In geometry, pinwheel tilings are non-periodic tilings defined by Charles Radin and based on a construction due to John Conway. They are the first known non-periodic tilings to each have the property that their tiles appear in infinitely many orientations.

Conway's tessellation

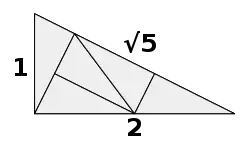

Let be the right triangle with side length , and . Conway noticed that can be divided in five isometric copies of its image by the dilation of factor .

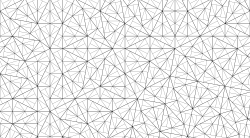

By suitably rescaling and translating/rotating, this operation can be iterated to obtain an infinite increasing sequence of growing triangles all made of isometric copies of . The union of all these triangles yields a tiling of the whole plane by isometric copies of .

In this tiling, isometric copies of appear in infinitely many orientations (this is due to the angles and of each being algebraically independent to over the reals.). Despite this, all the vertices have rational coordinates.

The pinwheel tilings

Radin relied on the above construction of Conway to define pinwheel tilings. Formally, the pinwheel tilings are the tilings whose tiles are isometric copies of , in which a tile may intersect another tile only either on a whole side or on half the length side, and such that the following property holds. Given any pinwheel tiling , there is a pinwheel tiling which, once each tile is divided in five following the Conway construction and the result is dilated by a factor , is equal to . In other words, the tiles of any pinwheel tilings can be grouped in sets of five into homothetic tiles, so that these homothetic tiles form (up to rescaling) a new pinwheel tiling.

The tiling constructed by Conway is a pinwheel tiling, but there are uncountably many other different pinwheel tilings. They are all locally undistinguishable (i.e., they have the same finite patches). They all share with the Conway tiling the property that tiles appear in infinitely many orientations (and vertices have rational coordinates).

The main result proven by Radin is that there is a finite (though very large) set of so-called prototiles, with each being obtained by coloring the sides of , so that the pinwheel tilings are exactly the tilings of the plane by isometric copies of these prototiles, with the condition that whenever two copies intersect in a point, they have the same color in this point.[1] In terms of symbolic dynamics, this means that the pinwheel tilings form a sofic subshift.

Generalizations

Radin and Conway proposed a three-dimensional analogue which was dubbed the quaquaversal tiling.[2] There are other variants and generalizations of the original idea.[3]

One gets a fractal by iteratively dividing in five isometric copies, following the Conway construction, and discarding the middle triangle (ad infinitum). This "pinwheel fractal" has Hausdorff dimension .

Use in architecture

Federation Square, a building complex in Melbourne, Australia, features the pinwheel tiling. In the project, the tiling pattern is used to create the structural sub-framing for the facades, allowing for the facades to be fabricated off-site, in a factory and later erected to form the facades. The pinwheel tiling system was based on the single triangular element, composed of zinc, perforated zinc, sandstone or glass (known as a tile), which was joined to 4 other similar tiles on an aluminum frame, to form a "panel". Five panels were affixed to a galvanized steel frame, forming a "mega-panel", which were then hoisted onto support frames for the facade. The rotational positioning of the tiles gives the facades a more random, uncertain compositional quality, even though the process of its construction is based on pre-fabrication and repetition. The same pinwheel tiling system is used in the development of the structural frame and glazing for the "Atrium" at Federation Square, although in this instance, the pin-wheel grid has been made "3-dimensional" to form a portal frame structure.

References

- ↑ Radin, C. (May 1994). "The Pinwheel Tilings of the Plane". Annals of Mathematics. 139 (3): 661–702. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.44.9723. doi:10.2307/2118575. JSTOR 2118575.

- ↑ Radin, C., Conway, J., Quaquaversal tiling and rotations, preprint, Princeton University Press, 1995

- ↑ Sadun, L. (January 1998). "Some Generalizations of the Pinwheel Tiling". Discrete and Computational Geometry. 20 (1): 79–110. arXiv:math/9712263. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.241.1917. doi:10.1007/pl00009379. S2CID 6890001.

External links

- Pinwheel at the Tilings Encyclopedia

- Dynamic Pinwheel made in GeoGebra