Binzhou

滨州市 | |

|---|---|

| |

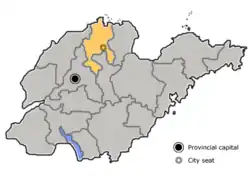

Location of Binzhou in Shandong | |

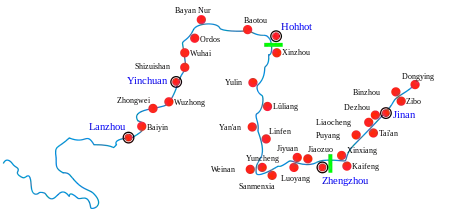

Binzhou Location in China | |

| Coordinates (Binzhou government): 37°22′59″N 117°58′16″E / 37.383°N 117.971°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Shandong |

| County-level divisions | 7 |

| Municipal seat | Bincheng District |

| Government | |

| • CPC Secretary | Zhang Guangfeng (张光峰) |

| • Mayor | Cui Honggang (崔洪刚) |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 9,453 km2 (3,650 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,041 km2 (402 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,041 km2 (402 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 20 m (70 ft) |

| Population (2020 census)[2] | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 3,928,568 |

| • Density | 420/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,188,597 |

| • Urban density | 1,100/km2 (3,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,188,597 |

| • Metro density | 1,100/km2 (3,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 256600 |

| Area code | 0543 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-SD-16 |

| License Plate Prefix | 鲁M |

| Binzhou | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 濱州 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 滨州 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Coastal Prefectural Capital | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Former names | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Putai, south of the Yellow River in 1878[3] | |||||||||

| Putai | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 蒲台 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 蒲台 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Pu Terrace | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Binzhou (Chinese: 滨州, bin-joe),[4] formerly Putai, is a prefecture-level city in northern Shandong Province in the People's Republic of China. The city proper sits on the northern bank of the Yellow River, while its administrative area straddles both sides of its lower course before its present delta. As of the 2020 census, its population was 3,928,568 inhabitants (3,748,474 in 2010), and its built-up (or metro) area made of Bincheng and Zhanhua urban Districts was home to 1,188,597 inhabitants.

History

Human settlement dates to at least the Chinese Neolithic. During the Shang, the area around Binzhou was held by the Pugu, who were counted among the "Eastern Barbarians" or Dongyi. Pugu joined the Shang prince Wu Geng's failed rebellion against the Zhou and was destroyed c. 1039, with its lands given to the minister Jiang Ziya as the march of Qi. The Bamboo Annals suggest the Pugu continued to trouble the Zhou for another decade and state they were again destroyed c. 1026. Qi became one of the most powerful of China's Warring States but was ruled from Yingqiu (modern Zibo), except for a brief hiatus under Duke Hu. He relocated to Bogu but was overcome by the revolting people of Yingqiu; his successor restored the former capital.

The name Binzhou arose under the Five Dynasties period because its land then bordered the Bay of Bohai. The deposition of silt from the Yellow River—which assumed its present course after the disastrous floods of the 1850s—has since moved the site well inland. The city itself was known as Putai into the 20th century,[5] but Putai County was abolished in March 1956 and the name now survives only as the town's Pucheng Subdistrict.

Public works have reduced the destructiveness of the river, permitting Binzhou and neighboring Dongying to be developed into cities. The former Huimin Prefecture (惠民地区) was renamed Binzhou in 1984. It was given city status in 1992. Its administrative area presently has more than 3.9 million inhabitants. The major Industries are based on oil, chemicals, and textiles.

Administration

The prefecture-level city of Binzhou administers seven county-level divisions, including two districts, one county-level city and four counties.

- Bincheng District (滨城区)

- Zhanhua District (沾化区)

- Zouping city (邹平市)

- Boxing County (博兴县)

- Huimin County (惠民县)

- Yangxin County (阳信县)

- Wudi County (无棣县)

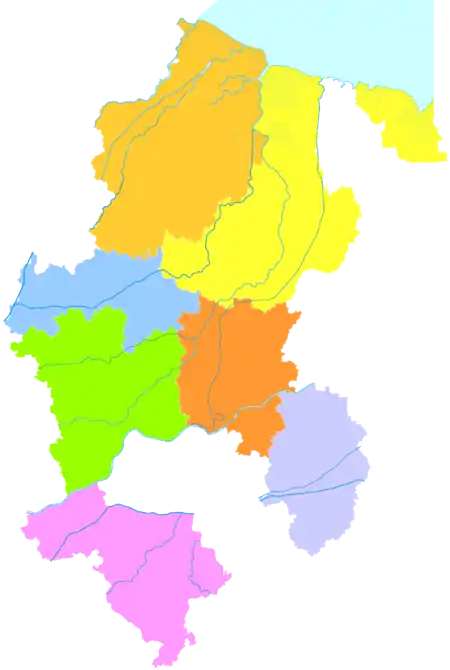

| Map |

|---|

Geography

Binzhou lies on the alluvial plain formed by the Yellow River. The entire length of countryside around the river from Pucheng Subdistrict to the Bay of Bohai has been created by deposition of sediment since the Qin Dynasty.[3] The present prefecture borders (counterclockwise from due west) Dezhou, Jinan, Zibo, Dongying, the Bay of Bohai, and Hebei.

Climate

Binzhou has a monsoon-influenced humid continental climate (Köppen Dwa), with four well-defined seasons. Binzhou is one of the warmest cities in the world with a continental climate, with summers reaching as high as 31 °C, and the average temperature in the city being 13.0 °C. Conditions are warm and nearly rainless in spring, hot and humid in summer, crisp in autumn and cold and dry in winter. More than half of the annual precipitation occurs in July and August alone; snow occasionally falls during winter, though heavy falls are very rare.

| Climate data for Binzhou (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1971–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.4 (65.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.3 (93.7) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.7 (105.3) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

36.8 (98.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

26.8 (80.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

2.0 (35.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

8.7 (47.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −21.1 (−6.0) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4.7 (0.19) |

9.8 (0.39) |

9.3 (0.37) |

27.2 (1.07) |

48.3 (1.90) |

79.1 (3.11) |

162.5 (6.40) |

153.2 (6.03) |

42.6 (1.68) |

27.7 (1.09) |

19.6 (0.77) |

5.2 (0.20) |

589.2 (23.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 7.6 | 10.9 | 9.6 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 63.8 |

| Average snowy days | 3.2 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 10 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61 | 58 | 53 | 55 | 60 | 64 | 77 | 80 | 73 | 69 | 67 | 63 | 65 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 162.6 | 165.2 | 214.9 | 236.4 | 267.1 | 235.1 | 195.7 | 198.4 | 200.7 | 194.8 | 162.8 | 154.9 | 2,388.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 54 | 58 | 60 | 61 | 53 | 44 | 48 | 54 | 57 | 54 | 52 | 54 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Administration[6][7] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather China[8] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Education

Notable people

- Sun Tzu, Spring and Autumn period military general and strategist, author of the Art of War.

- Xu Yan, kickboxer

- Zhang Shiping, businessman[9]

Economy

Binzhou, and neighboring Dongying, has historically had an agrarian economy. Binzhou is known regionally for its "dongzao" (literally, winter dates). After the Shengli Field was discovered, most of the field was incorporated into newly created Dongying, although Binzhou maintain some oil operations. Binzhou has been diversifying its economy away from agriculture by attracting manufacturing and foreign direct investment into the city. Among Binzhou's large businesses include Weiqiao, a textile company, and Binzhou Pride, a new auto company targeting the growing low-cost market. ±õÖÝÆÕÀ³µÂÆû³µ¹¤ÒµÓÐÏÞ¹«Ë¾

The Binzhou local government has also plowed resources into a new economic development zone on the outskirts of the new city, complete with a human-made lake. Binzhou economic development zone

Binzhou's role in pet food crisis

In April 2007, Binzhou made international headlines when Binzhou Futian Biology Technology, in Wudi County, was identified by US officials as one of two sources of contaminated wheat gluten in the 2007 pet food recalls. Shortly after, the company was shuttered by Chinese authorities, who also detained its general manager.[10]

Reform

In 2004, the Binzhou government implemented Democratic Political Discussion Day, held on the 5th of each month. Under this scheme, every village-level government on this day is required to hold "open debate" and conference for villagers (essentially a town hall). At these meetings, a monthly financial report is presented, highlighting past and planned expenditure, investment performance and such other financial information. In theory, this is supposed to open village finances to greater public scrutiny and debate. Also released at these meetings are reports on the past performance of the government and governmental officials, and future actions and decisions planned, and just like the financial reports, these are also under the public scrutiny and debate. The resulting event is a secret ballot for every villager to vote for everything discussed at these meetings and governments cannot proceed on any issues unless they are passed with a majority vote. The issues passed by popular vote would then be carried out, and at the same time, the government would also make improvement and adjustment on the policies and issues that did not pass, and then present the revisions for the public scrutiny and debate at the next meeting.

Result of the political reform

Ever since the implementation of the political reform at Binzhou, the policy and performance have become transparent and obvious, corruption was checked, cadres' performance and popular support increased, and economy has steadily developed. The letters of petition from villagers to the government reduced more than 30%, and more importantly, in comparison to the era prior to the implementation of the political reform where over 90% of the petitions were criticism and complaints, over 90% of the petition after the implementation of the political reform was suggestions for improvement and requests for assistance.

The obvious achievement of the political reform of Binzhou is widely reported in the domestic Chinese media, as well as many overseas Chinese media, such as Zhong Guo Daily News in Southern California, or its more commonly known Chinese name among local Chinese readers, China Daily (Not to be confused China Daily, the official English publication of Chinese government), and is termed by both domestic and overseas scholars as a good example for governments in other parts of China to follow, and along with Chinese media, they have urged authorities to slowly but steadily expand the reform to a greater scale.

City gallery

The center lake of Binzhou (2009)

The center lake of Binzhou (2009) It is one of summer evening public performs of Binzhou (2009)

It is one of summer evening public performs of Binzhou (2009) Old people practice Taiji in a residential area (2009)

Old people practice Taiji in a residential area (2009) A floral sculpture in park (2010)

A floral sculpture in park (2010) Evening (2010)

Evening (2010) A residential development in the new part of the city (2006)

A residential development in the new part of the city (2006) A random giant giraffe display in an old apartment complex (2006)

A random giant giraffe display in an old apartment complex (2006)

References

- ↑ 最新人口信息 www.hongheiku.com (in Chinese). hongheiku. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ↑ "China: Shāndōng (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de.

- 1 2 "China", Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. V, 1878***Please note that no wikilink is available to this article in EB9***

- ↑ "Twenty-five years of global education: 4-H Michigan China Art Project". MSU Extension. 26 June 2013.

- 1 2 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 166–231.

- ↑ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ↑ 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ↑ 滨州 - 气象数据 -中国天气网 (in Chinese). Weather China. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ↑ "Zhang Shiping". Forbes. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ David Barboza (June 5, 2007). "When Fakery Turns Fatal". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-06-22.