| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans in the United States |

|---|

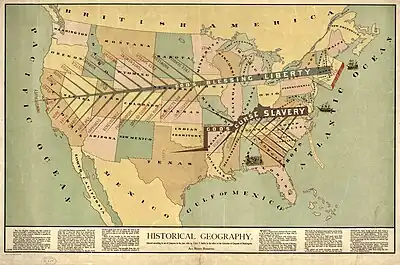

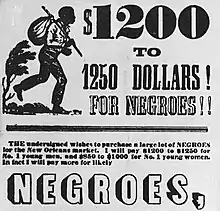

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom.[1] In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

By the time of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the status of enslaved people had been institutionalized as a racial caste associated with African ancestry.[2] During and immediately following the Revolution, abolitionist laws were passed in most Northern states and a movement developed to abolish slavery. The role of slavery under the United States Constitution (1789) was the most contentious issue during its drafting. Although the creators of the Constitution never used the word "slavery", the final document, through the Three-Fifths Clause, gave slave owners disproportionate political power by augmenting the congressional representation and the Electoral College votes of slaveholding states.[3] The Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution—Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3—provided that, if a slave escaped to another state, the other state had to return the slave to his or her master. This clause was implemented by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, passed by Congress. All Northern states had abolished slavery in some way by 1805; sometimes at a future date, sometimes with an intermediary status of unpaid indentured servent. Abolition was in many cases a very gradual process; a few hundred people were enslaved in the Northern states as late as the 1840 census. Some slaveowners, primarily in the Upper South, freed their slaves, and philanthropists and charitable groups bought and freed others. The Atlantic slave trade was outlawed by individual states beginning during the American Revolution. The import trade was banned by Congress in 1808, the earliest date the Constitution permitted (Article 1, Section 9), although smuggling was common thereafter.[4][5] It has been estimated that before 1820 a majority of serving congressmen owned slaves, and that about 30 percent of congressmen who were born before 1840 (some of whom served into the 20th century) at some time in their lives, were owners of slaves.[6]

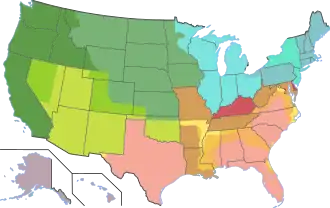

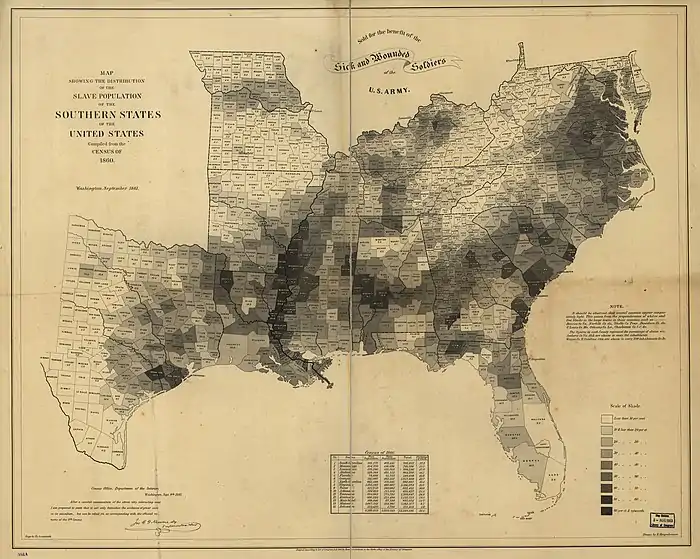

The rapid expansion of the cotton industry in the Deep South after the invention of the cotton gin greatly increased demand for slave labor, and the Southern states continued as slave societies. The United States, divided into slave and free states, became ever more polarized over the issue of slavery. Driven by labor demands from new cotton plantations in the Deep South, the Upper South sold more than a million slaves who were taken to the Deep South. The total slave population in the South eventually reached four million.[7][8] As the United States expanded, the Southern states attempted to extend slavery into the new Western territories to allow proslavery forces to maintain their power in Congress. The new territories acquired by the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican Cession were the subject of major political crises and compromises.[9] By 1850, the newly rich, cotton-growing South was threatening to secede from the Union, and tensions continued to rise. Bloody fighting broke out over slavery in the Kansas Territory. Slavery was defended in the South as a "positive good", and the largest religious denominations split over the slavery issue into regional organizations of the North and South.

When Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election on a platform of halting the expansion of slavery, seven slave states seceded to form the Confederacy. Shortly afterward, on April 12, 1861, the Civil War began when Confederate forces attacked the U.S. Army's Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Four additional slave states then joined the Confederacy after Lincoln, on April 15, called forth in response called up the militia to suppress the rebellion.[10] During the war some jurisdictions abolished slavery and, due to Union measures such as the Confiscation Acts and the Emancipation Proclamation, the war effectively ended slavery in most places. After the Union victory, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865, prohibiting "slavery [and] involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime."[11]

Background

During most of the British colonial period, slavery existed in all the colonies. People enslaved in the North typically worked as house servants, artisans, laborers and craftsmen, with the greater number in cities. Many men worked on the docks and in shipping. In 1703, more than 42 percent of New York City households held enslaved people in bondage, the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies, behind only Charleston, South Carolina.[12] Enslaved people were also used as agricultural workers in farm communities, especially in the South, but also in upstate New York and Long Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey. By 1770, there were 397,924 blacks out of a population of 2.17 million in what would soon become the United States. The slaves of the colonial era were unevenly distributed: 14,867 lived in New England, where they were three percent of the population; 34,679 lived in the mid-Atlantic colonies, where they were six percent of the population; and 347,378 in the five Southern Colonies, where they were 31 percent of the population.[13]

The South developed an agricultural economy dependent on commodity crops. Its planters rapidly acquired a significantly higher number and proportion of enslaved people in the population overall, as its commodity crops were labor-intensive.[14] Early on, enslaved people in the South worked primarily on farms and plantations growing indigo, rice and tobacco (cotton did not become a major crop until after the 1790s). In 1720, about 65 percent of South Carolina's population was enslaved.[15] Planters (defined by historians in the Upper South as those who held 20 or more slaves) used enslaved workers to cultivate commodity crops. They also worked in the artisanal trades on large plantations and in many Southern port cities. The later wave of settlers in the 18th century who settled along the Appalachian Mountains and backcountry were backwoods subsistence farmers, and they seldom held enslaved people.

Beginning in the second half of the 18th century, a debate emerged over the continued importation of African slaves to the American colonies. Many in the colonies, including the Southern slavocracy, opposed further importation of slaves due to fears that it would destabilize colonies and lead to further slave rebellions. In 1772, prominent Virginians submitted a petition to the Crown, requesting that the slave trade to Virginia be abolished; it was rejected.[16] Rhode Island forbade the importation of slaves in 1774. The influential revolutionary Fairfax Resolves called for an end to the "wicked, cruel and unnatural" Atlantic slave trade.[17] All of the colonies banned slave importations during the Revolutionary War.[18]

Slavery in the American Revolution and early republic

As historian Christopher L. Brown put it, slavery "had never been on the agenda in a serious way before", but the American Revolution "forced it to be a public question from there forward".[19][20]

After the new country's independence was secure, slavery was a topic of contention at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Many of Founding Fathers of the United States were plantation owners who owned large numbers of enslaved laborers; the original Constitution preserved their right to own slaves, and they further gained a political advantage in owning slaves. Although the enslaved of the early Republic were considered sentient property, were not permitted to vote, and had no rights to speak of, they were to be enumerated in population censuses and counted as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of representation in the national legislature, the U.S. Congress.

Slaves and free blacks who supported the Continental Army

The rebels began to offer freedom as an incentive to motivate slaves to fight on their side. Washington authorized slaves to be freed who fought with the American Continental Army. Rhode Island started enlisting slaves in 1778, and promised compensation to owners whose slaves enlisted and survived to gain freedom.[22][23] During the course of the war, about one-fifth of the Northern army was black.[24] In 1781, Baron Closen, a German officer in the French Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment at the Battle of Yorktown, estimated the American army to be about one-quarter black.[25] These men included both former slaves and free-born blacks. Thousands of free blacks in the Northern states fought in the state militias and Continental Army. In the South, both sides offered freedom to slaves who would perform military service. Roughly 20,000 slaves fought in the American Revolution.[21][26][27][28][29]

Black Loyalists

After the Revolutionary War broke out, the British realized they lacked the manpower necessary to prosecute the war. In response, British commanders began issuing proclamations to Patriot-owned slaves, offering freedom if they fled to British lines and assisted the British war effort.[30] Such proclamations, which were repeatedly issued over the course of the conflict, which resulted in up to 100,000 American slaves fleeing to British lines.[31] Self-emancipated slaves who reached British lines were organized into a variety of military units which served in all theaters of the war. Formerly enslaved women and children, in lieu of military service, worked instead as laborers and domestic servants. At the end of the war, freed slaves in British lines either evacuated to other British colonies or to Britain itself, were re-enslaved by the victorious Americans or fled into the countryside.[32]

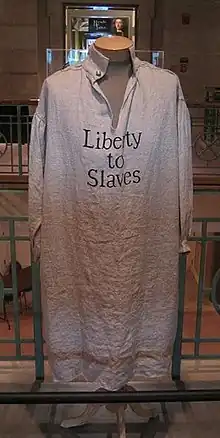

In early 1775, the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth of his intention to free slaves owned by American Patriots in case they staged a rebellion.[33][34] On November 7, 1775, Dunmore issued Dunmore's Proclamation, which and promised freedom to any slaves of American patriots who would leave their masters and join the British forces.[35] Historians agree that the proclamation was chiefly designed for practical rather than moral reasons, and slaves owned by American Loyalists were unaffected by the proclamation. About 1,500 slaves owned by patriots escaped and joined Dunmore's forces. A total of 18 slaves fled George Washington's plantation, one of whom, Harry, served in Dunmore's all-black loyalist regiment called "the Black Pioneers."[36] Escapees who joined Dunmore had "Liberty to Slaves" stitched on to their jackets.[37] Most died of disease before they could do any fighting, but three hundred of these freed slaves made it to freedom in Britain.[38] Historian Jill Lepore writes that "between eighty and a hundred thousand (nearly one in five black slaves) left their homes ... betting on British victory", but Cassandra Pybus states that between 20,000 and 30,000 is a more realistic number of slaves who defected to the British side during the war.[36]

Many slaves took advantage of the disruption of war to escape from their plantations to British lines or to fade into the general population. Upon their first sight of British vessels, thousands of slaves in Maryland and Virginia fled from their owners.[39]: 21 Throughout the South, losses of slaves were high, with many due to escapes.[40] Slaves also escaped throughout New England and the mid-Atlantic, with many joining the British who had occupied New York.[36] In the closing months of the war, the British evacuated freedmen and also removed slaves owned by loyalists. Around 15,000 black loyalists left with the British, most of them ending up as free people in England or its colonies.[41] Washington hired a slave catcher during the war, and at its end he pressed the British to return the slaves to their masters.[36] With the British certificates of freedom in their belongings, the black loyalists, including Washington's slave Harry, sailed with their white counterparts out of New York harbor to Nova Scotia.[36] More than 3,000 were resettled in Nova Scotia, where they were eventually granted land and formed the community of the black Nova Scotians.

Early abolitionism in the United States

In the first two decades after the American Revolution, state legislatures and individuals took actions to free slaves. Northern states passed new constitutions that contained language about equal rights or specifically abolished slavery; some states, such as New York and New Jersey, where slavery was more widespread, passed laws by the end of the 18th century to abolish slavery incrementally. By 1804, all the Northern states had passed laws outlawing slavery, either immediately or over time. In New York, the last slaves were freed in 1827 (celebrated with a big July 5 parade). Indentured servitude, which had been widespread in the colonies (half the population of Philadelphia had once been indentured servants), dropped dramatically, and disappeared by 1800. However, there were still forcibly indentured servants in New Jersey in 1860. No Southern state abolished slavery, but some individual owners, more than a handful, freed their slaves by personal decision, often providing for manumission in wills but sometimes filing deeds or court papers to free individuals. Numerous slaveholders who freed their slaves cited revolutionary ideals in their documents; others freed slaves as a promised reward for service. From 1790 to 1810, the proportion of blacks free in the United States increased from 8 to 13.5 percent, and in the Upper South from less than one to nearly ten percent as a result of these actions.[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51]

Starting in 1777, the rebels outlawed the importation of slaves state by state. They all acted to end the international trade, but, after the war, it was reopened in North Carolina (opened until 1794) and Georgia (opened until 1798) and South Carolina (opened until 1787, and then reopened again in 1803.)[52] In 1807, the United States Congress acted on President Thomas Jefferson's advice and, without controversy, made importing slaves from abroad a federal crime, effective the first day that the United States Constitution permitted this prohibition: January 1, 1808.[53]

During the Revolution and in the following years, all states north of Maryland took steps towards abolishing slavery. In 1777, the Vermont Republic, which was still unrecognized by the United States, passed a state constitution prohibiting slavery. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society, led in part by Benjamin Franklin, was founded in 1775, and Pennsylvania began gradual abolition in 1780. In 1783, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled in Commonwealth v. Jennison that slavery was unconstitutional under the state's new 1780 constitution. New Hampshire began gradual emancipation in 1783, while Connecticut and Rhode Island followed suit in 1784. The New York Manumission Society, which was led by John Jay, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, was founded in 1785. New York state began gradual emancipation in 1799, and New Jersey did the same in 1804.

Shortly after the Revolution, the Northwest Territory was established, by Manasseh Cutler and Rufus Putnam (who had been George Washington's chief engineer). Both Cutler and Putnam came from Puritan New England. The Puritans strongly believed that slavery was morally wrong. Their influence on the issue of slavery was long-lasting, and this was provided significantly greater impetus by the Revolution. The Northwest Territory (which became Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota) doubled the size of the United States, and it was established at the insistence of Cutler and Putnam as "free soil" – no slavery. This was to prove crucial a few decades later. Had those states been slave states, and their electoral votes gone to Abraham Lincoln's main opponent, Lincoln would not have become president. The Civil War would not have been fought. Even if it eventually had been, the North might well have lost.[54][55][56][57]

Constitution of the United States

.jpg.webp)

Slavery was a contentious issue in the writing and approval of the Constitution of the United States.[58] The words "slave" and "slavery" did not appear in the Constitution as originally adopted, although several provisions clearly referred to slaves and slavery. Until the adoption of the 13th Amendment in 1865, the Constitution did not prohibit slavery.[59]

Section 9 of Article I forbade the federal government from prohibiting the importation of slaves, described as "such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit", for twenty years after the Constitution's ratification (until January 1, 1808). The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Thomas Jefferson (who had called for its enactment in his 1806 State of the Union address), went into effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date on which the importation of slaves could be prohibited under the Constitution.[60]

The delegates approved the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution (Article IV, section 2, clause 3), which prohibited states from freeing slaves who fled to them from another state and required that they be returned to their owners.[61] The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 gave effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause.[62] Salmon P. Chase considered the Fugitive Slave Acts unconstitutional because "The Fugitive Slave Clause was a compact among the states, not a grant of power to the federal government".[63]

Three-fifths Compromise

.jpg.webp)

In a section negotiated by James Madison of Virginia, Section 2 of Article I designated "other persons" (slaves) to be added to the total of the state's free population, at the rate of three-fifths of their total number, to establish the state's official population for the purposes of apportionment of congressional representation and federal taxation.[64] The "Three-Fifths Compromise" was reached after a debate in which delegates from Southern (slaveholding) states argued that slaves should be counted in the census just as all other persons were while delegates from Northern (free) states countered that slaves should not be counted at all. The compromise strengthened the political power of Southern states, as three-fifths of the (non-voting) slave population was counted for congressional apportionment and in the Electoral College, although it did not strengthen Southern states as much as it would have had the Constitution provided for counting all persons, whether slave or free, equally.

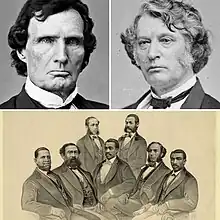

In addition, many parts of the country were tied to the Southern economy. As the historian James Oliver Horton noted, prominent slaveholder politicians and the commodity crops of the South had a strong influence on United States politics and economy. Horton said,

in the 72 years between the election of George Washington and the election of Abraham Lincoln, 50 of those years [had] a slaveholder as president of the United States, and, for that whole period of time, there was never a person elected to a second term who was not a slaveholder.[65]

The power of Southern states in Congress lasted until the Civil War, affecting national policies, legislation, and appointments.[65] One result was that most of the justices appointed to the Supreme Court were slave owners. The planter elite dominated the Southern congressional delegations and the United States presidency for nearly fifty years.[65]

Slavery in the 19th century

Slavery in the United States was a variable thing, in "constant flux, driven by the violent pursuit of ever-larger profits."[66] According to demographic calculations by J. David Hacker of the University of Minnesota, approximately four out of five of all of the slaves who ever lived in the United States or the territory that became the United States (beginning in 1619 and including all colonies that were eventually acquired or conquered by the United States) were born in or imported to the United States in the 19th century.[67] Slaves were the labor force of the South, but slave ownership was also the foundation upon which American white supremacy was constructed. Historian Walter Johnson argues that "one of the many miraculous things a slave could do was make a household white...", meaning that the value of whiteness in America was in some ways measured by the ability to purchase and maintain black slaves.[68]

Harriet Beecher Stowe described slavery in the United States in 1853:[69]

What, then, is American slavery, as we have seen it exhibited by law, and by the decision of Courts? Let us begin by stating what it is not:

1. It is not apprenticeship.

2. It is not guardianship.

3. It is in no sense a system for the education of a weaker race by a stronger.

4. The happiness of the governed is in no sense its object.

5. The temporal improvement or the eternal well-being of the governed is in no sense its object.

The object of it has been distinctly stated in one sentence by Judge Ruffin,— "The end is the profit of the master, his security, and the public safety."

Slavery, then, is absolute despotism, of the most unmitigated form.

Justifications in the South

American slavery as "a necessary evil"

In the 19th century, proponents of slavery often defended the institution as a "necessary evil". At that time, it was feared that emancipation of black slaves would have more harmful social and economic consequences than the continuation of slavery. On April 22, 1820, Thomas Jefferson, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, wrote in a letter to John Holmes, that with slavery,

We have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.[73]

The French writer and traveler Alexis de Tocqueville, in his influential Democracy in America (1835), expressed opposition to slavery while observing its effects on American society. He felt that a multiracial society without slavery was untenable, as he believed that prejudice against blacks increased as they were granted more rights (for example, in Northern states). He believed that the attitudes of white Southerners, and the concentration of the black population in the South, were bringing the white and black populations to a state of equilibrium, and were a danger to both races. Because of the racial differences between master and slave, he believed that the latter could not be emancipated.[74]

In a letter to his wife dated December 27, 1856, in reaction to a message from President Franklin Pierce, Robert E. Lee wrote,

There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil. It is idle to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it is a greater evil to the white than to the colored race. While my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more deeply engaged for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, physically, and socially. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their further instruction as a race, and will prepare them, I hope, for better things. How long their servitude may be necessary is known and ordered by a merciful Providence.[75][76]

American slavery as "a positive good"

However, as the abolitionist movement's agitation increased and the area developed for plantations expanded, apologies for slavery became more faint in the South. Leaders then described slavery as a beneficial scheme of labor management. John C. Calhoun, in a famous speech in the Senate in 1837, declared that slavery was "instead of an evil, a good – a positive good". Calhoun supported his view with the following reasoning: in every civilized society one portion of the community must live on the labor of another; learning, science, and the arts are built upon leisure; the African slave, kindly treated by his master and mistress and looked after in his old age, is better off than the free laborers of Europe; and under the slave system conflicts between capital and labor are avoided. The advantages of slavery in this respect, he concluded, "will become more and more manifest, if left undisturbed by interference from without, as the country advances in wealth and numbers".[81]

South Carolina army officer, planter, and railroad executive James Gadsden called slavery "a social blessing" and abolitionists "the greatest curse of the nation".[83] Gadsden was in favor of South Carolina's secession in 1850, and was a leader in efforts to split California into two states, one slave and one free.

Other Southern writers who also began to portray slavery as a positive good were James Henry Hammond and George Fitzhugh. They presented several arguments to defend the practice of slavery in the South.[84] Hammond, like Calhoun, believed that slavery was needed to build the rest of society. In a speech to the Senate on March 4, 1858, Hammond developed his "Mudsill Theory," defending his view on slavery by stating: "Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement. It constitutes the very mud-sill of society and of political government; and you might as well attempt to build a house in the air, as to build either the one or the other, except on this mud-sill." Hammond believed that in every class one group must accomplish all the menial duties, because without them the leaders in society could not progress.[84] He argued that the hired laborers of the North were slaves too: "The difference ... is, that our slaves are hired for life and well compensated; there is no starvation, no begging, no want of employment," while those in the North had to search for employment.[84]

George Fitzhugh used assumptions about white superiority to justify slavery, writing that, "the Negro is but a grown up child, and must be governed as a child." In The Universal Law of Slavery, Fitzhugh argues that slavery provides everything necessary for life and that the slave is unable to survive in a free world because he is lazy, and cannot compete with the intelligent European white race. He states that "The negro slaves of the South are the happiest, and in some sense, the freest people in the world."[85] Without the South, "He (slave) would become an insufferable burden to society" and "Society has the right to prevent this, and can only do so by subjecting him to domestic slavery."[85]

On March 21, 1861, Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy, delivered his Cornerstone Speech. He explained the differences between the Constitution of the Confederate States and the United States Constitution, laid out the cause for the American Civil War, as he saw it, and defended slavery:[86]

The new [Confederate] Constitution has put at rest forever all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institutions – African slavery as it exists among us – the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson, in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the "rock upon which the old Union would split." He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old Constitution were, that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with; but the general opinion of the men of that day was, that, somehow or other, in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away ... Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the idea of a Government built upon it – when the "storm came and the wind blew, it fell".

Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition.[86]

This view of the Negro "race" was backed by pseudoscience.[87] The leading researcher was Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright, inventor of the mental illnesses of drapetomania (the desire of a slave to run away) and dysaesthesia aethiopica ("rascality"), both cured by whipping. The Medical Association of Louisiana set up a committee, of which he was chair, to investigate "the Diseases and Physical Peculiarities of the Negro Race". Their report, first delivered to the Medical Association in an address, was published in their journal,[88] and then reprinted in part in the widely circulated DeBow's Review.[89]

Proposed expansion of slavery

Whether slavery was to be limited to the Southern states that already had it, or whether it was to be permitted in new states made from the lands of the Louisiana Purchase and Mexican Cession, was a major issue in the 1840s and 1850s. It was addressed by the Compromise of 1850 and during the Bleeding Kansas period.

Also relatively well-known are the proposals, including the Ostend Manifesto, to annex Cuba as a slave state, as well as the privately funded invasion of Cuba by Narciso López. There was also talk of making slave states of Mexico, Nicaragua (see Walker affair and Filibuster War) and other lands around the so-called Golden Circle. Less well-known today, though well-known at the time, is that pro-slavery Southerners:

- Actively sought to reopen the transatlantic slave trade[90]

- Funded illegal slave shipments from the Caribbean and Africa, such as the Wanderer slave shipment to Georgia in 1858[91]

- Wanted to reintroduce slavery in the Northern states, through federal action or Constitutional amendment making slavery legal nationwide, thus overriding state anti-slavery laws.[92][93] (See Crittenden Compromise.) This was described as "well underway" by 1858.[94]

- Said openly that slavery should by no means be limited to Negros, since in their view it was beneficial. Northern white workers, who were allegedly "wage slaves" already, would allegedly have better lives if they were enslaved.[95]

None of these ideas got very far, but they alarmed Northerners and contributed to the growing polarization of the country.

Abolitionism in the North

Slavery is a volcano, the fires of which cannot be quenched, nor its ravishes controlled. We already feel its convulsions, and if we sit idly gazing upon its flames, as they rise higher and higher, our happy republic will be buried in ruin, beneath its overwhelming energies.

Beginning during the Revolution and in the first two decades of the postwar era, every state in the North abolished slavery. These were the first abolitionist laws in the Atlantic World.[97][98] However, the abolition of slavery did not necessarily mean that existing slaves became free. In some states they were forced to remain with their former owners as indentured servants: free in name only, although they could not be sold and thus families could not be split, and their children were born free. The end of slavery did not come in New York until July 4, 1827, when it was celebrated (on July 5) with a big parade.[99] However, in the 1830 census, the only state with no slaves was Vermont. In the 1840 census, there were still slaves in New Hampshire (1), Rhode Island (5), Connecticut (17), New York (4), Pennsylvania (64), Ohio (3), Indiana (3), Illinois (331), Iowa (16), and Wisconsin (11). There were none in these states in the 1850 census.[100]

Most Northern states passed legislation for gradual abolition, first freeing children born to slave mothers (and requiring them to serve lengthy indentures to their mother's owners, often into their 20s as young adults). In 1845, the Supreme Court of New Jersey received lengthy arguments towards "the deliverance of four thousand persons from bondage".[101] Pennsylvania's last slaves were freed in 1847, Connecticut's in 1848, and while neither New Hampshire nor New Jersey had any slaves in the 1850 Census, and New Jersey only one and New Hampshire none in the 1860 Census, slavery was never prohibited in either state until ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865[102] (and New Jersey was one of the last states to ratify it).

None of the Southern states abolished slavery before 1865, but it was not unusual for individual slaveholders in the South to free numerous slaves, often citing revolutionary ideals, in their wills. Methodist, Quaker, and Baptist preachers traveled in the South, appealing to slaveholders to manumit their slaves, and there were "manumission societies" in some Southern states. By 1810, the number and proportion of free blacks in the population of the United States had risen dramatically. Most free blacks lived in the North, but even in the Upper South, the proportion of free blacks went from less than one percent of all blacks to more than ten percent, even as the total number of slaves was increasing through imports.[103]

One of the early Puritan writings on this subject was "The Selling of Joseph," by Samuel Sewall in 1700. In it, Sewall condemned slavery and the slave trade and refuted many of the era's typical justifications for slavery.[104][105] The Puritan influence on slavery was still strong at the time of the American Revolution and up until the Civil War. Of America's first seven presidents, the two who did not own slaves, John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams, came from Puritan New England. They were wealthy enough to own slaves, but they chose not to because they believed that it was morally wrong to do so. In 1765, colonial leader Samuel Adams and his wife were given a slave girl as a gift. They immediately freed her. Just after the Revolution, in 1787, the Northwest Territory (which became the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota) was opened up for settlement. The two men responsible for establishing this territory were Manasseh Cutler and Rufus Putnam. They came from Puritan New England, and they insisted that this new territory, which doubled the size of the United States, was going to be "free soil" – no slavery. This was to prove crucial in the coming decades. If those states had become slave states, and their electoral votes had gone to Abraham Lincoln's main opponent, Lincoln would not have been elected president.[54][55][56]

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the abolitionists, such as Theodore Parker, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Frederick Douglass, repeatedly used the Puritan heritage of the country to bolster their cause. The most radical anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, invoked the Puritans and Puritan values over a thousand times. Parker, in urging New England Congressmen to support the abolition of slavery, wrote that "The son of the Puritan ... is sent to Congress to stand up for Truth and Right ..."[107][108]

Northerners predominated in the westward movement into the Midwestern territory after the American Revolution; as the states were organized, they voted to prohibit slavery in their constitutions when they achieved statehood: Ohio in 1803, Indiana in 1816 and Illinois in 1818. What developed was a Northern block of free states united into one contiguous geographic area that generally shared an anti-slavery culture. The exceptions were the areas along the Ohio River settled by Southerners: the southern portions of Indiana, Ohio and Illinois. Residents of those areas generally shared in Southern culture and attitudes. In addition, these areas were devoted to agriculture longer than the industrializing northern parts of these states, and some farmers used slave labor. In Illinois, for example, while the trade in slaves was prohibited, it was legal to bring slaves from Kentucky into Illinois and use them there, as long as the slaves left Illinois one day per year (they were "visiting"). The emancipation of slaves in the North led to the growth in the population of Northern free blacks, from several hundred in the 1770s to nearly 50,000 by 1810.[109]

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, abolitionism, a movement to end slavery, grew in strength; most abolitionist societies and supporters were in the North. They worked to raise awareness about the evils of slavery, and to build support for abolition. After 1830, abolitionist and newspaper publisher William Lloyd Garrison promoted emancipation, characterizing slaveholding as a personal sin. He demanded that slaveowners repent and start the process of emancipation. His position increased defensiveness on the part of some Southerners, who noted the long history of slavery among many cultures. A few abolitionists, such as John Brown, favored the use of armed force to foment uprisings among the slaves, as he attempted to do at Harper's Ferry. Most abolitionists tried to raise public support to change laws and to challenge slave laws. Abolitionists were active on the lecture circuit in the North, and often featured escaped slaves in their presentations. Writer and orator Frederick Douglass became an important abolitionist leader after escaping from slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) was an international bestseller, and along with the non-fiction companion A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, aroused popular sentiment against slavery.[110] It also provoked the publication of numerous anti-Tom novels by Southerners in the years before the American Civil War.

This struggle took place amid strong support for slavery among white Southerners, who profited greatly from the system of enslaved labor. But slavery was entwined with the national economy; for instance, the banking, shipping, insurance, and manufacturing industries of New York City all had strong economic interests in slavery, as did similar industries in other major port cities in the North. The Northern textile mills in New York and New England processed Southern cotton and manufactured clothes to outfit slaves. By 1822, half of New York City's exports were related to cotton.[111]

Slaveholders began to refer to slavery as the "peculiar institution" to differentiate it from other examples of forced labor. They justified it as less cruel than the free labor of the North.

The principal organized bodies to advocate abolition and anti-slavery reforms in the north were the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and the New York Manumission Society. Before the 1830s the antislavery groups called for gradual emancipation.[112] By the late 1820s, under the impulse of religious evangelicals such as Beriah Green, the sense emerged that owning slaves was a sin and the owner had to immediately free himself from this grave sin by immediate emancipation.[113]

Prohibiting the international trade

Under the Constitution, Congress could not prohibit the import slave trade that was allowed in South Carolina until 1808. However, the third Congress regulated against it in the Slave Trade Act of 1794, which prohibited American shipbuilding and outfitting for the trade. Subsequent acts in 1800 and 1803 sought to discourage the trade by banning American investment in the trade, and American employment on ships in the trade, as well as prohibiting importation into states that had abolished slavery, which all states except South Carolina had by 1807.[114][115] The final Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves was adopted in 1807 and went into effect in 1808. However, illegal importation of African slaves (smuggling) was common.[4] The Cuban slave trade between 1796 and 1807 was dominated by American slave ships. Despite the 1794 Act, Rhode Island slave ship owners found ways to continue supplying the slave-owning states. The overall U.S. slave-ship fleet in 1806 was estimated to be almost 75% the size of that of the British.[116]: 63, 65

After Great Britain and the United States outlawed the international slave trade in 1807, British slave trade suppression activities began in 1808 through diplomatic efforts and the formation of the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron in 1809. The United States denied the Royal Navy the right to stop and search U.S. ships suspected as slave ships, so not only were American ships unhindered by British patrols, but slavers from other countries would fly the American flag to try to avoid being stopped. Co-operation between the United States and Britain was not possible during the War of 1812 or the period of poor relations in the following years. In 1820, the United States Navy sent USS Cyane under the command of Captain Edward Trenchard to patrol the slave coasts of West Africa. Cyane seized four American slave ships in her first year on station. Trenchard developed a good level of co-operation with the Royal Navy. Four additional U.S. warships were sent to the African coast in 1820 and 1821. A total of 11 American slave ships were taken by the U.S. Navy over this period. Then American enforcement activity reduced. There was still no agreement between the United States and Britain on a mutual right to board suspected slave traders sailing under each other's flag. Attempts to reach such an agreement stalled in 1821 and 1824 in the United States Senate. A U.S. Navy presence, however sporadic, did result in American slavers sailing under the Spanish flag, but still as an extensive trade. The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 set a guaranteed minimum level of patrol activity by the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy, and formalized the level of co-operation that had existed in 1820. Its effects, however, were minimal[lower-alpha 2] while opportunities for greater co-operation were not taken. The U.S. transatlantic slave trade was not effectively suppressed until 1861, during Lincoln's presidency, when a treaty with Britain was signed whose provisions included allowing the Royal Navy to board, search and arrest slavers operating under the American flag.[116]: 399–400, 449, 1144, 1149 [117]

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, British Royal Navy commanders of the blockading fleet were instructed to offer freedom to defecting American slaves, as the Crown had during the Revolutionary War. Thousands of escaped slaves went over to the Crown with their families.[118] Men were recruited into the Corps of Colonial Marines on occupied Tangier Island, in the Chesapeake Bay. Many freed American slaves were recruited directly into existing West Indian regiments, or newly created British Army units. The British later resettled a few thousand freed slaves to Nova Scotia. Their descendants, together with descendants of the black people resettled there after the Revolution, have established the Black Loyalist Heritage Museum.[119]

Slaveholders, primarily in the South, had considerable "loss of property" as thousands of slaves escaped to the British lines or ships for freedom, despite the difficulties.[119] The planters' complacency about slave "contentment" was shocked by seeing that slaves would risk so much to be free.[119] Afterward, when some freed slaves had been settled at Bermuda, slaveholders such as Major Pierce Butler of South Carolina tried to persuade them to return to the United States, to no avail.

The Americans protested that Britain's failure to return all slaves violated the Treaty of Ghent. After arbitration by the Tsar of Russia, the British paid $1,204,960 in damages (about $31.2 million in today's money) to Washington, which reimbursed the slaveowners.[120]

Slave rebellions

According to Herbert Aptheker, "there were few phases of ante-bellum Southern life and history that were not in some way influenced by the fear of, or the actual outbreak of, militant concerted slave action."[121]

Historians in the 20th century identified 250 to 311 slave uprisings in U.S. and colonial history.[122] Those after 1776 include:

- Gabriel's conspiracy (1800)

- Igbo Landing slave escape and mass suicide (1803)

- Chatham Manor Rebellion (1805)

- 1811 German Coast uprising, (1811)[123]

- George Boxley Rebellion (1815)

- Denmark Vesey's conspiracy (1822)

- Nat Turner's slave rebellion (1831)

- Black Seminole Slave Rebellion (1835–1838)[124]

- Amistad seizure (1839)[125]

- 1842 Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation[126]

In 1831, Nat Turner, a literate slave who claimed to have spiritual visions, organized a slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia; it was sometimes called the Southampton Insurrection. Turner and his followers killed nearly sixty white inhabitants, mostly women and children. Many of the men in the area were attending a religious event in North Carolina.[127] Eventually Turner was captured with 17 other rebels, who were subdued by the militia.[127] Turner and his followers were hanged, and Turner's body was flayed. In a frenzy of fear and retaliation, the militia killed more than 100 slaves who had not been involved in the rebellion. Planters whipped hundreds of innocent slaves to ensure resistance was quelled.[127]

This rebellion prompted Virginia and other slave states to pass more restrictions on slaves and free people of color, controlling their movement and requiring more white supervision of gatherings. In 1835, North Carolina withdrew the franchise for free people of color, and they lost their vote.

There are four known mutinies on vessels involved in the coastwise slave trade: Decatur (1826), Governor Strong (1826), Lafayette (1829), and the Creole (1841).[128]

Post-revolution Southern manumissions

Although Virginia, Maryland and Delaware were slave states, the latter two already had a high proportion of free blacks by the outbreak of war. Following the Revolution, the three legislatures made manumission easier, allowing it by deed or will. Quaker and Methodist ministers in particular urged slaveholders to free their slaves. The number and proportion of freed slaves in these states rose dramatically until 1810. More than half of the number of free blacks in the United States were concentrated in the Upper South. The proportion of free blacks among the black population in the Upper South rose from less than 1 percent in 1792 to more than 10 percent by 1810.[103] In Delaware, nearly 75 percent of black people were free by 1810.[129]

In the United States as a whole, the number of free blacks reached 186,446, or 13.5 percent of all black people by 1810.[130] After that period, few slaves were freed, as the development of cotton plantations featuring short-staple cotton in the Deep South drove up the internal demand for slaves in the domestic slave trade and high prices being paid for them.[131]

South Carolina made manumission more difficult, requiring legislative approval of every manumission. Alabama banned free black people from the state beginning in 1834; free people of color who crossed the state line were subject to enslavement.[132] Free black people in Arkansas after 1843 had to buy a $500 good-behavior bond, and no unenslaved black person was legally allowed to move into the state.[133]

Female slave owners

Women exercised their right to own and control human property without their husbands' interference or permission, and they were active participants in the slave trade.[134] For example, in South Carolina 40% of bills of sale for slaves from the 1700s to the present included a female buyer or seller.[135] Women also governed their slaves in a manner similar to men, engaging in the same levels of physical disciplining. Like men, they brought lawsuits against those who jeopardized their ownership to their slaves.[136]

Black slave owners

Despite the longstanding color line in the United States, some African Americans were slave owners themselves, some in cities and others as plantation owners in the country.[137] Slave ownership signified both wealth and increased social status.[137] Black slave owners were uncommon, however, as "of the two and a half million African Americans living in the United States in 1850, the vast majority [were] enslaved."[137]

Native American slave owners

After 1800, some of the Cherokee and the other four civilized tribes of the Southeast started buying and using black slaves as labor. They continued this practice after removal to Indian Territory in the 1830s, when as many as 15,000 enslaved blacks were taken with them.[138]

The nature of slavery in Cherokee society often mirrored that of white slave-owning society. The law barred intermarriage of Cherokees and enslaved African Americans, but Cherokee men had unions with enslaved women, resulting in mixed-race children.[139][140] Cherokee who aided slaves were punished with one hundred lashes on the back. In Cherokee society, persons of African descent were barred from holding office even if they were also racially and culturally Cherokee. They were also barred from bearing arms and owning property. The Cherokee prohibited the teaching of African Americans to read and write.[141][142]

By contrast, the Seminole welcomed into their nation African Americans who had escaped slavery (Black Seminoles). Historically, the Black Seminoles lived mostly in distinct bands near the Native American Seminole. Some were held as slaves of particular Seminole leaders. Seminole practice in Florida had acknowledged slavery, though not the chattel slavery model common elsewhere. It was, in fact, more like feudal dependency and taxation.[143][144][145] The relationship between Seminole blacks and natives changed following their relocation in the 1830s to territory controlled by the Creek who had a system of chattel slavery. Pro slavery pressure from Creek and pro-Creek Seminole and slave raiding led to many Black Seminoles escaping to Mexico.[146][147][148][149][150]

High demand and smuggling

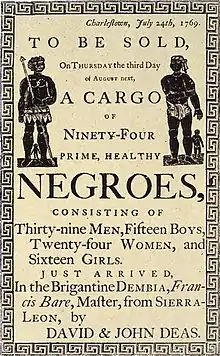

The United States Constitution, adopted in 1787, prevented Congress from completely banning the importation of slaves until 1808, although Congress regulated against the trade in the Slave Trade Act of 1794, and in subsequent Acts in 1800 and 1803.[114][151] During and after the Revolution, the states individually passed laws against importing slaves. By contrast, the states of Georgia and South Carolina reopened their trade due to demand by their upland planters, who were developing new cotton plantations: Georgia from 1800 until December 31, 1807, and South Carolina from 1804. In that period, Charleston traders imported about 75,000 slaves, more than were brought to South Carolina in the 75 years before the Revolution.[152] Approximately 30,000 were imported to Georgia.

By January 1, 1808, when Congress banned further imports, South Carolina was the only state that still allowed importation of enslaved people. The domestic trade became extremely profitable as demand rose with the expansion of cultivation in the Deep South for cotton and sugar cane crops. Slavery in the United States became, more or less, self-sustaining by natural increase among the current slaves and their descendants. Maryland and Virginia viewed themselves as slave producers, seeing "producing slaves" as resembling animal husbandry. Workers, including many children, were relocated by force from the upper to the lower South.

Despite the ban, slave imports continued through smugglers bringing in slaves past the U.S. Navy's African Slave Trade Patrol to South Carolina, and overland from Texas and Florida, both under Spanish control.[153] Congress increased the punishment associated with importing slaves, classifying it in 1820 as an act of piracy, with smugglers subject to harsh penalties, including death if caught. After that, "it is unlikely that more than 10,000 [slaves] were successfully landed in the United States."[154] But, some smuggling of slaves into the United States continued until just before the start of the Civil War.

Colonization movement

In the early part of the 19th century, other organizations were founded to take action on the future of black Americans. Some advocated removing free black people from the United States to places where they would enjoy greater freedom; some endorsed colonization in Africa, while others advocated emigration, usually to Haiti. During the 1820s and 1830s, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was the primary organization to implement the "return" of black Americans to Africa.[155] The ACS was made up mostly of Quakers and slaveholders, and they found uneasy common ground in support of what was incorrectly called "repatriation". By this time, however, most black Americans were native-born and did not want to emigrate, saying they were no more African than white Americans were British. Rather, they wanted full rights in the United States, where their families had lived and worked for generations.

In 1822, the ACS and affiliated state societies established what would become the colony of Liberia, in West Africa.[156] The ACS assisted thousands of freedmen and free blacks (with legislated limits) to emigrate there from the United States. Many white people considered this preferable to emancipation in the United States. Henry Clay, one of the founders and a prominent slaveholder politician from Kentucky, said that blacks faced:

...unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off.[157]

Deportation would also be a way to prevent reprisals against former slaveholders and white people in general, as had occurred in the 1804 Haiti massacre, which had contributed to a consuming fear amongst whites of retributive black violence, a phobia dubbed Haitianism.

Domestic slave trade and forced migration

The U.S. Constitution barred the federal government from prohibiting the importation of slaves for twenty years. Various states passed bans on the international slave trade during that period; by 1808, the only state still allowing the importation of African slaves was South Carolina. After 1808, legal importation of slaves ceased, although there was smuggling via Spanish Florida and the disputed Gulf Coast to the west.[158]: 48–49 [159]: 138 This route all but ended after Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821 (but see slave ships Wanderer and Clotilda).

The replacement for the importation of slaves from abroad was increased domestic production. Virginia and Maryland had little new agricultural development, and their need for slaves was mostly for replacements for decedents. Normal reproduction more than supplied these: Virginia and Maryland had surpluses of slaves. Their tobacco farms were "worn out"[160] and the climate was not suitable for cotton or sugar cane. The surplus was even greater because slaves were encouraged to reproduce (though they could not marry). The pro-slavery Virginian Thomas Roderick Dew wrote in 1832 that Virginia was a "negro-raising state"; i.e. Virginia "produced" slaves.[161] According to him, in 1832 Virginia exported "upwards of 6,000 slaves" per year, "a source of wealth to Virginia".[162]: 198 A newspaper from 1836 gives the figure as 40,000, earning for Virginia an estimated $24,000,000 per year.[163][162]: 201 Demand for slaves was the strongest in what was then the southwest of the country: Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, and, later, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri. Here there was abundant land suitable for plantation agriculture, which young men with some capital established. This was expansion of the white, monied population: younger men seeking their fortune.

The most valuable crop that could be grown on a plantation in that climate was cotton. That crop was labor-intensive, and the least-costly laborers were slaves. Demand for slaves exceeded the supply in the southwest; therefore slaves, never cheap if they were productive, went for a higher price. As portrayed in Uncle Tom's Cabin (the "original" cabin was in Maryland),[164] "selling South" was greatly feared. A recently (2018) publicized example of the practice of "selling South" is the 1838 sale by Jesuits of 272 slaves from Maryland, to plantations in Louisiana, to benefit Georgetown University, which has been described as "ow[ing] its existence" to this transaction.[165][166][167]

The growing international demand for cotton led many plantation owners further west in search of suitable land. In addition, the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 enabled profitable processing of short-staple cotton, which could readily be grown in the uplands. The invention revolutionized the cotton industry by increasing fifty-fold the quantity of cotton that could be processed in a day. At the end of the War of 1812, fewer than 300,000 bales of cotton were produced nationally. By 1820, the amount of cotton produced had increased to 600,000 bales, and by 1850 it had reached 4,000,000. There was an explosive growth of cotton cultivation throughout the Deep South and greatly increased demand for slave labor to support it.[168] As a result, manumissions decreased dramatically in the South.[169]

Most of the slaves sold from the Upper South were from Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas, where changes in agriculture decreased the need for their labor and the demand for slaves. Before 1810, primary destinations for the slaves who were sold were Kentucky and Tennessee, but, after 1810, the Deep South states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas received the most slaves. This is where cotton became "king".[170] Meanwhile, the Upper South states of Kentucky and Tennessee joined the slave-exporting states.

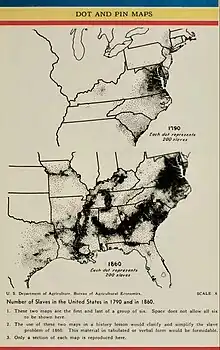

By 1815, the domestic slave trade had become a major economic activity in the United States; it lasted until the 1860s.[171] Between 1830 and 1840, nearly 250,000 slaves were taken across state lines.[171] In the 1850s, more than 193,000 enslaved persons were transported, and historians estimate nearly one million in total took part in the forced migration of this new "Middle Passage." By 1860, the slave population in the United States had reached four million.[171] Of the 1,515,605 free families in the fifteen slave states in 1860, nearly 400,000 held slaves (roughly one in four, or 25%),[172] amounting to 8% of all American families.[173]

.jpg.webp)

The historian Ira Berlin called this forced migration of slaves the "Second Middle Passage" because it reproduced many of the same horrors as the Middle Passage (the name given to the transportation of slaves from Africa to North America). These sales of slaves broke up many families and caused much hardship. Characterizing it as the "central event" in the life of a slave between the American Revolution and the Civil War, Berlin wrote that, whether slaves were directly uprooted or lived in fear that they or their families would be involuntarily moved, "the massive deportation traumatized black people, both slave and free".[174] Individuals lost their connection to families and clans. Added to the earlier colonists combining slaves from different tribes, many ethnic Africans lost their knowledge of varying tribal origins in Africa. Most were descended from families that had been in the United States for many generations.[171]

The firm of Franklin and Armfield was a leader in this trade. In the 1840s, almost 300,000 slaves were transported, with Alabama and Mississippi receiving 100,000 each. During each decade between 1810 and 1860, at least 100,000 slaves were moved from their state of origin. In the final decade before the Civil War, 250,000 were transported. Michael Tadman wrote in Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (1989) that 60–70% of inter-regional migrations were the result of the sale of slaves. In 1820, a slave child in the Upper South had a 30 percent chance of being sold South by 1860.[175] The death rate for the slaves on their way to their new destination across the American South was less than that suffered by captives shipped across the Atlantic Ocean, but mortality nevertheless was higher than the normal death rate.

Slave traders transported two-thirds of the slaves who moved West.[176] Only a minority moved with their families and existing master. Slave traders had little interest in purchasing or transporting intact slave families; in the early years, planters demanded only the young male slaves needed for heavy labor. Later, in the interest of creating a "self-reproducing labor force", planters purchased nearly equal numbers of men and women. Berlin wrote:

The internal slave trade became the largest enterprise in the South outside the plantation itself, and probably the most advanced in its employment of modern transportation, finance, and publicity. The slave trade industry developed its own unique language, with terms such as "prime hands, bucks, breeding wenches, and "fancy girls" coming into common use.[177]

The expansion of the interstate slave trade contributed to the "economic revival of once depressed seaboard states" as demand accelerated the value of slaves who were subject to sale.[178] Some traders moved their "chattels" by sea, with Norfolk to New Orleans being the most common route, but most slaves were forced to walk overland. Others were shipped downriver from such markets as Louisville on the Ohio River, and Natchez on the Mississippi. Traders created regular migration routes served by a network of slave pens, yards and warehouses needed as temporary housing for the slaves. In addition, other vendors provided clothes, food and supplies for slaves. As the trek advanced, some slaves were sold and new ones purchased. Berlin concluded, "In all, the slave trade, with its hubs and regional centers, its spurs and circuits, reached into every cranny of southern society. Few southerners, black or white, were untouched."[179]

Once the trip ended, slaves faced a life on the frontier significantly different from most labor in the Upper South. Clearing trees and starting crops on virgin fields was harsh and backbreaking work. A combination of inadequate nutrition, bad water and exhaustion from both the journey and the work weakened the newly arrived slaves and produced casualties. New plantations were located at rivers' edges for ease of transportation and travel. Mosquitoes and other environmental challenges spread disease, which took the lives of many slaves. They had acquired only limited immunities to lowland diseases in their previous homes. The death rate was so high that, in the first few years of hewing a plantation out of the wilderness, some planters preferred whenever possible to use rented slaves rather than their own.[180]

The harsh conditions on the frontier increased slave resistance and led owners and overseers to rely on violence for control. Many of the slaves were new to cotton fields and unaccustomed to the "sunrise-to-sunset gang labor" required by their new life. Slaves were driven much harder than when they had been in growing tobacco or wheat back East. Slaves had less time and opportunity to improve the quality of their lives by raising their own livestock or tending vegetable gardens, for either their own consumption or trade, as they could in the East.[181]

In Louisiana, French colonists had established sugar cane plantations and exported sugar as the chief commodity crop. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Americans entered the state and joined the sugar cultivation. Between 1810 and 1830, planters bought slaves from the North and the number of slaves increased from fewer than 10,000 to more than 42,000. Planters preferred young males, who represented two-thirds of the slave purchases. Dealing with sugar cane was even more physically demanding than growing cotton. The largely young, unmarried male slave force made the reliance on violence by the owners "especially savage".[182]

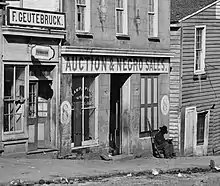

New Orleans became nationally important as a slave market and port, as slaves were shipped from there upriver by steamboat to plantations on the Mississippi River; it also sold slaves who had been shipped downriver from markets such as Louisville. By 1840, it had the largest slave market in North America. It became the wealthiest and the fourth-largest city in the nation, based chiefly on the slave trade and associated businesses.[68] The trading season was from September to May, after the harvest.[183]

The notion that slave traders were social outcasts of low reputation, even in the South, was initially promulgated by defensive southerners and later by figures like historian Ulrich B. Phillips.[184] Historian Frederic Bancroft, author of Slave-Trading in the Old South (1931) found—to the contrary of Phillips' position—that many traders were esteemed members of their communities.[185] Contemporary researcher Steven Deyle argues that the "trader's position in society was not unproblematic and owners who dealt with the trader felt the need to satisfy themselves that they acted honorably," while Michael Tadman contends that "'trader as outcast' operated at the level of propaganda" whereas white slave owners almost universally professed a belief that slaves were not human like them, and thus dismissed the consequences of slave trading as beneath consideration.[184] Similarly, historian Charles Dew read hundreds of letters to slave traders and found virtually zero narrative evidence for guilt, shame, or contrition about the slave trade: "If you begin with the absolute belief in white supremacy—unquestioned white superiority/unquestioned black inferiority—everything falls neatly into place: the African is inferior racial 'stock,' living in sin and ignorance and barbarism and heathenism on the 'Dark Continent' until enslaved...Slavery thus miraculously becomes a form of 'uplift' for this supposedly benighted and brutish race of people. And once notions of white supremacy and black inferiority are in place in the American South, they are passed on from one generation to the next with all the certainty and inevitability of a genetic trait."[186]

In the 1828 presidential election, candidate Andrew Jackson was strongly criticized by opponents as a slave trader who transacted in slaves in defiance of modern standards or morality.[187]

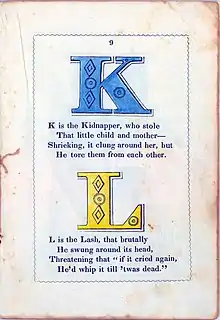

Treatment

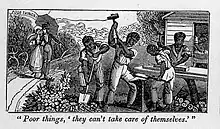

The treatment of slaves in the United States varied widely depending on conditions, time, and place, but in general it was brutal, especially on plantations. Whippings and rape were routine. The power relationships of slavery corrupted many whites who had authority over slaves, with children showing their own cruelty. Masters and overseers resorted to physical punishments to impose their wills. Slaves were punished by whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, mutilation, branding and imprisonment. Punishment was most often meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but sometimes abuse was carried out to re-assert the dominance of the master or overseer of the slave.[191] Treatment was usually harsher on large plantations, which were often managed by overseers and owned by absentee slaveholders, conditions permitting abuses.

William Wells Brown, who escaped to freedom, reported that on one plantation, slave men were required to pick eighty pounds per day of cotton, while women were required to pick seventy pounds; if any slave failed in his or her quota, they were subject to whip lashes for each pound they were short. The whipping post stood next to the cotton scales.[192] A New York man who attended a slave auction in the mid-19th century reported that at least three-quarters of the male slaves he saw at sale had scars on their backs from whipping.[193] By contrast, small slave-owning families had closer relationships between the owners and slaves; this sometimes resulted in a more humane environment but was not a given.[194]

Historian Lawrence M. Friedman wrote: "Ten Southern codes made it a crime to mistreat a slave. ... Under the Louisiana Civil Code of 1825 (art. 192), if a master was "convicted of cruel treatment", the judge could order the sale of the mistreated slave, presumably to a better master.[195] Masters and overseers were seldom prosecuted under these laws. No slave could give testimony in the courts.

According to Adalberto Aguirre's research, 1,161 slaves were executed in the United States between the 1790s and 1850s.[196] Quick executions of innocent slaves as well as suspects typically followed any attempted slave rebellions, as white militias overreacted with widespread killings that expressed their fears of rebellions, or suspected rebellions.

Although most slaves had lives that were very restricted in terms of their movements and agency, exceptions existed to virtually every generalization; for instance, there were also slaves who had considerable freedom in their daily lives: slaves allowed to rent out their labor and who might live independently of their master in cities, slaves who employed white workers, and slave doctors who treated upper-class white patients.[197] After 1820, in response to the inability to import new slaves from Africa and in part to abolitionist criticism, some slaveholders improved the living conditions of their slaves, to encourage them to be productive and to try to prevent escapes.[198] It was part of a paternalistic approach in the antebellum era that was encouraged by ministers trying to use Christianity to improve the treatment of slaves. Slaveholders published articles in Southern agricultural journals to share best practices in treatment and management of slaves; they intended to show that their system was better than the living conditions of northern industrial workers.

Medical care for slaves was limited in terms of the medical knowledge available to anyone. It was generally provided by other slaves or by slaveholders' family members, although sometimes "plantation physicians", like J. Marion Sims, were called by the owners to protect their investment by treating sick slaves. Many slaves possessed medical skills needed to tend to each other, and used folk remedies brought from Africa. They also developed new remedies based on American plants and herbs.[199]

An estimated nine percent of slaves were disabled due to a physical, sensory, psychological, neurological, or developmental condition. However, slaves were often described as disabled if they were unable to work or bear a child, and were often subjected to harsh treatment as a result.[200]

According to Andrew Fede, an owner could be held criminally liable for killing a slave only if the slave he killed was "completely submissive and under the master's absolute control".[201] For example, in 1791 the North Carolina General Assembly defined the willful killing of a slave as criminal murder, unless done in resisting or under moderate correction (that is, corporal punishment).[202]

While slaves' living conditions were poor by modern standards, Robert Fogel argued that all workers, free or slave, during the first half of the 19th century were subject to hardship.[203] Unlike free individuals, however, enslaved people were far more likely to be underfed, physically punished, sexually abused, or killed, with no recourse, legal or otherwise, against those who perpetrated these crimes against them.

In a very grim fashion, the commodification of the human body was legal in the case of African slaves as they were not legally seen as fully human. For the reason of slave punishment, decoration, or self-expression, the skin of slaves was in many instances allowed to be made into leather for furniture, accessories, and clothing.[204][205] Slave hair could be shaved and used for stuffing in pillows and furniture. In some instances, the inner body tissue of slaves (fat, bones, etc.) could be made into soap, trophies, and other commodities.[206]

Medical experimentation on slaves was also commonplace. Slaves were routinely used as medical specimens forced to take part in experimental surgeries, amputations, disease research, and developing medical techniques.[207] In many cases, slave cadavers were used in demonstrations and dissection tables.[208]

Sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, and forced breeding

Because of the power relationships at work, slave women in the United States were at high risk for rape and sexual abuse.[209][210] Their children were repeatedly taken away from them and sold as farm animals; usually they never saw each other again. Many slaves fought back against sexual attacks, and some died resisting. Others carried psychological and physical scars from the attacks.[211] Sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in a patriarchal Southern culture that treated black women as property or chattel.[210] Southern culture strongly policed against sexual relations between white women and black men on the purported grounds of racial purity but, by the late 18th century, the many mixed-race slaves and slave children showed that white men had often taken advantage of slave women.[210] Wealthy planter widowers, notably such as John Wayles and his son-in-law Thomas Jefferson, took slave women as concubines; each had six children with his partner: Elizabeth Hemings and her daughter Sally Hemings (the half-sister of Jefferson's late wife), respectively. Both Mary Chesnut and Fanny Kemble, wives of planters, wrote about this issue in the antebellum South in the decades before the Civil War. Sometimes planters used mixed-race slaves as house servants or favored artisans because they were their children or other relatives.[212] As a result of centuries of slavery and such relationships, DNA studies have shown that the vast majority of African Americans also have historic European ancestry, generally through paternal lines.[213][214]

Portrayals of black men as hypersexual and savage, along with ideals of protecting white women, were predominant during this time[215] and masked the experiences of sexual violence faced by black male slaves, especially by white women. Subject not only to rape and sexual exploitation, slaves faced sexual violence in many forms. A black man could be forced by his slaveowner to rape another slave or even a free black woman.[216] Forced pairings with other slaves, including forced breeding, which neither slave might desire, were common.[216] Through sexual and reproductive abuse slaveowners could further enforce their control over their slaves.

The prohibition on the importation of slaves into the United States after 1808 limited the supply of slaves in the United States. This came at a time when the invention of the cotton gin enabled the expansion of cultivation in the uplands of short-staple cotton, leading to clearing lands cultivating cotton through large areas of the Deep South, especially the Black Belt. The demand for labor in the area increased sharply and led to an expansion of the internal slave market. At the same time, the Upper South had an excess number of slaves because of a shift to mixed-crops agriculture, which was less labor-intensive than tobacco. To add to the supply of slaves, slaveholders looked at the fertility of slave women as part of their productivity, and intermittently forced the women to have large numbers of children. During this time period, the terms "breeders", "breeding slaves", "child bearing women", "breeding period", and "too old to breed" became familiar.[217]

As it became popular on many plantations to breed slaves for strength, fertility, or extra labor, there grew many documented instances of "breeding farms" in the United States. Slaves were forced to conceive and birth as many new slaves as possible. The largest farms were located in Virginia and Maryland.[218] Because the industry of slave breeding came from a desire for larger than natural population growth of slaves, slaveowners often turned towards systematic practices for creating more slaves. Female slaves "were subjected to repeated rape or forced sex and became pregnant again and again",[219] even by incest. In horrific accounts of former slaves, some stated that hoods or bags were placed over their heads to prevent them from knowing who they were forced to have sex with. Journalist William Spivey wrote, "It could be someone they know, perhaps a niece, aunt, sister, or their own mother. The breeders only wanted a child that could be sold."[220]

In the United States in the early 19th century, owners of female slaves could freely and legally use them as sexual objects. This follows free use of female slaves on slaving vessels by the crews.[221]: 83

The slaveholder has it in his power, to violate the chastity of his slaves. And not a few are beastly enough to exercise such power. Hence it happens that, in some families, it is difficult to distinguish the free children from the slaves. It is sometimes the case, that the largest part of the master's own children are born, not of his wife, but of the wives and daughters of his slaves, whom he has basely prostituted as well as enslaved.[222]: 38

"This vice, this bane of society, has already become so common, that it is scarcely esteemed a disgrace."[223]

"Fancy" was a code word which indicated that the girl or young woman was suitable for or trained for sexual use.[224]: 56 In some cases, children were also abused in this manner. The sale of a 13-year-old "nearly a fancy" is documented.[225] Zephaniah Kingsley, Jr., bought his wife when she was 13.[226]: 191