| Stirtonia | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Atelidae |

| Subfamily: | Atelinae |

| Genus: | †Stirtonia Hershkovitz 1970 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

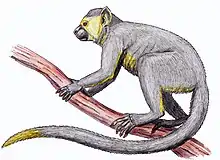

Stirtonia is an extinct genus of New World monkeys from the Middle Miocene (Laventan in the South American land mammal ages; 13.8 to 11.8 Ma). Its remains have been found at the Konzentrat-Lagerstätte of La Venta in the Honda Group of Colombia. Two species have been described, S. victoriae and the type species S. tatacoensis.[1][2] Synonyms are Homunculus tatacoensis, described by Ruben Arthur Stirton in 1951 and Kondous laventicus by Setoguchi in 1985.[3] The genus is classified in Alouattini as an ancestor to the modern howler monkeys.[4][5]

Etymology

Stirtonia is named after the scientist who first discovered it, Ruben Arthur Stirton. The two species, S. tatcoensis and S. victoriae, are named after the locations in which they were found: S. tatacoensis gets its name from the Tatacoa desert; and S. victoriae gets its name from the village “La Victoria” near its discovery site.[6][7][8]

Description

The genus is the largest primate found at La Venta,[9] with estimated body masses of S. tatacoensis at 5,513 grams (12.154 lb) and of S. victoriae at 10 kilograms (22 lb).[10] Stirtonia tatacoensis and S. victoriae are known by several teeth, a mandible and a maxilla that closely resemble, and are almost indistinguishable from, the living Alouatta.[11]

Fossil teeth found in the Solimões Formation at the Acre River in the border region of Brazil and Peru may belong to Stirtonia.[9][12]

Fossil record

A lower mandible fossil of S. tatacoensis was discovered during fieldwork between 1944 and 1949,[13] in the Honda Group, that has been dated to the Laventan, about 13 Ma.

Upper jaws and other cranial material of the large primate Stirtonia victoriae from the Perico Member of the La Dorada Formation, Honda Group were discovered in 1985 and 1986. Based on stratigraphic position, more than 300 metres (980 ft) below the Stirtonia tatacoensis type locality, this was the oldest primate material known until 1987 from Colombia.[14]

Evolution

The evolutionary split between Atelidae, of which Stirtonia, and Pitheciidae plus Callicebus, has been placed at 17.0 million years ago.[15]

Habitat

The Honda Group, and more precisely the "Monkey Beds", are the richest site for fossil primates in South America.[16] It has been argued that the monkeys of the Honda Group were living in habitat that was in contact with the Amazon and Orinoco Basins, and that La Venta itself was probably seasonally dry forest.[17] From the same level as where Stirtonia tatacoensis has been found, also fossils of Aotus dindensis, Micodon, Mohanamico, Saimiri annectens, Saimiri fieldsi and Cebupithecia have been uncovered.[18][19][20] Stirtonia reinforced the notion that leaf-eating was an enduring and essential aspect of the howler monkey's ecophylogenetic biology.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ Stirtonia victoriae at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Stirtonia tatacoensis at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Setoguchi et al., 1986a, p.2

- ↑ McKenna & Bell, 1997

- ↑ Takai et al., 2001, p.290

- ↑ Stirtonia Victoriae at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Stirtonia tatacoensis at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Kay et al., “Stirtonia victoriae, a new species of Miocene Colombian primate”, Journal of Human Evolution, February 1987

- 1 2 Defler, 2004, p.33

- ↑ Silvestro, 2017, p.14

- ↑ Pérez et al., 2013, p.4

- ↑ Tejedor, 2013, p.30

- ↑ Hershkovitz, 1970, p.1

- ↑ Kay et al., 1987, p.173

- ↑ Takai et al., 2001, p.304

- ↑ Rosenberger & Hartwig, 2001, p.3

- ↑ Lynch Alfaro et al., 2015, p.520

- ↑ Luchterhand et al., 1986, p.1753

- ↑ Wheeler, 2010, p.133

- ↑ Setoguchi et al., 1986b, p.762

- ↑ Rosenberger et al., 2015, p.24

Bibliography

- Defler, Thomas. 2004. Historia natural de los primates colombianos, 1–613. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Hershkovitz, Philip. 1970. Notes on Tertiary Platyrrhine monkeys and description of a new genus from the Late Miocene of Colombia. Folia Primatologica 12. 1–37. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Kay, Richard F.; Richard H. Madden; J. Michael Plavcan; Richard Cifelli, and Javier Guerrero Díaz. 1987. Stirtonia victoriae, a new species of Miocene Colombian primate. Journal of Human Evolution 16. 173–196. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Lynch Alfaro, Jessica W.; Liliana Cortés Ortiz; Anthony Di Fiore, and Jean P. Boubli. 2015. Special issue: Comparative biogeography of Neotropical primates. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82. 518–529. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- McKenna, Malcolm C., and Susan K. Bell. 1997. Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level, 1–631. Columbia University Press, New York, ISBN 0-231-11013-8.

- Rosenberger, Alfred L.; Siobhán B. Cooke; Lauren B. Halenar; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Walter C. Hartwig; Nelson M. Novo, and Yaneth Muñoz Saba. 2015. Howler Monkeys, Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects - Chapter 2 Fossil Alouattines and the Origins of Alouatta: Craniodental Diversity and Interrelationships, 21–54. Springer Science+Business Media New York.

- Rosenberger, Alfred L., and Walter Carl Hartwig. 2001. New World Monkeys. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences _. 1–4. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Setoguchi, Takeshi; Nobuo Shigehara, and Alberto Cadena G. 1986a. Kondous un nuevo primate ceboide de el Mioceno de La Venta, Colombia. Kyoto University overseas research reports of new world monkeys 5. 1–6. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Setoguchi, Takeshi; Nobuo Shigehara; Alfred L. Rosenberger, and Alberto Cadena G. 1986b. Primate fauna from the Miocene La Venta, in the Tatacoa Desert, Department of Huila, Colombia. Caldasia XV. 761–773. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Takai, Masanaru; Federico Anaya; Hisashi Suzuki; Nobuo Shigehara, and Takeshi Setoguchi. 2001. A New Platyrrhine from the Middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, and the Phyletic Position of Callicebinae. Anthropological Science, Tokyo 109.4. 289–307. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Tejedor, Marcelo F. 2013. Sistemática, evolución y paleobiogeografía de los primates Platyrrhini. Revista del Museo de La Plata 20. 20–39. Accessed 2017-09-24.

- Wheeler, Brandon. 2010. Community ecology of the Middle Miocene primates of La Venta, Colombia: the relationship between ecological diversity, divergence time, and phylogenetic richness. Primates 51.2. 131–138. Accessed 2017-09-24.

Further reading

- Fleagle, John G., and Alfred L. Rosenberger. 2013. The Platyrrhine Fossil Record, 1–256. Elsevier ISBN 9781483267074. Accessed 2017-10-21.

- Hartwig, W.C., and D.J. Meldrum. 2002. The Primate Fossil Record - Miocene platyrrhines of the northern Neotropics, 175–188. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08141-2. Accessed 2017-09-24.