| Sonnet 78 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

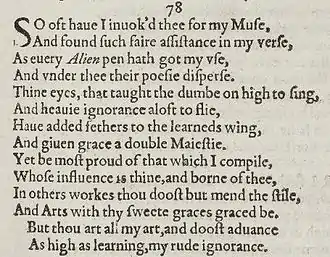

Sonnet 78 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 78 is one of 154 sonnets published by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare in 1609. It is one of the Fair Youth sequence, and the first of the mini-sequence known as the Rival Poet sonnets, thought to be composed some time from 1598 to 1600.

Exegesis

Invoking the youth as his muse, the speaker finds, has helped his poetry by providing direct inspiration, and this perhaps also refers to the help provided through patronage. The speaker notes that other poets have appropriated his way of invoking the young man, and this has helped them distribute their poetry, perhaps by being published, or by otherwise finding readers. The poet's strategy in this sonnet is to portray himself as ignorant and lacking in talent, but the second quatrain in lines 5 and 6 introduces sarcastic mock humility, by the ridiculousness of the image of croaking ("taught the dumb on high to sing"), paired with the image of heavy objects flying about ("heavy ignorance aloft to fly"). This is followed by the hyperbole of young men adding double majesty to grace. The poet encourages the youth to appreciate his work more, because the youth has wholly inspired the poet's works, and this primacy of his invocation has elevated him to the level of the most learned.[1][2]

Structure

Sonnet 78 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the rhyme scheme, abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a metre based on five feet in each line, and two syllables in each foot, accented weak/strong. Most of the lines are regular iambic pentameter, including the 5th line:

× / × / × / × / × / Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing (78.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Analysis

According to Helen Vendler, "Shakespeare excels in a form of verbal emphasis pointing up the conceptual oppositions of his verse." In this first poem of the Rival Poet sequence, "a firm antithesis is drawn between the putatively rude speaker and the other poets clustered round the young man." They are all "learned" and practicing both art and style, while "the poor speaker's ignorance is twice insisted on, as is his muteness (he was dumb) before he saw the young man."[3]

The poem gives us directions as to how we should read it and which words we should emphasize: "The words of the couplet tie — art, high, learning [learnèd], ignorance — repeat in little the topics that are under dispute."[3]

Michael Schoenfeldt notes, "the more whimsical complimentary sonnets, such as 78… such sonnets may be fanciful, but they are not frivolous… Read from the right angle, so to speak, they can be very beautiful, or at least delightful; and in them, as elsewhere Shakespeare is inventing some game or other and playing it out to its conclusion in deft and surprising ways.[4]

The words "pen", "feather", and "style" — used in stanza 1, 2, and 3 respectively — seem to be related. The word "pen" derives from the Latin word penna meaning feather, and in the Renaissance referred to a quill pen, and also was occasionally used to indicate a "feather". The word "style" in line 11 means a writer's literary style, though it also could be used as a synonym for "pen"; it derives from the Latin stilus meaning a writing instrument.[5]

"Dumb", "ignorance", "learned's", and "grace" are nouns that occur in the second stanza. The words "dumb" and "ignorance" could indicate the poet. "Learned" and "grace" could indicate a particular rival.[5]

In line 7, the poet uses a "metaphor from falconry and refers to the practice of imping, engrafting extra feathers in the wing of a bird"[5] in order to improve the health and flight of the bird. There are Italian allusions in Sonnet 78. For example, the phrase "penna d'ingegno" in Petrarch's sonnet 307, which means “pen of genius”, is analogous to Shakespeare's phrase “learned's wing”. The reference to falconry is often noted, but not the reference to Petrarch's sonnet.[6]

In line 12's "graces" and "graced", Shakespeare uses a stylistic figure known as polyptoton – the use of words that share the same root. The figure here occurs as a demonstration of what is stated in line 8.[5]

In line 13's phrase "thou art all my art" Shakespeare uses a rhetorical device known as antanaclasis, in which a word is used twice in different senses. The effect of the antanaclasis works as a metaphor for the basic meaning of the clause: "the beloved's being and the speaker's art are one and the same thing".[5] Joel Fineman suggests an alternative interpretation: "Instead of 'thou art all my art', writing itself stands — not subtly, but explicitly —between the poet's first and second persons. Writing itself (the same writing written by "I" the poet and by the "thou" of the young man) gives the poet an ontological and poetic art of interference whose transference both is and is not what it is supposed to be"[7]

Context

Sonnet 78 we find out about a rival who's male and a poet and whose entry initiates an episode of jealousy that comes to a close in only Sonnet 86.[8] The rivalry between the poets may appear to be literary, but, according to the critic Joseph Pequigney, it is in reality a sexual rivalry. This is disturbing because the subject in the sonnet is one that the persona has found erotically profitable, in part because the other poet may be superior in learning and style. Shakespeare is not concerned with poetic triumph he is vying only for the prize of a fair friend. The combat between the two rivals is indirect and the speaker never addresses his literary adversary and only mentions his beloved. It is the body language of Sonnet 78 (the first in the series) 79, 80 and 84 that serves to convert the topic of letters into that of eroticism. Shakespeare is known for his usage of puns and double meaning on words. So it isn't surprising that he uses wordplay in the first quatrain on "pen" for the male appendage, or, as a Stein-cum-Joyce might say, "a pen is a penis a pen," is fully utilized. The poet remarks at 78.4, "every alien pen hath got my use," where "alien" = 'of a stranger' and "use," besides 'literary practice,' can = 'carnal enjoyment.'[8] These sexual allusions are made in passing; they are overtones, restricted to a line or two.

Debate in Sonnet 78

In Sonnet 78, Shakespeare has a mock debate between the young man and himself: "The mock-debate of the sonnet is: should the young man be prouder of Shakespeare's poem compiled out of rude ignorance, or of those of his more learned admirers?" This question is followed by a mock answer: "The mock answer is that the young man should be prouder of having taught a hitherto dumb admirer to sing, and of having advanced ignorance as high as learning, because these achievements on his part testify more impressively to his originally power than his (slighter) accomplishments with respect to his learned poets — he but mends their style and graces their arts." The debate that Shakespeare presents is "in a Petrarchan logical structure, with a clearly demarcated octave and sestet." Shakespeare exhibits his present art as at least equal to that of his rivals. He accomplishes this "by first resorting to a country-bumpkin, fairy-tale idiot-son role, presenting himself as a Cinderella, so to speak, raised from the cinders to the skies."[3]

According to Helen Vendler,

The most interesting grammatical move in the poem is the use in Q2 of aspectual description: not "thou hast" as we would expect — to parallel the later "thou dost" and "thou art" — but thine eyes...have. The eyes govern the only four-line syntactic span (the rest of the poem is written in two-line units). We are made to pause for a two-line relative clause between thine eyes and its verb, have; in between subject and predicate we find ... the poet twice arising, once to sing, once to fly:

- Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing,

- And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

- Have added...[3]

Vendler compares the speaker's praise of the young man (sonnet 78) to his praise of the mistress's eyes (sonnet 132): "The speaker's yearning aspectual praise of the young man's eyes is comparable to his praise of the mistress' eyes in 132 (Thine eyes i love) the difference between direct second-person pronominal address to the beloved and third-person aspectual description of one of the beloved's attributes is exploited here and in 132."[3]

Towards the end of the second quatrain, Vendler begins to question some of the metaphors and figurative language that Shakespeare has used: "Does the learned's wing need added feathers? Coming after the first soaring of the speak, the heavy added feathers and given grace seem phonetically leaden, while later the line arts with thy sweet graces graced by suggest that the learned verse has become surfeited with elaboration."[3] Another author, R.J.C. Wait, has a contrasting view of the learned wings. "The learneds wings represents another poet to whom Southampton has given inspiration."[9]

The last two lines of the sonnet, the couplet, begins "but thou art my art." According to Vendler, "the phonetically and grammatically tautological pun — 'Thou art all my art ' — which conflates the copula and its predicate noun, enacts that plain mutual render, only me for thee (125) aspired to by the Sonnets and enacts as well the poet's simplicity contrasted with the affectations of the learned."[3]

Rival Poet

"Shakespeare's sonnets 78-86 concern the Speaker's rivalry with other poets and especially with one 'better spirit' who is 'learned' and 'polished'".[10] In Sonnet 78 we find out about a rival who is male and a poet and whose entry initiates an episode of jealousy that comes to a close in only Sonnet 86[8] These sonnets are considered to be the Rival Poet sonnets. The rival poet sonnets include three primary figures; the fair youth, the rival poet, and the lady who is desired by both men.

It is not known for certain whether the rival poet of sonnets 78 to 86 is fictional or is based on an actual person. Some suggest he may be George Chapman, Christopher Marlowe, Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, Barnabe Barnes, Gervase Markham, or Richard Barnfield.[11][12]

Notes

- 1 2 Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 262 ISBN 9781408017975.

- ↑ Hammond, Gerald. The Reader and the Young Man Sonnets. Barnes & Noble. 1981. p. 98-99. ISBN 978-1-349-05443-5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vendler, Helen Hennessy. "78." The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: Belknap of Harvard UP, 1998. 351. Print.

- ↑ "Strategies of Unfolding." Compassion to Shakespeare Sonnets. Ed. Michael Schoenfeldt. Malden: Blackwell Pub, 2007. 38. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Booth, Stephen. "Sonnet 78." Shakespeare's Sonnets: Edited with Anaylitic Commentary. Westford: Murray, 1977. Print

- ↑ Eriksen, Roy T. "Extant And In Choice Italian: Possible Italian Echoes In Julius Caesar And Sonnet 78." English Studies 69.3 (1988): 224. Academic Search Complete. Web. 6 Feb. 2012.Eriksen, Roy T. "Extant And In Choice Italian: Possible Italian Echoes In Julius Caesar And Sonnet 78." English Studies 69.3 (1988): 224. Academic Search Complete. Web. 6 Feb. 2012.

- ↑ Fineman, Joel. Shakespeare's Perjured Eye: The Invention of Poetic Subjectivity in the Sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986

- 1 2 3 Pequigney, Joseph. "Jealous Thoughts." Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare Sonnets. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1985. 103+. Print.

- ↑ Wait, J. C. The Background to Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Schocken, 1972. 78-80. Print.

- ↑ Jackson, Mac.D P. "Francis Meres and the Cultural Contexts of Shakespeare's Rival Poet Sonnets." Review of English Studies 56.224 (APR 2005): 224-46. Print.

- ↑ Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964. pp. 52, 127, 141-2, 303, 463.

- ↑ Leo Daugherty, William Shakespeare, Richard Barnfield, and the Sixth Earl of Derby, Cambria Press, 2010

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)