribus Indigenas En Colombia

- 1 2 Puche Riart, 1996, p.100

- ↑ (in Spanish) Muzo, capital de la esmeralda y emporio agrícola y ganadero – El Tiempo

- ↑ Tequia Porras, 2008, p.37

- ↑ (in Spanish) Official website Muzo

- ↑ (in Spanish) Official website Coper

- ↑ (in Spanish) Official website Pauna

- ↑ (in Spanish) Official website Quipama

- ↑ (in Spanish) Official website Maripí

Bibliography

- Henao, Jesús María, and Gerardo Arrubla. 1820. Historia de Colombia para la enseñanza secundaria – History of Colombia for the secondary education, 1–592. Indiana University. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2013. Mitos y leyendas indígenas de Colombia – Indigenous myths and legends of Colombia. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Puche Riart, Octavio. 1996. La explotación de las esmeraldas de Muzo (Nueva Granada), en sus primeros tiempos - The exploitation of the emeralds of Muzo (New Kingdom of Granada), the first period, 99–104. 3; Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Tequia Porras, Humberto. 2008. Asentamiento español y conflictos encomenderos en Muzo desde 1560 a 1617 - Spanish settlement and encomienda conflicts in Muzo from 1560 to 1617 (M.A.), 1–91. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Uribe, Sylvano E.. 1960. Las esmeraldas de Colombia. Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Colombia XVIII. 1–8. Accessed 2016-07-08.