| Nikephoros II Phokas | |

|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

| |

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | 16 August 963 – 11 December 969 |

| Predecessor | Romanos II |

| Successor | John I |

| Born | c. 912 Cappadocia |

| Died | 11 December 969 (aged 57) Constantinople |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Theophano |

| Dynasty | Phokas |

| Father | Bardas Phokas |

Nikephoros II Phokas (Νικηφόρος Φωκᾶς; c. 912 – 11 December 969), Latinized Nicephorus II Phocas, was Byzantine emperor from 963 to 969. His career, not uniformly successful in matters of statecraft or of war, nonetheless greatly contributed to the resurgence of the Byzantine Empire during the 10th century. In the east, Nikephoros completed the conquest of Cilicia and retook the islands of Crete and Cyprus, opening the path for subsequent Byzantine incursions reaching as far as Upper Mesopotamia and the Levant; these campaigns earned him the sobriquet "pale death of the Saracens".

Early life and career

Nikephoros Phokas was born around 912. From his paternal side, he belonged to the Phokas family[2] which had produced several distinguished generals, including Nikephoros' father Bardas Phokas, brother Leo Phokas, and grandfather Nikephoros Phokas the Elder, who had all served as commanders of the field army (domestikos tōn scholōn). From his maternal side he belonged to the Maleinoi, a powerful Anatolian Greek family which had settled in Cappadocia.[3][4] Early in his life Nikephoros had married Stephano. She had died before he rose to fame, and after her death he took an oath of chastity.

Nikephoros II Phokas Emperor of the Romans | |

|---|---|

| Honored in | Orthodox Christianity |

| Feast | December 11 |

| Attributes | Imperial atire |

Early Eastern campaigns

Nikephoros joined the army at an early age. He was appointed the military governor of the Anatolic Theme in 945 under Emperor Constantine VII. In 954 or 955 Nikephoros was promoted to Domestic of the Schools, replacing his father, Bardas Phokas, who had suffered a series of defeats by the Hamdanids and by the Abbasids. The new position essentially placed Nikephoros in charge of the eastern Byzantine army. From 955, the Hamdanids in Aleppo entered a period of unbroken decline until their destruction in 1002. In June 957 Nikephoros managed to capture and destroy Adata. The Byzantines continued to push their advantage against the Arabs until the collapse of the Hamdanids, except for the period from 960 to 961, when the army turned its focus to the reconquest of Crete.

Conquest of Crete

From the ascension of Emperor Romanos II in 959, Nikephoros and his younger brother Leo Phokas were placed in charge of the eastern and western field armies respectively. In 960, 27,000 oarsmen and marines were assembled to man a fleet of 308 ships carrying 50,000 troops.[5][6] At the recommendation of the influential minister Joseph Bringas, Nikephoros was entrusted to lead this expedition against the Muslim Emirate of Crete, and he led his fleet to the island and defeated a minor Arab force upon disembarking near Almyros. He soon began a nine-month siege of the fortress town of Chandax, where his forces suffered through the winter due to supply issues.[7] Following a failed assault and many raids into the countryside, Nikephoros entered Chandax on 6 March 961 and soon wrested control of the entire island from the Muslims.[8] Upon returning to Constantinople, he was denied the usual honor of a triumph, but was permitted an ovation in the Hippodrome.[9]

Later Eastern campaigns

Following the conquest of Crete, Nikephoros returned to the east and marched a large and well-equipped army into Cilicia. In February 962 he captured Anazarbos, while the major city of Tarsus ceased to recognize the Hamdanid Emir of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla.[10] Nikephoros continued to ravage the Cilician countryside, defeating the governor of Tarsus, ibn al-Zayyat, in open battle; al-Zayyat later committed suicide on account of the loss. Thereafter, Nikephoros returned to the regional capital of Caesarea. Upon the beginning of the new campaigning season al-Dawla entered the Byzantine Empire to conduct raids, a strategy which left Aleppo dangerously undefended. Nikephoros soon took Syrian Hierapolis.[11] In December, an army split between Nikephoros and John I Tzimiskes marched towards Aleppo, quickly routing an opposing force led by Naja al-Kasaki. Al-Dawla's force caught up with the Byzantines, but he too was routed, and Nikephoros and Tzimiskes entered Aleppo on 24 December.[10] The loss of the city would prove to be both a strategic and moral disaster for the Hamdanids. It was probably on these campaigns that Nikephoros earned the sobriquet "The Pale Death of the Saracens".[12]

Ascension to the throne

On 15 March 963, Emperor Romanos II died unexpectedly at the age of twenty-six of uncertain cause. Both contemporary sources and later historians seem to either believe that the young Emperor had exhausted his health with the excesses of his sexual life and his heavy drinking, or suspect that the Empress Theophano (c. 941–after 976), his wife, poisoned him. Theophano had already gained a reputation as an intelligent and ambitious woman. Unfavorable accounts of her by later historians would characterize her as a woman known for ruthlessness in achieving her goals. Romanos had already crowned as co-emperors his two sons Basil II and Constantine VIII. At the time that Romanos died, however, Basil was five years old and Constantine only three years old, so Theophano was named regent.

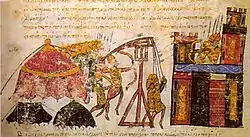

_into_Constantinople_in_963_from_the_Chronicle_of_John_Skylitzes.jpg.webp)

Theophano, however, was not allowed to rule alone. Joseph Bringas, the eunuch palace official who had become Romanos' chief councilor, maintained his position. According to contemporary sources he intended to keep authority in his own hands. He also tried to reduce the power of Nikephoros Phokas. The victorious general had been accepted as the actual commander of the army and maintained a strong connection to the aristocracy. Bringas was afraid that Nikephoros would attempt to claim the throne with the support of both the army and the aristocracy. This is exactly what he did. On July 2 in Caesarea, his armies, along with his highest-ranking officers, proclaimed Nikephoros emperor. From his position in Caesarea, and in advance of the news of his proclamation as emperor, Nikephoros sent a fleet to secure the Bosphorus Strait against his enemies.[13] Around the same time, he appointed Tzimiskes as Domestic of the East, now taking on the formal roles of emperor. He then sent a letter to Constantinople requesting to be accepted as co-emperor. In response, Bringas locked down the city, forcing Nikephoros' father Bardas Phokas to seek sanctuary in the Hagia Sophia, while his brother Leo Phokas escaped the city in disguise. Bringas was able to garner some support within the city from a few high-ranking officers, namely Marianos Argyros, but he himself was not a skilled orator and was unable to obtain the support of other popular officials such as the Patriarch Polyeuctus and the general Basil Lekapenos. The people of Constantinople soon turned against his cause, killing Argyros in a riot and soon forcing Bringas to flee.[14][15] On August 16, Nikephoros was proclaimed emperor and married the empress Theophano.[16]

Reign

Western Wars

Nikephoros II was not very successful in his western wars. Under his reign, relations with the Bulgarians worsened. It is likely that he bribed the Kievan Rus' to raid the Bulgarians in retaliation for them not blocking Magyar raids.[17] This breach in relations triggered a decades-long decline in Byzantine-Bulgarian diplomacy and was a prelude to the wars fought between the Bulgarians and later Byzantine emperors, particularly Basil II.

Nikephoros' first military failures came in Sicily. In 962 the son of the governor of Fatimid Sicily, Ahmad ibn al-Hasan al-Kalbi, captured and reduced the Byzantine city of Taormina. The last major Byzantine stronghold in Sicily, Rometta, appealed to the newly crowned emperor Nikephoros for aid against the approaching Muslim armies. Nikephoros renounced his payments of tribute to the Fatimid caliphs, and sent a huge fleet, purportedly boasting a crew of around 40,000 men, under Patrikios Niketas and Manuel Phokas, to the island. The Byzantine forces, however, were swiftly routed in Rometta and at the Battle of the Straits, and Rometta soon fell to the Muslims, completing the Islamic conquest of Sicily.[18][19]

In 967, the Byzantines and the Fatimids hastily concluded a peace treaty to cease hostilities in Sicily. Both empires had grander issues to attend to: the Fatimids were preparing to invade Egypt, and tensions were flaring up on mainland Italy between the Byzantines and the German emperor Otto I. The constant tension between the Germans and the Byzantines was largely due to mutual cultural biases, but also to the fact that both empires claimed to be the successors of the Roman Empire.[20] Conflicts in southern Italy were preceded by religious contests between the two empires and by the malicious writings of Liutprand of Cremona. Otto first invaded Byzantine Apulia in 968 and failed to take Bari. Early the next year, he once again moved against Byzantine Apulia and Calabria, but, unable to capture Cassano or Bovino, failed to make any progress. In May he returned north, leaving Pandulf Ironhead to take charge of the siege. Pandulf was defeated and taken prisoner by the Byzantine general Eugenios, who went on to besiege Capua and enter Salerno. The two empires would continue to skirmish with each other until after the reign of Nikephoros, but neither side was able to make permanent or significant gains.

Eastern Wars

From 964 to 965, Nikephoros led an army of 40,000 men which conquered Cilicia and conducted raids in Upper Mesopotamia and Syria, while the patrician Niketas Chalkoutzes recovered Cyprus.[21] In the spring of 964, Nikephorus headed east. During the summer he captured Anazarbos and Adana before withdrawing. Later that year, Nikephoros attempted to quickly take Mopsuestia, but failed, returning to Caesarea. It was around this time that Niketas Chalkoutzes instigated a coup in Cyprus, which at the time was a shared condominium between the Byzantines and the Arabs. In the summer of 965, the conquest of Cilicia began in earnest. Nikephorus and Tzimiskes seized Mopsuestia July 13, while Leo Phokas invested Tarsus and Nikephoros and Tzimiskes arrived soon after. Nikephoros won a pitched battle against the Tarsiots, routing their forces with his "ironclad horsemen", referencing the Byzantine cataphracts. Within a fortnight, on August 16, Tarsus surrendered. Nikephoros allowed the inhabitants to depart unharmed before the city was plundered by his army. With the fall of these two strongholds, Cilicia was in the hands of the Byzantines.[22][23]

In June 966, there was an exchange of prisoners between Sayf al-Dawla and the Byzantines, held at Samosata.[24] In October 966, Nikephoros led an expedition to raid Amida, Dara and Nisibis, then he marched towards Hierapolis, where he took a relic with the image of Jesus to be later placed in the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos in Constantinople.[24] He later sent a detachment to Barbalissos which returned with 300 prisoners, then he went to raid Wadi Butnan, Chalcis, Tizin and Artah, before laying siege to Antioch, but it was abandoned after eight days due to the lack of supplies.[25]

In 967 or 968, Nikephoros annexed the Armenian state of Taron by diplomacy,[26] in addition to Arzen and Martyropolis.[27] In October 968, Nikephoros conducted another expedition which started by besieging Antioch for thirteen days,[27] then he went south raiding and sacking most of the fortresses and cities along his path including Maarrat Misrin, Arra, Capharda, Larissa, Epiphania and Emesa in the Orontes valley until he reached the city of Tripoli, then he went to take Arca, Antarados, Maraclea, Gabala and received the submission of Laodicea.[28] His aim was to cut off Antioch from its allies: the city was unsuccessfully blockaded two times in 966 and 968, and so the emperor decided to take it by hunger (so as not to damage to city) and left a detachment (a taxiarchy) of 1500 men in the fort of Pagrae, which lies on the road from Antioch to Alexandretta. The commander of the fort, the patrikios Michael Bourtzes, disobeyed the emperor's orders and took Antioch with a surprise attack, supported by the troops of the stratopedarch Petros, eunuch of the Phokas family. Bourtzes was disgraced for his insubordination, and later joined the plot that killed Phokas.

Civil administration

.png.webp)

Nikephoros' popularity was largely based on his conquests. Due to the resources he allocated to his army, Nikephoros was compelled to exercise a rigid economic policy in other departments. He retrenched court largess and curtailed the immunities of the clergy, and while he had an ascetic disposition, he forbade the foundation of new monasteries. By his heavy imposts and the debasement of the Byzantine currency, along with the enforcement and implementation of taxes across the centralized regions of the empire, he forfeited his popularity with the people and gave rise to riots.

Nikephoros also disagreed with the church on theological grounds. He wished the church to elevate those soldiers who died in battle against the Saracens to the positions of martyrs in the church – similar to the status of "Shahid" which the Emperor's Muslim foes bestowed on their own fallen soldiers. In the Christian context, this was a highly controversial and unpopular demand.[29]

In 967, he sparked a controversy in the capital by making a display of his military maneuvers in the Hippodrome similar in style to those displayed by the emperor Justinian centuries earlier preceding the Nika riots and its violent suppression within the stadium itself. The crowd within the Hippodrome panicked and began a stampede to retreat from the stadium, resulting in numerous deaths.

Nikephoros was the author of extant treatises on military tactics, most famously the Praecepta Militaria, which contains valuable information on the art of war in his time, and the less-known On Skirmishing (Medieval Greek: Περὶ Παραδρομῆς Πολέμου), which concerned guerrilla-like tactics for defense against a superior enemy invasion force along the eastern frontier; though it purports that the tactics were no longer needed since the danger of the Muslim states to the east had subsided.[30] It is likely that this latter work, at least, was not composed by the Emperor but rather for him; translator and editor George T. Dennis suggests that it was perhaps written by his brother Leo Phokas, then Domestic of the West.[31] Nikephoros was a very devout man, and he helped his friend, the monk Athanasios, found the monastery of Great Lavra on Mount Athos.[32]

Assassination

The plot to assassinate Nikephoros began when he dismissed Michael Bourtzes from his position following his disobedience in the siege of Antioch. Bourtzes was disgraced, and he would soon find an ally with whom to plot against Nikephoros. Towards the end of 965, Nikephoros had John Tzimiskes exiled to eastern Asia Minor for suspected disloyalty, but was recalled on the pleading of Nikephoros' wife, Theophano. According to Joannes Zonaras and John Skylitzes, Nikephoros had a loveless relationship with Theophano. He was leading an ascetic life, whereas she was secretly having an affair with Tzimiskes. Theophano and Tzimiskes plotted to overthrow the emperor. On the night of the deed, she left Nikephoros' bedchamber door unlocked, and he was assassinated in his apartment by Tzimiskes and his entourage on 11 December 969.[16] He died praying to the mother of God. Following his death, the Phokas family broke into insurrection under Nikephoros' nephew Bardas Phokas, but their revolt was promptly subdued as Tzimiskes ascended the throne.

Legacy

Contemporary descriptions

The tension between East and West resulting from the policies pursued by Nikephoros may be glimpsed in the unflattering description of him and his court by Bishop Liutprand of Cremona in his Relatio de legatione Constantinopolitana.[33] His description of Nikephoros was clouded by the ill-treatment he received while on a diplomatic mission to Constantinople. Nikephoros, a man of war, was not apt at diplomacy. To add insult to injury, Pope John XIII sent a letter to Nikephoros while Liutprand was in Constantinople calling Otto I Emperor of Rome and even more insultingly referring to Nikephoros merely as Emperor of the Greeks. Liutprand failed in his goal of procuring an Imperial princess as a wife for Otto's young son, the future emperor Otto II.

Bishop Liutprand described Nikephoros as:

- ...a monstrosity of a man, a pygmy, fat-headed and like a mole as to the smallness of his eyes; disgusting with his short, broad, thick, and half hoary beard; disgraced by a neck an inch long; very bristly through the length and thickness of his hair; in color an Ethiopian; one whom it would not be pleasant to meet in the middle of the night; with extensive belly, lean of loin, very long of hip considering his short stature, small of shank, proportionate as to his heels and feet; clad in a garment costly but too old, and foul-smelling and faded through age; shod with Sicyonian shoes; bold of tongue, a fox by nature, in perjury, and lying a Ulysses.[34]

Whereas Bishop Liutprand describes the emperor's hair as being bristly, Leo the Deacon says it was black with "tight curls" and "unusually long".

John Julius Norwich says, about his murder and burial, "It was a honourable place; but Nikephoros Phocas, the White Death of the Saracens, hero of Syria and Crete, saintly and hideous, magnificent and insufferable, had deserved a better end".[35]

Descendants

During the last decades of the tenth century, the Phokades repeatedly tried to get their hands again on the throne, and almost succeeded when Nikephoros' nephew, Bardas Phokas the Younger, rebelled against the rule of Basil II. His death, possibly by cardiac arrest, put an end to the rebellion, and ultimately to the political prominence of the Phokades, although Bardas the Younger's own son, Nikephoros Phokas Barytrachelos, launched another abortive revolt in 1022 along with Nikephoros Xiphias.

Praecepta Militaria

Phokas was the author of a military manual, the Praecepta Militaria.[36][37]

Modern honours

On 19 November 2004, the Hellenic Navy named its tenth Kortenaer-class frigate in his honour as Nikiforos Fokas F-466 (formerly HNLMS Bloys Van Treslong F-824). Also, in the Rethymno regional unit in Crete, a municipality (Nikiforos Fokas) is named after him, as are many streets throughout Greece.

Popular Culture References

Nikephoros II appears as a character in:

- Frederic Harrison, Theophano: The crusade of the tenth century (1904). 978-1017148909

- Frederic Harrison, Nicephorus: A tragedy of New Rome (1906). 978-1290581578

- Anastasia Revi, Byzantium 00AD (Stage play 2000).

- Jonathan Harris, Theosis (2023). 979-8668071487

See also

References

- ↑ Burke, John (2014). I. Nilsson; P. Stephenson (eds.). "Inventing and re-inventing Byzantium: Nikephoros Phokas, Byzantine Studies in Greece, and 'New Rome'". Wanted: Byzantium. The Desire for a Lost Emperor: 5–10.

- ↑ Whittow 1996, p. 9.

- ↑ Krsmanović 2003, Chapter 2: "The Maleinos lineage was among the members of the old byzantine aristocracy, emerging during the 9th century. It was a family of greek origin with close bonds to the region of Asia Minor. It has been presumed that the surname Maleinos is related to the name place Malagina of Bithynia, a location in the theme of Boukellarion during the 9th century. If one accepts that presumption, one should look for the old estates of the family in the fertile valley of the Sangarios river. It is safe, however, to consider the region of Charsianon as the homeland of the family, according to evidence dating back to the end of the 9th century, or the whole of Cappadocia in a wider sense. It is known that the members of the wealthy Maleinos family had estates in the area of jurisdiction of the theme of Charsianon, the wider region of Caesarea of Cappadocia and Ankyra of Galatia."

- ↑ Kazhdan 1991, p. 1276.

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, p. 495.

- ↑ Norwich 1991, pp. 175–178.

- ↑ McMahon 2021, p. 65.

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, pp. 493–495.

- ↑ Norwich 1991, p. 961.

- 1 2 Kaldellis 2017, p. 39.

- ↑ Kaldellis 2017, p. 49.

- ↑ Gregory, Timothy E. (2010). A History of Byzantium. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-5997-8.

- ↑ Kaldellis 2017, p. 41.

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, pp. 498–499.

- ↑ Whittow 1996, pp. 348–349.

- 1 2 Leo the Deacon (c. 1000). History. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 98–143. ISBN 978-0-88402-324-1.

- ↑ Kaldellis 2017, p. 56.

- ↑ PmbZ, al-Ḥasan b. ‘Ammār al-Kalbī (#22562).

- ↑ Brett 2001, p. 242.

- ↑ Keller & Althoff 2008, pp. 221–224.

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, p. 948.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004, pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, pp. 500–501.

- 1 2 Fattori 2013, p. 117.

- ↑ Fattori 2013, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Kaldellis 2017, p. 50.

- 1 2 Fattori 2013, p. 119.

- ↑ Fattori 2013, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Kaldellis 2017, p. 52.

- ↑ McMahon 2016, pp. 22–33.

- ↑ George T. Dennis, Three Byzantine Military Treatises, (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2008), p. 139.

- ↑ Speake, Graham (2018). A history of the Athonite Commonwealth: the spiritual and cultural diaspora of Mount Athos. New York. ISBN 978-1-108-34922-2. OCLC 1041501028.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ H. Mayr-Harting, Liudprand of Cremona’s Account of his Legation to Constantinople (968) and Ottonian Imperial Strategy, English Historical Review (2001), pp. 539–56.

- ↑ Liutprand of Cremona (968), Relatio de legatione Constantinopolitana ad Nicephorum Phocam

- ↑ Norwich 1991, p. 210.

- ↑ Sowing the dragon's teeth : Byzantine warfare in the tenth century. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. 1995. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-88402-224-4.

- ↑ Luttwak, Edward (2009). The grand strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-674-03519-5.

Sources

- Brett, Michael (2001). The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the Fourth Century of the Hijra, Tenth Century CE. The Medieval Mediterranean. Vol. 30. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004117415.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nicephorus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 647–648.

- Dennis, George T. (2008). Three Byzantine Military Treatises. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-339-5.

- Fattori, Niccolò (June 2013). "The Policies of Nikephoros II Phokas in the context of the Byzantine economic recovery" (PDF). Middle East Technical University.

- Garrood, William (2008). "The Byzantine Conquest of Cilicia and the Hamdanids of Aleppo, 959–965". Anatolian Studies. British Institute at Ankara. 58: 127–140. doi:10.1017/s006615460000870x. ISSN 0066-1546. JSTOR 20455416. S2CID 162596738.

- Harris, Jonathan (2020). Introduction to Byzantium, 602–1453. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138556430.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2017). Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-025322-6.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). "Nikephoros II Phocas". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Keller, Hagen; Althoff, Gerd (2008). Die Zeit der späten Karolinger und der Ottonen: 888–1024. Gebhardt Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte Band 3 (in German). Klett-Cotta. ISBN 978-3-608-60003-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2023). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (2nd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-36690-2.

- Kolias, Taxiarchis, "Nicephorus II Focas 963–969, The Military Leader Emperor and his reforms", Vasilopoulos Stefanos D. Athens 1993, ISBN 978-960-7100-65-8, (Worldcat, Greek National Bibliography 1993, Biblionet).

- Krsmanović, Bojana (2003). Φωκάδες. Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor (in Greek). Athens: Foundation of the Hellenic World.

- McMahon, Lucas (2016). "De Velitatione Bellica and Byzantine Guerrilla Warfare". Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU. 22: 22–33.

- McMahon, Lucas (2021). "Logistical modelling of a sea-borne expedition in the Mediterranean: the case of the Byzantine invasion of Crete in AD 960". Mediterranean Historical Review. 36 (1): 65. doi:10.1080/09518967.2021.1900171. S2CID 235676141.

- Ioannes A. Melisseides & Poulcheria Zavolea Melisseidou, "Nikefhoros Phokas (El) Nikfur", ek ton Leontos tou Diakonou, Kedrenou, Aboul Mahasen, Zonara, Ibn El Athir, Glyka, Aboulfeda k.a. Historike Melete, Vol. 1–2, Vergina, Athens 2001, ISBN 978-960-7171-88-7 (Vol. 1) ISBN 978-960-7171-89-4 (Vol. 2), (Worldcat, Greek National Bibliography 2001/2007/2009, Biblionet).

- Norwich, John Julius (1991). Byzantium: The Apogee. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-53779-5.

- Romane, Julian (2015). Byzantium Triumphant. Pen and Sword Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4738-4570-1.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes; Ludwig, Claudia; Pratsch, Thomas; Zielke, Beate (2013). Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit Online. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Nach Vorarbeiten F. Winkelmanns erstellt (in German). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Whittow, Mark (1996). Making of Orthodox Byzantium, 600–1025. Palgrave Macmillan Limited. ISBN 978-0-333-49600-8. OCLC 1050969602.