| Sonnet 153 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

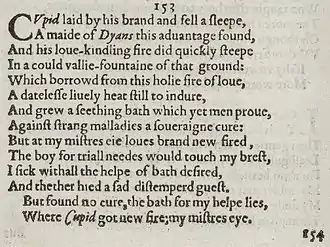

Sonnet 153 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 153 is a sonnet by William Shakespeare.

Synopsis

Sonnets 153 and 154 are filled with rather bawdy double entendres of sex followed by contraction of a venereal disease.[2] The sonnet is a story of Cupid, who lays down his torch and falls asleep, only to have it stolen by Diana, who extinguishes it in a "cold valley-fountain." The fountain then acquires an eternal heat as a result and becomes a hot spring where men still come to be cured of diseases. The speaker then states that as his mistress looks at him, Cupid's torch is ignited again, and Cupid tests the torch by trying it on the speaker's heart. The speaker becomes sick with love and wants to bathe in the hot spring to cure himself, but he cannot. The speaker discovers the only thing that can cure his discomfort is a glance from his mistress.

Structure

Sonnet 153 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form ABAB CDCD EFEF GG and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 12th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / And thither hied, a sad distemper'd guest, (153.12)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The 1st line begins with a common metrical variation, an initial reversal:

/ × × / × / × / × / Cupid laid by his brand and fell asleep: (153.1)

Line 9 potentially incorporates an initial reversal, and line 6 has a mid-line reversal. The 3rd line features the rightward movement of the first ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× × / / × / × / × / And his love-kindling fire did quickly steep (153.3)

A minor ionic also occurs in line 4.

The meter demands that line 10's "trial" be pronounced as two syllables.[3]

Analysis

Sonnets 153 and 154 are anacreontics,[4] a literary mode dealing with the topics of love, wine, and song, and often associated with youthful hedonism and a sense of carpe diem, in imitation of the Greek poet Anacreon and his epigones.[5] The two anacreontic sonnets are also most likely an homage to Edmund Spenser. Spenser's Amoretti and Epithalamion has a three-part structure: a sonnet sequence of 89 sonnets, a small series of anacreontic verses and a longer epithalamium. Shakespeare imitates Spenser with a sequence of 152 sonnets, two anacreontic sonnets and a long complaint.[6]

The central conceit of Sonnet 153 derives from a work by Marianus Scholasticus, a poet writing in Greek in the 5th-6th centuries AD. The original epigram reads in translation "Beneath these plane trees, detained by gentle slumber, Love slept, having put his torch in the care of the Nymphs; but the Nymphs said to one another 'Why wait? Would that together with this we could quench the fire in the hearts of men.' But the torch set fire even to the water, and with hot water thenceforth the Love-Nymphs fill the bath."[7]

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ (2004). Sparknotes:No Fear Shakespeare: The Sonnets. New York, NY: Spark Publishing. ISBN 1-4114-0219-7.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 535.

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Structure" Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. http://www.williamshakespeare-sonnets.com/structure

- ↑ Rosenmeyer, P. A. (2012). "Anacreontic". In Greene, Roland; Cushman, Stephen; et al. (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Fourth ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-691-13334-8.

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Structure" Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. http://www.williamshakespeare-sonnets.com/structure

- ↑ Paul Edmondson - Author, Stanely Wells, Shakespeare's Sonnets, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004, p.21

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)