| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sibelium, others |

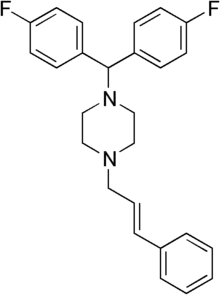

| Other names | 1-[bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-4-cinnamyl-piperazine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | >99% |

| Metabolism | Mainly CYP2D6 |

| Metabolites | ≥15 |

| Elimination half-life | 5–15 hrs (single dose) 18–19 days (multiple doses) |

| Excretion | Feces, <1% urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.052.652 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C26H26F2N2 |

| Molar mass | 404.505 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 251.5 °C (484.7 °F) (dihydrochloride) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Flunarizine, sold under the brand name Sibelium among others, is a drug classified as a calcium antagonist which is used for various indications.[1] It is not available by prescription in the United States or Japan. The drug was discovered at Janssen Pharmaceutica (R14950) in 1968.

Medical uses

Flunarizine is effective in the prophylaxis of migraine,[2] occlusive peripheral vascular disease, vertigo of central and peripheral origin,[3] and as an add-on in the treatment of epilepsy where its effect is weak and not recommended.[4] It has been shown to significantly reduce headache frequency and severity in both adults and children.

Contraindications

Flunarizine is contraindicated in patients with depression, in the acute phase of a stroke, and in patients with extrapyramidal symptoms or Parkinson's disease.[5] It is also contraindicated in hypotension, heart failure and arrhythmia.

Side effects

Common side effects include drowsiness (20% of patients), weight gain (10%), as well as extrapyramidal effects and depression in elderly patients.[3]

In a systematic review of the literature about cinnarizine- and flunarizine-associated movement disorders. The authors found one hundred seventeen reports containing 1920 individuals who developed an abnormal movement secondary to these drugs. The movement disorders encountered were parkinsonism, dyskinesias, akathisia, dystonia, myoclonus, extrapyramidal symptoms, tremors, bradykinesia, and myokymia.[6]

Interactions

The effects of other sedating drugs and alcohol, as well as antihypertensives, can be increased. No relevant pharmacokinetic interactions have been described.[3][5]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Flunarizine is a selective calcium antagonist with moderate other actions including antihistamine, serotonin receptor blocking and dopamine D2 blocking activity. Compared to other calcium channel blockers such as dihydropyridine derivatives, verapamil and diltiazem, flunarizine has low affinity to voltage-dependent calcium channels. It has been theorised that it may act not by inhibiting calcium entry into cells, but rather by an intracellular mechanism such as antagonising calmodulin, a calcium binding protein.[3]

Pharmacokinetics

Flunarizine is well absorbed (>80%) from the gut and reaches maximal blood plasma concentrations after two to four hours, with more than 99% of the substance bound to plasma proteins. It readily passes the blood–brain barrier. When given daily, a steady state is reached after five to eight weeks. Concentrations in the brain are about ten times higher than in the plasma.[3][5]

It is metabolised in the liver, mainly by the enzyme CYP2D6. At least 15 different metabolites are described, including (in animals) N-desalkyl and hydroxy derivatives and glucuronides. Less than 1% is excreted in unchanged form, and the main excretion path is via bile and faeces. Elimination half life varies widely between individuals and is about 5 to 15 hours after a single dose, and 18 to 19 days on average when given daily.[3][5]

Chemistry

Flunarizine is a diphenylmethylpiperazine derivative related to the antihistamines hydroxyzine and cinnarizine (an older molecule also discovered by Janssen).

Research

Flunarizine may help to reduce the severity and duration of attacks of paralysis associated with the more serious form of alternating hemiplegia, as well as being effective in rapid onset dystonia-parkinsonism (RDP). Both these conditions arise from specific mutations in the ATP1A3 gene.[7][8]

Flunarizine extended motor neuron survival in spinal cord, protected skeletal muscles from cell death and atrophy and extended survival by 40% in an animal model of spinal muscular atrophy.[9] Flunarizine has also shown promise as an anti-prion medication.

References

- ↑ Fagbemi O, Kane KA, McDonald FM, Parratt JR, Rothaul AL (September 1984). "The effects of verapamil, prenylamine, flunarizine and cinnarizine on coronary artery occlusion-induced arrhythmias in anaesthetized rats". British Journal of Pharmacology. 83 (1): 299–304. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb10146.x. PMC 1987188. PMID 6487894.

- ↑ Amery WK (March 1983). "Flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker: a new prophylactic drug in migraine". Headache. 23 (2): 70–74. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2302070.x. PMID 6343298. S2CID 36940918.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dinnendahl V, Fricke U, eds. (2012). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ↑ Hasan M, Pulman J, Marson AG (March 2013). "Calcium antagonists as an add-on therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (3): CD002750. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002750.pub2. PMC 7100543. PMID 23543516.

- 1 2 3 4 Haberfeld H, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag.

- ↑ Rissardo JP, Caprara AL (December 2020). "Cinnarizine- and flunarizine-associated movement disorder: a literature review". The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery. 56 (1). doi:10.1186/s41983-020-00197-w. ISSN 1687-8329.

- ↑ Brashear A, Sweadner KJ, Cook JF, Swoboda KJ, Ozelius L (1993). "ATP1A3-Related Neurologic Disorders". GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301294.

- ↑ Kansagra S, Mikati MA, Vigevano F (2013). "Alternating hemiplegia of childhood". Pediatric Neurology Part II. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 112. pp. 821–6. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52910-7.00001-5. ISBN 9780444529107. PMID 23622289.

- ↑ Sapaly D, Dos Santos M, Delers P, Biondi O, Quérol G, Houdebine L, et al. (February 2018). "Small-molecule flunarizine increases SMN protein in nuclear Cajal bodies and motor function in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 2075. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.2075S. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20219-1. PMC 5794986. PMID 29391529.

- Therapeutic Choices, sixth edition, Canadian Pharmacists Association, 2011.