| Sonnet 12 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

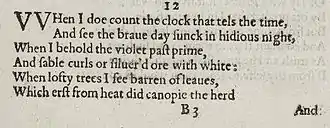

The first six lines of Sonnet 12 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 12 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

In the sonnet, the poet goes through a series of images of mortality, such as a clock, a withering flower, a barren tree and autumn, etc. Then, at the "turn" at the beginning of the third quatrain, the poet admits that the young man to whom the poem is addressed must go among the "wastes of time" just as all of the other images mentioned. The only way he can fight against Time, Shakespeare proposes, is by breeding and making a copy of himself.

Modern reading

- Clock: Hours on the clock, the time passing

- Brave: Having great beauty and/or splendor [2]

- Past prime: Declining from its perfection [3]

- Sable: Black (A Heraldic term) [3]

- Erst: Formerly, Once [3]

- Summer's Green: Foliage

- Sheaves: Bundles

- Bier: A frame used to carry a corpse to the grave.[3]

- Beard: In Elizabethan times, "beard" was pronounced as "bird" [3]

- Sweets: Virtues

- Others: Referencing other virtues and beauties

- 'gainst: Against

- Breed: Offspring, Descendants

- Brave: Defy .[3]

The sonnet is one long sentence, which helps to show the theme of time and its urgency.[4] It also suggests that it is one full and rounded thought, rather than many different points. There are also many contrasts showing time's power such as the words, "lofty" and "barren" when describing the trees, alluding to time's power over all of nature.[4] This sonnet also shows the power of time, in that it is deadly and not merciful. Shakespeare shows time's power by using the descriptive words of "white and bristly beard," "violet past prime," and "sable curls all silver'd o'er with white." One last image to take note of is the fact that the only way to defy time is by creating new virtues and beauties. And to do this, Shakespeare tells the young man, is by creating descendants.[4] This fact is shown in the volta, the last two lines of the sonnet, when Shakespeare says, "And nothing 'gainst time's scythe can make defence, / Save breed to brave him when he takes thee hence."

Structure

Sonnet 12 follows the structure of a typical Shakespearean sonnet.[5] It consists of 14 lines of which 12 belong to three quatrains and the last two belong to the couplet, with rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. Reflecting this structure, the first three quatrains develop an argument of despair, and the couplet suggests a (somewhat) hopeful resolution. However, the argument of the poem may also be seen as reflecting the older structure of the Petrarchan sonnet: lines one through eight are the octave[6] which concerns the decay that occurs in nature, and these lines are connected through alliteration.[7] Lines nine through fourteen form a rhetorical sestet [6] concerning the decay of the beloved.

The first line is often cited as (appropriately) displaying a metronomic regularity:

× / × / × / × / × / When I do count the clock that tells the time,

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Critical analysis

The sonnet's position in the sequence at number 12 coincides with the 12 hours on a clock-face.[8] Sonnet 12 also represents the first time in which the speaker's first person pronoun, "I" (also a mark on a clock's face), dominates the poem, indicating the beginning of his voice's ascendancy in the unfolding drama of the sequence.[9] Helen Vendler proposes the poem holds two models of time: one of gradual decay, and one of an aggressive emblem-figure of Time with his scythe. These ideas call up two approaches of Death: one sad and innocent in which everything slowly wastes away, growing barren and aged, and one in which the reaper actively cuts them down and takes them away as if life had been murdered.[9]

As Vendler notes, the first 12 lines of the poem are associated with the innocent death of decay with time. Carl Atkins adds to this, describing how much of the imagery used is transmuted from lively, growing identities to macabre indifference, such as "the harvest-home .. into a funeral, and the wagon laden with ripened corn becomes a bier bearing the aged dead".[2] These lines bring Time's aging decay into the spotlight as a natural and inexorable force in the world.

The crux of Vendler's analysis comes out of the phrase 'Sweets and Beauties' in line 11. She notes that the word "Beauties" is clearly a reference back to the earlier lines containing aesthetic beauties that wither away with time, and that "Sweets" has a deeper, moral context. She holds that Beauties are outward show and Sweets are inward virtues, and that both fade with the passage of time.[9] An example of one of the 'beauties' with a virtuous provision can be found on line 6 in the 'virtuous generosity of the canopy sheltering the herd'. In Vendler's interpretation, the act of the canopy providing the herd with shelter from the elements is given freely, without expectation or need of anything in return. Such an act is classified as generosity and so is virtuous by nature. Atkins agrees, also noting that the "Sweet" favor of the canopy will share the same fate as the beauties, fading with time as the leaves disappear.[2] Michael Schoenfeldt's scholarly synopsis of the sonnet focuses on Vendler's analysis of the anthropomorphizing of the autumnal mortality, in particular the use of stark, particular words (barren, bier, beard) to replace, with anthropomorphic emphasis, more common descriptors (shed, corn, gathered, wagon, awn).[10] He views these careful linguistic choices to be essential in understanding the grim theme underlying beauty's demise.

In the latter portion of her analysis, Vendler proposes a third, voluntary approach to death. All the natural images used in the poem point to including death as part of the cycle of life and imply that some things must embrace death willingly to allow for new growth to flourish. The speaker goes on to associate breeding and procreation with a new supply of budding virtue in the final lines of the poem. This surrender of beauty and the proliferation of virtue is implied as the way to triumph over Time and Death, and is the primary message from the speaker.[9]

Interpretations

- Martin Jarvis, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI)

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- 1 2 3 Atkins, Carl. Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press 2007. Print. p. 53-54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shakespeare, William, and Stephen Booth. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New Haven: Yale UP, 1977. Print.

- 1 2 3 Gibson, Rex, ed. Shakespeare: The Sonnets. Cambridge: Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1997. Print.

- ↑ Saccio, Peter (1998). "Shakespeare: The Word and the Action Part I." The Teaching Company. Chantilly, VA. Print. pp. 8.

- 1 2 Saccio, Peter (1998). "Shakespeare: The Word and the Action Part I." The Teaching Company. Chantilly, VA. Print. pp 10.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 11". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Vendler, H. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Salem Press 1998 p96-100.

- ↑ Schoenfeldt, M. A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets, Blackwell Pub. 2007 pp 44-45.

References

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Saccio, Peter (1998). "Shakespeare: The Word and the Action Part I." The Teaching Company. Chantilly, VA.

- Wordsworth, W (1996). "The Sonnet." The Lotus Magazine. New York

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet_12_(Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet_12_(Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase of sonnet in modern language

- Analysis of the sonnet

.png.webp)