The following WikiProject London Transport articles have been selected as representing the scope of the project and are displayed in random rotation on the London transport Portal.

Usage

The template used for the creation of these sub-pages is located at {{Selected article}}

- Add a new Selected article to the next available subpage.

- Update "end=" to new total for its {{Random subpage}} on the main page.

Selected articles 1

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/1

The name has been used since 2007, when TfL took over the majority of the 'Metro' sector from the Silverlink train operating company franchise. In 2010 it is planned that the Overground network will include the East London Line (formerly part of London Underground) which is being extended to connect with the North London Line. This section is currently closed.

The Overground is part of the National Rail network, run as a rail franchise by the train operating company London Overground Rail Operations Limited (LOROL), but the contracting authority is TfL rather than central Government. This arrangement is similar to the model adopted for Merseyrail. The lines continue to be owned and maintained by Network Rail except for the Dalston-New Cross section of the East London Railway, which will remain TfL property when it becomes part of the Overground.

The Overground is a commuter rail system, as many of the lines share traffic with freight services, although there is an intention to introduce metro-style frequencies eventually on all routes.

Selected articles 2

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/2

Both the 1996 Stock and the similar 1995 Stock found on the Northern line were built by Alstom in Birmingham, The 1995 and 1996 stock have different seating layouts and cab designs. The trains are capable of automatic train operation as on the Victoria line, although this will not be enabled until a signalling upgrade in some years' time.

Selected articles 3

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/3

All the trains are computer-controlled and have no driver: a passenger service agent (PSA) on each train is responsible for patrolling the train, checking tickets, making announcements, and controlling the doors. PSAs can also take control of the train in case of computer failure or emergency. Operation and maintenance of the DLR has been carried out by a private franchise since 1997. The current franchise, due to expire in April 2013, belongs to Serco Docklands Ltd, a company jointly formed by Serco and the former DLR management team.

Since opening on 31 August 1987, the system has been extended and upgraded many times to increase the extent of its coverage and increase capacity with new branches being constructed to take the network to Bank in the City of London, London City Airport, Lewisham and Woolwich Arsenal.

Selected articles 4

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/4

The new line was to have been called the Fleet Line after the River Fleet, but the project was renamed for Queen Elizabeth II's 1977 Silver Jubilee and because the original plans to go east towards Fleet Street had been postponed. The eastward extension was eventually cancelled and a revised route south running south of the River Thames via Waterloo and London Bridge was planned to take the line to the London Docklands, Canary Wharf and Stratford. The Jubilee Line Extension branched from the original line south of Green Park Underground station and opened in sections during 1999. The Jubilee line platforms at Charing Cross were closed when the final section opened.

Selected articles 5

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/5

The first coordinated map of London's underground railway lines was produced in 1908 and highlighted the routes on a traditional map also showing other geographical features. During the 1920s attempts were made to make the map more readable by removing unnecessary information until only the River Thames remained; the maps remained geographic.

The current version is a schematic diagram and no longer represents geography but relationships. It considerably distorts the actual relative positions of stations, but accurately represents their sequential and connective relationships with each other and their placement within the zones. The basic design concepts, especially that of mapping topologically, have been widely adopted around the world for other route maps.

The original schematic map was designed in 1931 by Underground employee Harry Beck, who realised that, because the railway ran mostly underground, the physical locations of the stations were irrelevant to the travellers; only the topology of the system mattered. Beck based his diagram on a similar mapping system for underground sewage systems.

Selected articles 6

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/6

Stratford station was opened in 1839 by the Eastern Counties Railway (ECR). London Underground Central line services started on 4 December 1946. Services were extended to Leyton on 5 May 1947 and then on to the former London and North Eastern Railway branch lines to Epping, Ongar and Hainault progressively until 1949.

The Docklands Light Railway opened on 31 August 1987 reusing redundant rail routes through the Bow and Poplar areas to reach the new Docklands developments on the Isle of Dogs.

The Low Level station (served by the North London line) underwent a major rebuilding programme in the late 1990s as part of the Jubilee Line Extension works. This saw the construction of a large steel and glass building designed by Wilkinson Eyre and a new replacement booking hall. The Jubilee line opened to passengers on 14 May 1999, with services initially running only as far as Canning Town station.

Selected articles 7

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/7

The Oyster card may have been inspired by Hong Kong's transport system, which uses the similar Octopus card. As with the Octopus card and other pay-as-you-go smartcards, also notably in Japan, there is the potential for future expansion of the Oyster card to act as an e-money payment system.

Travellers touch the card to a distinctive yellow circular reader (a Cubic Tri-Reader) positioned on automated barriers at London Underground stations to 'touch in' and 'touch out' at the start and end of a journey (contact is not necessary, but the range of the reader is only a centimetre or so). Tram stops and buses also have readers, on the driver's ticket machine or, in the case of articulated buses, near the other entrance doors as well. Oyster cards can be used to store both period travelcards and bus passes (of one week or more), and a pay-as-you-go balance.

The system is asynchronous with the most up-to-date balance and ticket data held electronically on the card rather than in the central database. The main database is updated periodically with information received from the card by barriers and validators. Tickets purchased online or over the telephone are "loaded" at a preselected barrier or validator.

Selected articles 8

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/8

The line has a complicated history and the current complex arrangement of two northern branches, two central branches and the southern branch reflects its genesis as three separate railway companies that were brought together and combined in the 1920s and 1930s. The original routes were extended several times so that by 1926 the line served Edgware in the north and Morden in the south. Ambitious plans to take over and incorporate London & North Eastern Railway's Northern Heights branch lines and extend the line to Bushey were mostly cancelled following the Second World War. (Full article...)

Selected articles 9

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/9

The scheme makes use of CCTV cameras to record vehicles entering and exiting the zone. Cameras can record number plates with a 90% accuracy rate through automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) technology. There are also a number of mobile camera units which may be deployed anywhere in the zone. The majority of vehicles within the zone are captured on camera. The cameras take two still pictures in colour and black and white and use infrared technology to identify the number plates. These identified numbers are checked against the list of payees overnight by computer; unrecognised plates are checked manually.

Selected articles 10

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/10

%252C_1979_Leyland_Titan_(B15)%252C_Gants_Hill%252C_route_66%252C_19_April_1980.jpg.webp)

The Titan entered service in 1978 with London Transport, which ordered a total of 1,425 of the model up until 1984. Titan buses operated mainly in the east and south-east of the capital. The model was withdrawn in stages from 1992 with the final bus being taken out of service in 2003. (Full article...)

Selected articles 11

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/11

The station was opened as Westminster Bridge in 1868 by the District Railway when the company opened the first section of its line from South Kensington.

As part of the Jubilee Line Extension the station was completely reconstructed to designs by Michael Hopkins & Partners. During the reconstruction, a 39 metres (128 ft) deep void was excavated underneath the old station to house the escalators, lifts and stairs to the deep-level Jubilee line platforms. This made it the deepest ever excavation in central London. One of the most difficult problems the engineers faced was to construct the station around the Circle and District line tracks, which continued in service throughout the construction. The tracks had to be lowered by 300 millimetres (0.98 ft), an operation achieved a few millimetres at a time during the few hours each night that the system was closed. Nothing of the old station remains. (Full article...)

Selected articles 12

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/12

The line traces its origins to the Central London Railway (CLR) incorporated in 1891 for a route between Shepherd's Bush and Bank. The railway opened to passengers on 30 July 1900 with trains initially hauled by electric locomotives, although complaints about the vibrations caused by the engines led to electric multiple unit operation being introduced within a few years. The distinctive station buildings, few of which survive, were designed by the architect Harry Bell Measures. The CLR was extended to Liverpool Street in 1912 and Ealing Broadway in 1920. The current name came into use in 1937 and the line was extended east and west from the central area taking over passenger services on former London & North Eastern Railway and Great Western Railway routes in the late 1940s. (Full article...)

Selected articles 13

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/13

The station was originally opened by the Central London Railway in 1900 and an interchange was provided with the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway when it opened in 1906. The original station buildings are each side of the junction of Oxford Street and Argyll Street. Access to the platforms was originally by separate sets of lifts, but the first sets of escalators were installed in 1914. More escalators were installed in 1923 and 1928, although the lifts continued to be used.

The current arrangement of the station dates from the reconstruction in the 1960s for the Victoria line. A new ticket hall was excavated beneath under the road junction using a temporary bridge structure called the umbrella spanning the works to keep the junction open. New escalators were provided for the Victoria line which was constructed to have a cross platform interchange with the Bakerloo line. The station is third busiest on the London Underground network with almost 73 million passengers entering and exiting the station in 2008. (Full article...)

Selected articles 14

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/14

Delays in finding the funding, opposition from the two mainline companies that the line was intended to connect, and World War I, led to the start of construction work being delayed until 1927. The line was completed and opened in January 1930, although the planned extension of the MDR was not implemented and the service was provided by the Southern Railway. The opening of the line stimulated residential development as planned, but competition from the London Underground's City and South London Railway, which had its terminus at Morden, meant that the line did not achieve the hoped for passenger numbers. (Full article...)

Selected articles 15

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/15

The current route of the London section of the A1 road was mainly designated as such in 1927. It comprises a number of historic streets in central London and the former suburbs of Islington, Holloway and Highgate and long stretches of purpose-built new roads in the outer London borough of London Borough of Barnet, built to divert traffic away from the congested suburbs of Finchley and High Barnet.

The London section of the A1 is one of London's most important roads. It links North London to the M1 motorway and the A1(M) motorway, and consequently serves as Central London's primary road transport artery to the Midlands, Northern England and Scotland. It also connects a number of major areas within London, and sections of it serve as the High Street for many of the now-joined villages that make up north London. (Full article...)

Selected articles 16

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/16

St Pancras is termed as the "Cathedral of the railways" and includes two of the most celebrated structures built in Britain in the Victorian era. The main trainshed (completed 1868), by the engineer William Henry Barlow, was the largest single-span structure built up to that time. In front of it is St Pancras Chambers, formerly the Midland Grand Hotel (1868-77), one of the most impressive examples of Victorian gothic architecture. Designed by architect George Gilbert Scott, the building initially appears to be in a polychromatic Italian Gothic style - inspired by John Ruskin's Stones of Venice - but on a closer viewing, it incorporates features from a variety of periods and countries. From such an eclectic approach Scott anticipated that a new genre would emerge. Access to the spectacular interiors of the former hotel is by tour only. (Full article...)

Selected articles 17

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/17

The museum also operates the London Transport Museum Depot at Acton in west London, which provides 6,000 square metres of storage space for over 370,000 items of all types including very large items such as rolling stock, buses and trams. The depot is no permanently open to the public, but hosts a number of open days throughout the year. (Full article...)

Selected articles 18

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/18

When opened in 1890, it served six stations and ran for a distance of 5.1 kilometres (3.2 mi) in a pair of tunnels between the City of London and Stockwell, passing under the River Thames. The small size of the carriages with their high-backed seating led to them being nicknamed padded cells. The railway was extended several times north and south; eventually serving 22 stations over a distance of 21.7 km (13.5 mi) from Camden Town in north London to Morden in Surrey.

Although the C&SLR was well used, the company struggled financially. In 1913, the C&SLR became part of the Underground Group of railways and, in the 1920s, it underwent major reconstruction works before its merger with the Group's Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway, to form what is now the Northern line. In 1933, the C&SLR and the rest of the Underground Group was taken into public ownership. (Full article...)

Selected articles 19

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/19

In 1863, the tunnel was purchased by the East London Railway company for conversion to a railway tunnel. The first trains ran through the tunnel in 1869. From 1884 Metropolitan Railway and District Railway services used the tunnel and it later became part of the London Underground's Metropolitan line and finally it's East London line. In 2007 the tunnel was closed whilst the East London line was converted to become part of the London Overground network. It was reopened in 2010. Recognising its architectural and engineering importance, the tunnel is a Grade II* listed building. (Full article...)

Selected articles 20

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/20

The bridge was constructed between 1886 and 1894 with the Gothic style of the finished bridge designed by George D. Stevenson after Jones' death. The bridge is 800 feet (240 m) long with towers 213 feet (65 m) tall. The combined width of the bascules is 200 feet (61 m) and the suspension bridges both sides are each 270 feet (82 m) long. (Full article...)

Selected articles 21

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/21

The line was built as part of Edward Watkin's scheme to turn his Metropolitan Railway (MR) into a direct rail route between London and Manchester, and it was envisaged that a station outside Chesham would be an intermediate stop on a through route running north to connect with the London and North Western Railway (LNWR). Although the relationship with the LNWR soured, it was decided to build the route as far as Chesham anyway. The line opened in 1889 and Chesham became the terminus of the MR. In 1892 the MR opened an extension to Aylesbury and on to Verney Junction and the Chesham line became a branch line. In 1933 the Metropolitan Railway became part of the London Underground. For most of its time as a branch the service operated as a shuttle, but, since the introduction of new rolling stock in 2010 the branch operates a through service to and from London. (Full article...)

Selected articles 22

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/22

Intended for posters and signage, Johnston's design originally consisted of just capital letters, numbers and punctuation symbols but the widening of its usage saw the addition of lower case characters and different type weights. The typeface is sans-serif and features a perfectly circular capital letter O and diamond-shaped full-stop and dots over the letters i and j. The current version of Johnston in use was designed to be slightly heavier than the original and is named New Johnston. (Full article...)

Selected articles 23

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/23

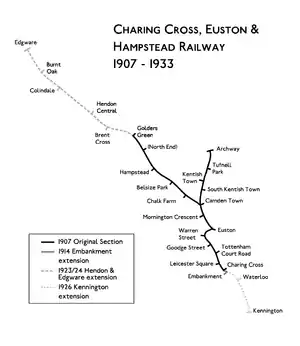

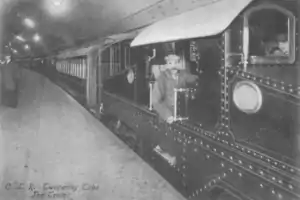

When opened in 1907, the line served 16 stations and ran for a distance of 12.34 kilometres (7.67 mi) in a pair of tunnels between its southern terminus at Charing Cross and its two northern termini at Archway and Golders Green. Later extensions took the railway to Edgware and under the River Thames to Kennington, serving a total distance of 22.84 kilometres (14.19 mi) and 23 stations.

In the 1920s, connections were made to another of London's deep-level tube railways and services on the two lines were merged to become what was later named the Northern line. In 1933, the CCE&HR and the rest of the Underground Group was taken into public ownership. Today, the CCE&HR's tunnels and stations form the Charing Cross and Edgware branches and part of the High Barnet branch of the London Underground's Northern line. (Full article...)

Selected articles 24

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/24

The bridge was painstakingly disassembled with each stone block receiving a reference number to enable correct reassembly. Re-erection started in 1968 and was completed in 1971 with the stones being erected as a facing around a reinforced concrete structure. (Full article...)

Selected articles 25

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/25

The London terminus is St Pancras International, with the other British calling points being at Ebbsfleet International and Ashford International in Kent. Calling points in France are Calais-Fréthun and Lille-Europe, with the main Paris terminus at Gare du Nord. Trains to Belgium terminate at Midi/Zuid station in Brussels. In addition, there are limited services from London to Disneyland Paris at Marne-la-Vallée – Chessy, and to seasonal destinations in southern France.

The service is operated by eighteen-coach Class 373/1 trains which run at up to 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph) on a network of high-speed lines. The LGV Nord line in France opened before Eurostar services began in 1994, and newer lines enabling faster journeys were added later—HSL 1 in Belgium and High Speed 1 in southern England. The French and Belgian parts of the network are shared with Paris–Brussels Thalys services and also with TGV trains. In the United Kingdom the two-stage Channel Tunnel Rail Link project was completed on 14 November 2007 and renamed High Speed 1, when the London terminus of Eurostar transferred from Waterloo International to St Pancras International. (Full article...)

Selected articles 26

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/26

The railway company was established in 1889, funding for construction was obtained in 1895 through a syndicate of financiers and work took place from 1896 to 1900. When opened, the CLR served 13 stations and ran completely underground in a pair of tunnels for 9.14 kilometres (5.68 mi) between its western terminus at Shepherd's Bush and its eastern terminus at the Bank of England, with a depot and power station to the north of the western terminus. After a rejected proposal to turn the line into a loop, it was extended at the western end to Wood Lane in 1908 and at the eastern end to Liverpool Street station in 1912. In 1920, it was extended along a Great Western Railway line to Ealing to serve a total distance of 17.57 kilometres (10.92 mi).

After initially making good returns for investors, the CLR suffered a decline in passenger numbers due to increased competition from other underground railway lines and new motorised buses. In 1913, it was taken over by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), operator of the majority of London's underground railways. In 1933 the CLR was taken into public ownership along with the UERL. (Full article...)

Selected articles 27

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/27

In 1908, local resident Walter Hammerton began hiring out boats to leisure users from a boathouse opposite Marble Hill House, and in 1909 began to operate a regular ferry service across the river at this point using a 12-passenger clinker-built skiff, charging 1d per journey. In 1913, William Champion, and Lord Dysart, operators of the nearby Twickenham Ferry, took legal action against Hammerton to remove his right to operate the ferry. Although Hammerton won the initial case, the judgement was reversed on appeal. Following considerable public interest in the case, a public subscription raised the funds for Hammerton to take the case to the House of Lords, which ruled in his favour on 23 July 1915. (Full article...)

Selected articles 28

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/28

Beginning as Walworth Road, the A215 becomes Camberwell Road—much of which is a conservation area—after entering the former Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell. Crossing the A202, the A215 becomes Denmark Hill, originally known as Dulwich Hill, but renamed in 1683 to commemorate the marriage of Princess Anne (later Queen Anne) to Prince George of Denmark. After passing Herne Hill railway station the road becomes Norwood Road, Knights Hill, and then Beulah Hill at its crossroads with the A214. Beulah Hill was the site of Britain's first independent television transmitter, built by the Independent Television Authority in 1955. Descending towards South Norwood the A215 becomes South Norwood Hill and then Portland Road, just after crossing the A213. A short section starting at the junction with Woodside Green is known as Spring Lane, leading to Shirley Road, the final section into Shirley, Croydon. (Full article...)

Selected articles 29

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/29

The first bridge was a toll bridge commissioned by John, Earl Spencer, who had acquired the rights to operate the ferry. Although a stone bridge was planned, difficulties in raising investment meant that a cheaper wooden bridge was built instead. Designed by Henry Holland, it was opened to pedestrians in November 1771 and to vehicles in 1772. The bridge was poorly designed and dangerous and, due to its location on a bend in the river, boats often collided with it. To reduce the dangers to shipping, two piers were removed and the sections of the bridge above them were strengthened. Despite its problems, the bridge was the last surviving wooden bridge on the Thames in London and was the subject of paintings by many significant artists such as J. M. W. Turner, John Sell Cotman and James McNeill Whistler.

In 1879 the bridge was taken into public ownership, and in 1885 it was replaced with the existing bridge, designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette and built by John Mowlem & Co. The narrowest surviving road bridge over the Thames in London, it is one of London's least busy Thames bridges. (Full article...)

Selected articles 30

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/30

The Tower Subway was eventually superseded by Tower Bridge which was built a few hundred yards downriver in 1894. In 1898, the Subway was closed and was then used by the London Hydraulic Power Company for hydraulic tubes and water mains. It survived a World War II bomb blast which resulted in at point of impact the radius reduced to 1.2m and was found to still be in excellent condition. Nowadays the tunnel is used for mains and telecommunication cables. (Full article...)

Selected articles 31

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/31

The railway was built by the Grand Union Canal Company as part of the leisure facilities at the Ruislip Lido which is a reservoir for the canal. When the Grand Union was nationalised in 1948 to be part of the British Transport Commission, control of the Lido and its railway passed into the hands of Ruislip-Northwood Urban District Council which, in 1965, became part of the London Borough of Hillingdon. Under local authority control the railway was neglected and, following an accident in 1978, it was closed. In 1980, the volunteer run Ruislip Lido Railway Society Limited reopened the railway using a petrol powered engine and gradually expanded the route around the Lido and added additional rolling stock. With Pinewood Studios nearby, the Lido has been used as a filming location for scenes in a number of films including The Young Ones starring Cliff Richard. (Full article...)

Selected articles 32

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/32

The bridge was built between 1774 and 1777 to the designs of James Paine and Kenton Couse, as a replacement for a ferry crossing which connected Richmond town centre on the south bank with its neighbouring district of East Twickenham (St. Margarets) to the north. Its construction was privately funded by a tontine scheme, to pay for which tolls were charged until 1859.

The bridge was widened and slightly flattened in 1937–40, but otherwise still conforms to its original design. The eighth Thames bridge to be built in what is now Greater London, it is today the oldest surviving Thames bridge in London. (Full article...)

Selected articles 33

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/33

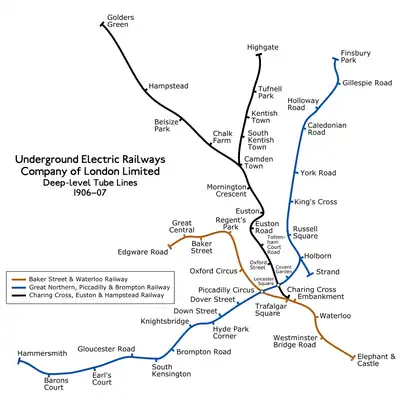

When it opened in 1906, the GNP&BR's line served 22 stations and ran for 14.17 kilometres (8.80 mi) between its western terminus at Hammersmith and its northern terminus at Finsbury Park. A short 720-metre (2,362 ft) branch connected Holborn to the Strand. Within the first year of opening it became apparent to the management and investors that the estimated passenger numbers for the GNP&BR and the other UERL lines were over-optimistic. Despite improved integration and cooperation with the other tube railways, the GNP&BR struggled financially. In 1933 it and the rest of the UERL were taken into public ownership. Today, the GNP&BR's tunnels and stations form the core central section of the London Underground's Piccadilly line. (Full article...)

Selected articles 34

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/34

_route_83_branding_Piccadilly_Circus.jpg.webp)

A pioneering design, the Routemaster outlasted several of its replacement types in London. The unique features of the standard Routemaster were both praised and criticised. The open platform, while exposed to the elements, allowed boarding and alighting away from stops; and the presence of a conductor allowed minimal boarding time and optimal security, although the presence of conductors produced greater labour costs. The traditional red Routemaster has become one of the famous features of London, with much tourist paraphernalia continuing to bear Routemaster imagery, and with examples still in existence around the world. (Full article...)

Selected articles 35

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/35

The rivers have been subject to change over centuries, with Alfred the Great diverting the river in 896 to create a second channel, and Queen Matilda bridging both channels around 1110. Because the river system was tidal as far as Hackney Wick, several of the mills were tide mills, including those at Abbey Mills and those at Three Mills, one of which survives. Construction of the New River in the seventeenth century to supply drinking water to London, with subsequent extraction by waterworks companies, led to a lowering of water levels, and the river was gradually canalised to maintain navigation. Significant changes occurred with the creation of the Lee Navigation in 1767, which resulted in the construction of the Hackney Cut and the Limehouse Cut, allowing barges to bypass most of the back rivers. A major reconstruction of the rivers took place in the 1930s, authorised by the River Lee (Flood Relief) Act, but by the 1960s, commercial usage of the waterways had largely ceased. Deteriorating infrastructure led to the rivers dwindling to little more than tidal creeks and they were categorised in 1968 as having no economic or long term future.

However, British Waterways decided that their full restoration was an important aim in 2002, and the construction of the main stadium for the 2012 Summer Olympics on an island formed by the rivers has provided funding to construct a new lock and sluices which have stabilised water levels throughout the Olympic site. It was hoped that significant amounts of materials for the construction of the Olympic facilities would be delivered by barge, but this did not happen. Improvements to the channels which form a central feature of the Olympic Park have included the largest aquatic planting scheme ever carried out in Britain. (Full article...)

Selected articles 36

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/36

The station was the first of three planned on an extension of the Northern line's Edgware branch from Edgware station to the south up to Bushey Heath. The other two stations planned to the north were Elstree South and Bushey Heath. For Brockley Hill, other names were considered such as "Edgwarebury", "Edgebury", "North Edgware", "Canons" and "All Souls".

The extension was planned in 1935 as part of the Northern Heights project to electrify steam-operated London and North Eastern Railway branch lines and incorporate them into the Northern line. Construction began in June 1939 but was halted by the start of the Second World War. When work stopped, the route had been laid out, some earthworks constructed and a viaduct at the site of Brockley Hill station had been started. After the war, the introduction of Green Belt legislation preventing the residential development that the station would have served led to the cancellation of the project. The viaduct arches were partially demolished leaving the brickwork stumps that remain in a field today. (Full article...)

Selected articles 37

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/37

The railway was a precursor of parts of the London Underground's Northern line through its 1930s inclusion in the core of an ambitious expansion plan for that line. The EH&LR was to be transferred to the London Underground and electrified. Connections were to be constructed to the Northern line at Highgate and Edgware and to the Northern City Line, with an extension from Edgware to Bushey Heath. Works were stopped by the outbreak of the Second World War and only the work on the sections from Highgate to High Barnet and from Finchley Central to Mill Hill East were completed. The remainder of the line was closed in by British Railways the 1950s and is now disused. (Full article...)

Selected articles 38

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/38

When the Channel Tunnel was opened, Eurostar trains ran on standard commuter tracks through Kent and south London to Waterloo International, running at speeds much below their maximum due to speed limits and competing rail traffic. High Speed 1 was constructed to provide a dedicated fast route between the tunnel and London and was constructed and opened in two sections.

The first section of the line was opened in September 2003 and ran from the tunnel to North Kent where trains transferred from the high speed tracks to the Kent and South London commuter network to run to Waterloo International. The second section of the line, travelling under the River Thames and into London St Pancras, opened on 14 November 2007. Built at a cost of £5.2bn, the link allows trains to travel at speeds of 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph), cutting pre-2003 Eurostar journey times by 40 minutes and increasing service frequency. It is now possible to travel from London St Pancras to Paris Gare du Nord in 2 hours 15 minutes, and to Brussels South in 1 hour 51 minutes. Domestic high speed commuter services from Kent to St Pancras started in December 2009 running at speeds of up to 225 kilometres per hour (140 mph). (Full article...)

Selected articles 39

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/39

Selected articles 40

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/40

The origin of the game is not clear. One account is that the game was invented to vex the series producer, who was unpopular with the panellists. Another is that it was invented at a Soho actors' club to infuriate boorish customers. In introducing the game, the chairman will generally elaborate on the obscure and unknown rules by advising the players that specific rule variations will be used for that round, such as "Trumpington's Variations," or "Tudor Court Rules". Listeners unaware of the satirical nature of the game who have asked for the rules are told that "N F Stovold’s Mornington Crescent: Rules and Origins" is out of print. (Full article...)

Selected articles 41

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/41

Following the 1933 transfer of the Metropolitan Railway to public ownership to become the Metropolitan line of London Transport, Westcott station became a part of the London Underground, despite being over 40 miles (60 km) from central London. The management of London Transport believed it very unlikely that the line could ever be made viable, and Westcott station was closed, along with the rest of the line, in November 1935. The station building and its associated house are the only significant buildings from the Brill Tramway to survive other than the former junction station at Quainton Road. (Full article...)

Selected articles 42

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/42

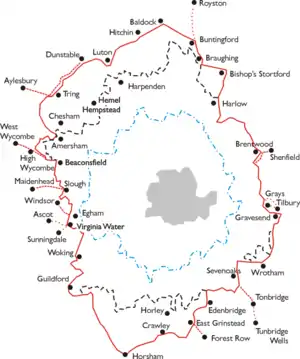

The plan was hugely ambitious and met, almost immediately, with opposition from a number of directions including residents associations, London Borough councils, the Treasury and the Department of Transport. Despite this opposition the GLC continued to develop its plans and began the construction of some of the earlier parts of the scheme. In 1972, in an attempt to placate the plan's vociferous opponents, the GLC dropped parts of the two innermost ringways, but the scheme was cancelled in 1973 at which point only three sections had been constructed – the East Cross Route, part of the West Cross Route and the Westway.

Significant sections of the report's proposals have also been built over the subsequent years including improvements to the North Circular Road and, most importantly, the M25 and M26 motorways which were formed from an amalgamation of parts of the two outermost rings. (Full article...)

Selected articles 43

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/43

The viaduct was designed by Sir John Fowler and Walter Brydone, chief engineer of the Great Northern Railway (GNR) and was opened with the company's single track Edgware, Highgate and London Railway on 22 August 1867.

In the 1920s, the London and North Eastern Railway (successor to the GNR) planned to electrify the line, but work was not carried out until the 1930s when it was done as part of the London Transport's Northern Heights plan in preparation for a transfer of the line to the Northern line. The start of the Second World War prevented the plans being completed and only the section of the line to Mill Hill East was electrified and reopened by London Transport in 1941. British Rail freight services to Edgware continued on the line until 1964 when it was closed west of Mill Hill East. (Full article...)

Selected articles 44

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/44

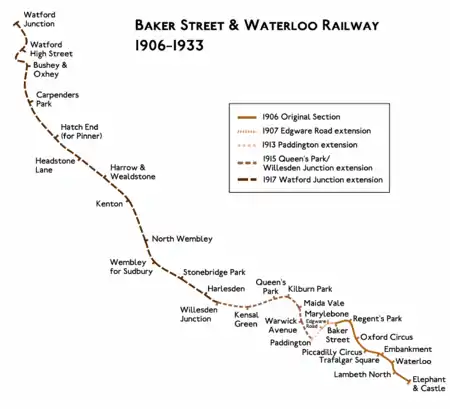

When opened in 1906, the BS&WR's line ran completely underground in a pair of tunnels for 5.81 kilometres (3.61 mi) between its Baker Street and Elephant and Castle. By 1913 extensions had taken the northern end of the line to Paddington. Between 1915 and 1917, it was further extended to Queen's Park and then to Watford; a total distance of 33.34 kilometres (20.72 mi).

Within the first year of opening it became apparent to the management and investors that the estimated passenger numbers for the BS&WR and the other UERL lines were over-optimistic. Despite improved integration and cooperation with the other tube railways and the later extensions, the BS&WR struggled financially. In 1933, the BS&WR was taken into public ownership along with the UERL and became part of London Transport. (Full article...)

Selected articles 45

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/45

Like the other stations Charles Holden designed for the extension, Arnos Grove was built in a modern European style using brick, glass and reinforced concrete and basic geometric shapes. A circular drum-like ticket hall of brick and glass panels rises from a low single storey structure and is capped by a flat concrete roof. The design was inspired by Gunnar Asplund's design of the Stockholm City Library.

The centre of the ticket hall is occupied by a disused ticket office (a passimeter in London Underground parlance) which houses an exhibition on the station and the line. Like Holden's other stations on the extension, Arnos Grove is a Grade II listed building. The building features as one of the 12 "Great Modern Buildings" profiled in The Guardian during October 2007 and was summarised by architectural critic Jonathan Glancey as "...truly what German art historians would describe as a gesamtkunstwerk, a total and entire work of art." (Full article...)

Selected articles 46

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/46

Once on the ground, confusion over check lists led to an explosion in the port wing whilst the crew were evacuating passengers followed by a major fire which killed five of the 127 on board. The actions taken by those involved in the accident resulted in the award of a George Cross, a British Empire Medal and an MBE. As a direct result of the accident, BOAC changed the check lists for engine severe failures and engine fires, combining them both into one check list. (Full article...)

Selected articles 47

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/47

AJS Group was wound-up in 1991 and the two subsidiaries were taken over by Lynton Travel Group and Blazefield Group. Both companies expanded their operations and acquired new routes, but the former LCNE routes passed through a series of owners before they each ended up under the control of Arriva Southern Counties by 2005. (Full article...)

Selected articles 48

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/48

The line was upgraded in 1894 and rebuilt in 1910 by the Metropolitan Railway which introduced more advanced locomotives, allowing trains to run faster. The population of the area remained low, and the primary income remained goods to and from farms. Between 1899 and 1910 other lines were built in the area, providing more direct services to London and the north of England. The Brill Tramway went into financial decline.

In 1933 the Metropolitan Railway became part of London Transport. The Brill Tramway became part of the London Underground, despite being 40 miles (65 km) from London and not being underground. Seeing little possibility that the line could become a viable passenger route, London Transport closed the Brill Tramway in 1935. Little trace remains other than the former junction station at Quainton Road, now the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre. (Full article...)

Selected articles 49

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/49

Originally built with two platforms and a capacity for up to six lifts, the station was never fully completed. Suffering from low passenger numbers, one platform was taken out of use before the First World War and the station and branch were considered for closure several times, but survived as a weekday peak hours only service until closed in 1994, when the cost of replacing the lifts at Aldwych was considered too high compared to the income generated. The station has long been popular as a filming location and has appeared as itself and as other London Underground stations in a variety of films. (Full article...)

Selected articles 50

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/50

Located 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) west of Central London, flying at Heathrow began in World War I when a military airfield was laid out to the south-east of the hamlet that gives the airport its name. In the years preceding World War II, the airfield was used for manufacturing and testing by the Fairey Aviation Company. It was requisitioned by the government in 1943 for expansion as a RAF base although it saw little use as such. After the war it became a civilian airport with the first flight on 1 January 1946.

In its early days Heathrow had as many as six short runways arranged as a star, but now has two parallel main runways spanning east-to-west and five operational terminals. In January 2009 a controversial third runway was approved by the UK government, but this was cancelled in May 2010 following a change of government. (Full article...)

Selected articles 51

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/51

.png.webp)

The scheme applies to diesel engine vehicles over 1.205 tonnes, which must be registered with TfL. The scheme does not affect cars or motorcycles. Owners of vehicles that do not meet these requirements must pay a fee of up to £200 with failure to pay resulting in a fine. A limited range of vehicles are exempted or able to obtain a discount from the charge. Payment of the LEZ charge is in addition to any congestion charge required.

Like the congestion charge, the zone is monitored using Automatic Number Plate Reading Cameras to record number plates. Vehicles entering or moving within the zone are checked against the records of the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency to enable TfL to pursue vehicles that have not paid. (Full article...)

Selected articles 52

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/52

The UERL struggled financially in its first years and narrowly avoided bankruptcy in 1908. A policy of expansion by acquisition was followed before World War I, so that the company came to operate the majority of the underground railway lines in and around London. It also controlled large bus and tram fleets, the profits from which subsidised the financially weaker railways. After the war, railway extensions took the UERL's services out into suburban areas to stimulate additional passenger numbers, so that, by the early 1930s, the company's lines stretched beyond the County of London encouraging the rapid expansion of the city.

In the 1920s, competition from unregulated bus operators reduced the profitability of the road transport operations, leading the UERL's directors to seek government regulation. This led to the establishment of the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933, which absorbed the UERL and all of the independent and municipally operated railway, bus and tram services in the London area. (Full article...)

Selected articles 53

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/53

.jpg.webp)

The company failed to gain a monopoly of the burial industry, and the scheme was not as successful as its promoters had hoped. While they had planned to carry between 10,000 and 50,000 bodies per year, in 1941 after 87 years of operation only slightly over 200,000 burials had been conducted in Brookwood Cemetery. On the night of 16–17 April 1941 the London terminus was badly damaged in an air raid and was rendered unusable. The London Necropolis Railway was never used again and soon after the end of the Second World War the surviving parts of the London station were sold as office space, and the rail tracks and stations in the cemetery were removed. (Full article...)

Selected articles 54

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/54

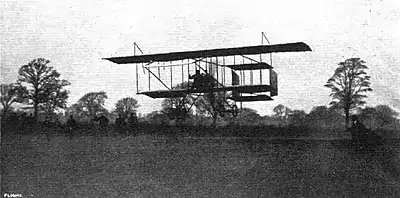

The first to make the attempt was Claude Grahame-White, an Englishman from Hampshire. He took off from London on 23 April 1910, and made his first planned stop at Rugby. His biplane subsequently suffered engine problems, forcing him to land again, near Lichfield. High winds made it impossible for Grahame-White to continue his journey, and his aeroplane suffered further damage on the ground when it was blown over.

While Grahame-White's aeroplane was being repaired in London, late on 27 April Paulhan took off, heading for Lichfield. A few hours later Grahame-White was made aware of Paulhan's departure, and immediately set off in pursuit. The next morning, after an unprecedented night-time take-off, he almost caught up with Paulhan, but his aeroplane was overweight and he was forced to concede defeat. Paulhan reached Manchester early on 28 April, winning the challenge. Both aviators celebrated his victory at a special luncheon held at the Savoy Hotel in London.

The event marked the first long-distance aeroplane race in England, the first take-off of a heavier-than-air machine at night, and the first powered flight into Manchester from outside the city. Paulhan repeated the journey in April 1950, the fortieth anniversary of the original flight, this time as a passenger aboard a British jet fighter. (Full article...)

Selected articles 55

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/55

The railway was soon extended from both ends and northwards via a branch from Baker Street. It reached Hammersmith in 1864, Richmond in 1877 and completed the Inner Circle in 1884, but the most important route became the line north into the Middlesex countryside, where it stimulated the development of new suburbs. Harrow was reached in 1880, and the line eventually extended as far as Verney Junction in Buckinghamshire, more than 50 miles (80 kilometres) from Baker Street and the centre of London.

Electric traction was introduced in 1905 and by 1907 electric multiple units operated most of the services, though electrification of outlying sections did not occur until decades later. Unlike other railway companies in the London area, the Met developed land for housing and after World War I promoted housing estates near the railway with the "Metro-land" brand. On 1 July 1933, the Metropolitan Railway was amalgamated with the underground railways of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London and the capital's tramway and bus operators to form the London Passenger Transport Board.

Today, former Metropolitan Railway tracks and stations are used by the London Underground's Metropolitan, Circle, District, Hammersmith & City, Piccadilly and Jubilee lines, and by Chiltern Railways. (Full article...)

Selected articles 56

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/56

The tunnel was originally opened as a single bore in 1897 by the then Prince of Wales, as a major transport project to improve commerce and trade in London's East End. By the 1930s, capacity was becoming inadequate, and a second bore opened in 1967, handling southbound traffic while the earlier 19th century tunnel handled northbound.

The tunnel is a key link for both local and longer-distance traffic between the north and south sides of the river. It is the easternmost free fixed road crossing of the Thames, and regularly suffers congestion, to the extent that tidal flow schemes were in place from 1978 until controversially removed in 2007. Proposals to solve the traffic problems have included building a third bore, constructing alternative crossings of the Thames such as the now cancelled Thames Gateway Bridge or the Silvertown Tunnel, and providing better traffic management, particularly for heavy goods vehicles. (Full article...)

Selected articles 57

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/57

Part of the eastern section, between Liverpool Street and Shenfield in Essex, was transferred to a precursor service called TfL Rail in 2015; this section will be connected to the core through central London to Paddington from May 2019. The western section, from Paddington to Heathrow Airport and Reading in Berkshire, is due to open in December 2019, completing the new east–west route across London and providing a new high-frequency commuter and suburban passenger service.

The project was approved in 2007 and construction began in 2009 on the central section and connections to existing lines that will become part of the route. With a budget of £14.8 billion, it is Europe's largest infrastructure construction project. Its main feature is 21 km (13 mi) of new twin tunnels below central London running from Paddington to Stratford and Canary Wharf in the east. An almost entirely new line will branch from the main line at Whitechapel to Canary Wharf, crossing under the River Thames, with a new station at Woolwich and connecting with the North Kent Line at the Abbey Wood terminus.

Trains will run at frequencies in the central section of up to 24 trains per hour in each direction. It is expected to relieve pressure on existing east-west London Underground lines such as the Central and District lines, as well as the Jubilee line extension and the Heathrow branch of the Piccadilly line. The need for extra capacity along this corridor is such that the former head of TfL, Sir Peter Hendy, predicted that the Crossrail lines will be "immediately full" as soon as they open. Crossrail will be operated by MTR Corporation (Crossrail) Ltd as a London Rail concession of Transport for London, in a similar manner to London Overground. (Full article...)

Selected articles 58

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/58

In 1912, the LGOC was bought by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) which operated much of the London Underground to broaden its control of transport in the city. In 1933, the UERL and the LGOC became part of the new London Passenger Transport Board when transport services in the capital were merged. The name London General fell into disuse, and London Transport instead became synonymous with the red London bus.

Selected articles 59

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/59

Bicycles are available to hire from docking stations located around the city with the first 30 minutes of use free of charge. The bicycles are manufactured by Cycles Devinci in Canada and are designed to be robust and vandal resistant with puncture resistant tyres, chain guards and LED lighting and cabling built into the frames.

Selected articles 60

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/60

The crash forced the first carriage into the roof of the tunnel at the front and back, but the middle remained on the trackbed; the 16-metre-long (52 ft) coach was crushed to 6.1 metres (20 ft). The second carriage was concertinaed at the front as it collided with the first, and the third rode over the rear of the second. The brakes were not applied and the dead man's handle was still depressed when the train crashed. It took 13 hours for emergency services to remove the injured from the wreckage, many of whom had to be cut free. Poor ventilation caused temperatures in the tunnel to rise to over 49 °C (120 °F). It took a further four days to extract the last body, that of Newson; his cab, normally 91 centimetres (3 ft) deep, had been crushed to 15 centimetres (6 in).

The post-mortem on Newson showed no medical reason to explain the crash. A cause has never been established, and theories include suicide, that he may have been distracted, or that he was affected by conditions such as transient global amnesia or akinesis with mutism. Tests showed that Newson had a blood alcohol level of 80 mg/100 ml—the level at which one can be prosecuted for drink driving, though the alcohol may have been produced by the natural decomposition process over four days at a high temperature.

Following the crash, London Underground introduced a safety system that automatically stops a train when travelling too fast. This became known informally as Moorgate protection.

Selected articles 61

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/61

It is one of the busiest of the British motorway network: 196,000 vehicles were recorded on a busy day near Heathrow Airport in 2003 and the western half experienced an average daily flow of 147,000 vehicles in 2007. To alleviate congestion, sections of the motorway have been widened from the original three-lane carriageways to four-, five- or six-lane carriageways. Other sections use Smart motorway operation with hard shoulders replaced with standard lanes.

The M25, plus the short non-motorway A282 which joins the two ends of the M25 across the River Thames using the Dartford Crossing, is Europe's second longest orbital road after the Berliner Ring, which is 122 miles (196 km).

Selected articles 62

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/62

The LPTB was set up by the London Passenger Transport Act 1933 enacted on 13 April 1933. The bill had been introduced by Herbert Morrison, who was Transport Minister in the Labour Government until 1931, but was passed during the subsequent coalition government. On 1 July 1933, the LPTB came into being to manage the "London Passenger Transport Area” within which it had almost complete authority over the operation of local transport services.

Led by Lord Ashfield and Frank Pick, who had previously run the Underground Group, the LPTB took over the operations of ninety-two bus, tram, trolley bus and train companies. The LPTB embarked on a £35 million capital investment programme that extended services and reconstructed many existing assets, mostly under the umbrella of the 1935–1940 "New Works Programme which delivered extensions to the Central, Bakerloo, Northern and Metropolitan lines; new trains and maintenance depots; extensive rebuilding of many central area stations and the replacement of trams with trolley buses.

Selected articles 63

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/63

Built in Greenock, Scotland, in 1865, Princess Alice was employed for two years in Scotland before being purchased by the Waterman's Steam Packet Co to carry passengers on the Thames. By 1878 she was owned by the London Steamboat Co and was captained by William R. H. Grinstead; the ship carried passengers on a stopping service from Swan Pier, near London Bridge, downstream to Sheerness, Kent, and back. On her homeward journey, at an hour after sunset on 3 September 1878, she passed Tripcock Point and entered Gallions Reach, she took the wrong sailing line and was hit by Bywell Castle; the point of the collision was the area of the Thames where 75 million imperial gallons (340,000 m3) of London's raw sewage had just been released. Princess Alice broke into three parts and sank quickly; her passengers drowned in the heavily polluted waters.

Selected articles 64

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/64

.jpg.webp)

Selected articles 65

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/65

Marchioness had been hired for the evening for a birthday party and had about 130 people on board, four of whom were crew and bar staff. Both vessels were heading downstream, against the tide, Bowbelle travelling faster than the smaller vessel. Although the exact paths taken by the ships, and the precise series of events and their locations, are unknown, the subsequent inquiry considered it likely that Bowbelle struck Marchioness from the rear, causing the latter to turn to port, where she was hit again, then pushed along, turning over and being pushed under Bowbelle's bow. It took thirty seconds for Marchioness to sink; 24 bodies were found within the ship when it was raised.

Selected articles 66

Portal:London transport/Selected articles/66

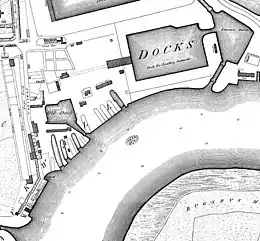

The Blackwall Rock was a reef in the River Thames near Blackwall in East London at short distance upstream from Blackwall Stairs and between the entrances of the West and East India Docks. The rock provided a useful shelter for moored vessels, but also proved a hazardous obstruction to river navigation as it was sometimes less than 3 feet (1 m) below the surface at low tide.

The entrance to the West India Docks, just to the south-west of the rock, was substantially obstructed by the reef upon the docks' opening in 1802. In 1803, Robert Edington surveyed the rock estimated its dimensions as 600 by 150 feet (183 m × 46 m). An 1846 report by the Tidal Harbours Commission described it as an outcrop of plum-pudding stone.

Early attempts to break the rock with explosives were largely unsuccessful. William Jessop was engaged by Trinity House to undertake the rock's removal which he did using a chisel, operated from a barge much as with pile driving. This method successfully reduced the height of the rock by 15 feet (4.6 m), after which a cylindrical coffer dam was employed to allow workers' access to remove rubble.