| Macrinus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

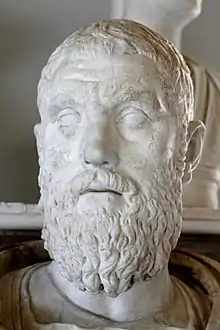

Bust, Capitoline Museums | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 11 April 217 – 8 June 218 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Caracalla | ||||||||

| Successor | Elagabalus | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Diadumenian (218) | ||||||||

| Born | c. 165 Caesarea, Mauretania Caesariensis (now Cherchell, Algeria) | ||||||||

| Died | June 218 (aged 53) Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey) | ||||||||

| Spouse | Nonia Celsa | ||||||||

| Issue | Diadumenian | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Marcus Opellius Macrinus (/məˈkraɪnəs/, mə-CRY-nəs; c. 165 – June 218) was Roman emperor from April 217 to June 218, reigning jointly with his young son Diadumenianus. As a member of the equestrian class, he became the first emperor who did not hail from the senatorial class and also the first emperor who never visited Rome during his reign. Before becoming emperor, Macrinus served under Emperor Caracalla as a praetorian prefect and dealt with Rome's civil affairs. He later conspired against Caracalla and had him murdered in a bid to protect his own life, succeeding him as emperor.

Macrinus was proclaimed emperor of Rome by 11 April 217 while in the eastern provinces of the empire and was subsequently confirmed as such by the Senate; however, for the duration of his reign, he never had the opportunity to return to Rome. His predecessor's policies had left Rome's coffers empty and the empire at war with several kingdoms, including Parthia, Armenia and Dacia. As emperor, Macrinus first attempted to enact reform to bring economic and diplomatic stability to Rome. While Macrinus' diplomatic actions brought about peace with each of the individual kingdoms, the additional monetary costs and subsequent fiscal reforms generated unrest in the Roman military.

Caracalla's aunt Julia Maesa took advantage of the unrest and instigated a rebellion to have her fourteen-year-old grandson, Elagabalus, recognized as emperor. Macrinus was overthrown at the Battle of Antioch on 8 June 218 and Elagabalus proclaimed himself emperor with support from the rebelling Roman legions. Macrinus fled the battlefield and tried to reach Rome, but was captured in Chalcedon and later executed in Cappadocia. He sent his son to the care of Artabanus IV of Parthia, but Diadumenian was also captured before he could reach his destination and executed. After Macrinus' death, the Senate declared him and his son enemies of Rome and had their names struck from the records and their images destroyed; the phrase for such a drastic social/historical erasure came to be damnatio memoriae: damnation (of the) memory (of someone).

Background and career

Macrinus was born in Caesarea (modern Cherchell, Algeria) in the Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis to an equestrian family of Berber origins.[2][3] According to David Potter, his family traced its origins to the Berber tribes of the region and his pierced ear was an indication of his Berber heritage.[4] He received an education which allowed him to ascend to the Roman political class.[5] Over the years, he earned a reputation as a skilled lawyer; and, under Emperor Septimius Severus, he became an important bureaucrat. Severus' successor Caracalla later appointed him a prefect of the Praetorian Guard.[5][6]

While Macrinus probably enjoyed the trust of Emperor Caracalla, this may have changed when, according to tradition, it was prophesied that he would depose and succeed the emperor.[5] Macrinus, fearing for his safety, resolved to have Caracalla murdered before he was condemned.[7]

In the spring of 217, Caracalla was in the eastern provinces preparing a campaign against the Parthian Empire.[8][9] Macrinus was among his staff, as were other members of the Praetorian Guard. In April, Caracalla went to visit a temple of Luna near the site of the battle of Carrhae and was accompanied only by his personal guard, which included Macrinus. On 8 April, while travelling to the temple, Caracalla was stabbed to death by Justin Martialis, a soldier whom Macrinus had recruited to commit the murder.[10] In the aftermath, Martialis was killed by one of Caracalla's men.[8]

For two or three days, Rome remained without an emperor.[10][11] On 11 April, Macrinus proclaimed himself emperor and assumed all of the imperial titles and powers, without waiting for the Senate.[7] The army backed his claim as emperor and the Senate, so far away, was powerless to intervene.[12] Macrinus never returned to Rome as emperor and remained based in Antioch for the duration of his reign.[13] Macrinus was the first emperor to hail from the equestrian class, rather than the senatorial, and also the first emperor of Mauretanian descent.[14] He adopted the name of Severus, in honour of the Severan dynasty, and conferred the imperial title of Augusta to his wife Nonia Celsa[note 1] and the title of Caesar and name of Antoninus to his son Diadumenianus in honour of the Antonine dynasty, thus making him second in command.[14][16][17][18][19] At the time of Diadumenian's accession he was eight years old.[20]

Reign

Despite his equestrian background, Macrinus was accepted by the Senate for two reasons: for the removal of Caracalla, and for having received the loyalty of the army.[10][21] The senators were less concerned by Macrinus' Mauretanian ancestry than by his equestrian social background and scrutinized his actions as emperor. Their opinion of him was reduced by his decisions to appoint to high offices men who were of similarly undistinguished background.[7] Macrinus, not being a senator and having become emperor through force rather than through traditional means, was looked down upon.[10]

Macrinus had several issues that he needed to deal with at the time of his accession, which had been left behind by his predecessor. As Caracalla had a tendency towards military belligerence, rather than diplomacy, this left several conflicts for Macrinus to resolve.[22] Additionally, Caracalla had been a profligate spender of Rome's income.[23] Most of the money was spent on the army; he had greatly increased their pay from 2,000 sesterces to 3,000 sesterces per year.[24][25] The increased expenditures forced Caracalla to strip bare whatever sources of income he had to supply the difference.[23] This shortfall left Rome in a dire fiscal situation that Macrinus needed to address.[23]

Macrinus was at first occupied by the threat of the Parthians, with whom Rome had been at war since the reign of Caracalla. Macrinus settled a peace deal with the Parthians after fighting an indecisive battle at Nisibis in 217.[26] In return for peace, Macrinus was forced to pay a large indemnity to the Parthian ruler Artabanus IV.[27][23] Rome was at the time also under threat from Dacia and Armenia, so any deal with Parthia would likely have been beneficial to Rome.[28] Next, Macrinus turned his attention to Armenia.[29] In 216, Caracalla had imprisoned Khosrov I of Armenia and his family after Khosrov had agreed to meet with Caracalla at a conference to discuss some issue between himself and his sons. Caracalla instead installed a new Roman governor to rule over Armenia. These actions angered the Armenian people and they soon rebelled against Rome.[30][31] Macrinus settled a peace treaty with them by returning the crown and loot to Khosrov's son and successor Tiridates II and releasing his mother from prison, and by restoring Armenia to its status as a client kingdom of Rome.[29] Macrinus made peace with the Dacians by releasing hostages, though this was likely not handled by himself but by Marcius Agrippa.[32] In matters of foreign policy, Macrinus showed a tendency towards settling disputes through diplomacy and a reluctance to engage in military conflict, though this may have been due more to the lack of resources and manpower than to his own personal preference.[22]

Macrinus began to overturn Caracalla's fiscal policies and moved closer towards those that had been set forth by Septimius Severus.[33] One such policy change involved the pay of Roman legionaries. The soldiers that were already enlisted during Caracalla's reign enjoyed exorbitant payments which were impossible for Macrinus to reduce without risking a potential rebellion. Instead, Macrinus allowed the enlisted soldiers to retain their higher payments, but he reduced the pay of new recruits to the level which had been set by Severus.[34][35] Macrinus revalued the Roman currency, increasing the silver purity and weight of the denarius from 50.78 percent and 1.66 grams at the end of Caracalla's reign to 57.85 percent and 1.82 grams from Autumn 217 to the end of his reign, so that it mirrored Severus' fiscal policy for the period 197 to 209.[36][37] Macrinus' goal with these policies might have been to return Rome to the relative economic stability that had been enjoyed under Severus' reign, though it came with a cost.[38] The fiscal changes that Macrinus enacted might have been tenable had it not been for the military. By this time, the strength of the military was too great and by enacting his reforms he angered the veteran soldiers, who viewed his actions in reducing the pay of new recruits as a foreshadowing of eventual reductions in their own privileges and pay. This significantly reduced Macrinus' popularity with the legions that had declared him emperor.[38][39]

Caracalla's mother Julia Domna was initially left in peace when Macrinus became emperor. This changed when Macrinus discovered that she was conspiring against him and had her placed under house arrest in Antioch. By this time Julia Domna was suffering from an advanced stage of breast cancer and soon died in Antioch.[14][40] Afterwards, Macrinus sent Domna's sister Julia Maesa and her children back to Emesa in Syria, from where Maesa set in motion her plans to have Macrinus overthrown.[14][21] Macrinus remained in Antioch instead of going to Rome upon being declared emperor, a step which furthered his unpopularity in Rome and contributed to his eventual downfall.[41]

Downfall

Julia Maesa had retired to her home town of Emesa with an immense fortune, which she had accrued over the course of twenty years. She took her children, Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea, and grandchildren, including Elagabalus, with her to Emesa.[42] Elagabalus, aged 14, was the chief priest of the Phoenician sun-deity Elagabalus (or El-Gabal) in Emesa.[42][43] Soldiers from Legio III Gallica (Gallic Third Legion), that had been stationed at the nearby camp of Raphanea, often visited Emesa and went to see Elagabalus perform his priestly rituals and duties while there.[42][44] Julia Maesa took advantage of this, to suggest to the soldiers that Elagabalus was indeed the illegitimate son of Caracalla.[14][42] On 16 May, Elagabalus was proclaimed emperor by the Legio III Gallica at its camp at Raphanea.[45] Upon Elagabalus' revolt, Macrinus travelled to Apamea and conferred the title of Augustus onto his son, Diadumenianus, and made him co-emperor.[20]

Execution

Macrinus realised that his life was in danger but struggled to decide upon a course of action and remained at Antioch.[46] He sent a force of cavalry commanded by Ulpius Julianus to regain control of the rebels, but they failed and Ulpius died in the attempt. This failure further strengthened Elagabalus' army.[46][6] Soon after, a force under Elagabalus' tutor Gannys marched on Antioch and engaged Macrinus' army on 8 June 218 near the village of Immae, located approximately 24 miles from Antioch.[41] At some point during the ensuing Battle of Antioch, Macrinus deserted the field and returned to Antioch.[41] He was then forced to flee from Antioch as fighting erupted in the city as well.[41] Elagabalus himself subsequently entered Antioch as the new ruler of the Roman Empire.[47] Macrinus fled for Rome; he travelled as far as Chalcedon before being recognized and captured.[48] His son and co-emperor Diadumenianus, sent to the care of Artabanus IV of Parthia, was himself captured in transit at Zeugma and killed in June 218.[14][20][48] Diadumenianus' reign lasted a total of 14 months, and he was about 10 years old when he died.[20] Macrinus, upon learning of his son's death, tried to escape captivity, but he injured himself in the unsuccessful attempt[48] and was afterward executed in Cappadocia; his head was sent to Elagabalus.[48] Much like Macrinus, Diadumenianus' head was also cut off and sent to Elagabalus as a trophy.[19]

Damnatio memoriae

Macrinus and his son Diadumenian were declared hostes, enemies of the state, by the Senate immediately after news had arrived of their deaths and as part of an official declaration of support for the usurper Elagabalus, who was recognized in the Senate as the new Emperor. The declaration of hostes led to two actions being taken against the images of the former Emperors. First, their portraits were destroyed and their names were stricken from inscriptions and papyri. The second action, taken by the Roman soldiers who had rebelled against Macrinus in favour of Elagabalus, was to destroy all of the works and possessions of Macrinus. The damnatio memoriae against Macrinus is among the earliest of such sanctions enacted by the Senate. Many of the marble busts of Macrinus that exist were defaced and mutilated as a response to the damnatio memoriae and many of the coins depicting Macrinus and Diadumenianus were also destroyed. These actions against Macrinus are evidence of his unpopularity in Rome.[18]

Notes

- ↑ The only evidence for her existence is a fictitious letter written in Diadumenianus' biography in the Historia Augusta.[15]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Cooley, p. 496.

- ↑ Naylor, Phillip (2015). North Africa, Revised Edition: A History from Antiquity to the Present. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-76190-2.

- ↑ Michael Grant (1996). The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-415-12772-1.

- ↑ Potter 2004, p. 146.

- 1 2 3 Gibbon 1776, p. 162.

- 1 2 Mennen 2011, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Goldsworthy 2009, p. 75.

- 1 2 Goldsworthy 2009, p. 74.

- ↑ Mennen 2011, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Gibbon 1776, p. 163.

- ↑ Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2.

- ↑ Gibbon 1776, p. 164.

- ↑ Varner, Eric (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. p. 185. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dunstan, William, E. (2010). Ancient Rome. Rowman and Littleman Publishers. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Scott 2008, p. 190.

- ↑ Mennen 2011, p. 26.

- ↑ Crevier, Jean Baptiste Louis (1814). The History of the Roman Emperors From Augustus to Constantine, Volume 8. F. C. & J. Rivington. p. 238.

- 1 2 Varner, Eric (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. pp. 184–188. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

- 1 2 Bunson, Matthew (2014). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-4381-1027-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Vagi 2000, pp. 289–290.

- 1 2 Goldsworthy 2009, pp. 76–77.

- 1 2 Scott 2008, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 Scott 2008, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Dunstan, William, E. (2011). Ancient Rome. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). The Romans, from village to empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 413. ISBN 0-19-511875-8.

- ↑ Scott 2008, p. 76.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2009, p. 88.

- ↑ Scott 2008, p. 111.

- 1 2 Scott 2008, p. 113.

- ↑ Payaslian, S (2008). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. Springer. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-230-60858-0.

- ↑ Scott 2008, pp. 270–271.

- ↑ Scott 2008, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Scott 2008, p. 126.

- ↑ Gibbon 1776, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Scott 2008, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Scott 2008, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Harl, Kenneth. "Roman Currency of the Principate". Tulane University. Archived from the original on 10 February 2001. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 Scott 2008, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Gibbon 1776, p. 166.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2009, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 4 Glanville, Downey (1961). History of Antioch in Syria: From Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Literary Licensing. pp. 248–250. ISBN 1-258-48665-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Gibbon 1776, p. 182.

- ↑ Vagi 2000, pp. 295–296.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2009, p. 77.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2009, p. 78.

- 1 2 Gibbon 1776, p. 169.

- ↑ Icks, Martijn (2011). The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor. I. B. Tauris. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84885-362-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Crevier, Jean Baptiste Louis (1814). The History of the Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine, Volume 8. F. C. & J. Rivington. pp. 236–237.

Sources

- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). The Romans, from village to empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511875-8.

- Bunson, Matthew (2014). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1027-1.

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 496. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- Crevier, Jean Baptiste Louis (1814). The History of the Roman Emperors From Augustus to Constantine. Vol. 8. F. C. & J. Rivington.

- Downey, Glanville. (1961). History of Antioch in Syria: From Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Literary Licensing. ISBN 1-258-48665-2.

- Dunstan, William (2011). Ancient Rome. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7.

- Harl, Kenneth. "Roman Currency of the Principate". Tulane University. Archived from the original on 10 February 2001.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Gibbon, Edward (1776). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 1.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- Icks, Martijn (2011). The Crimes of Elegabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-362-1.

- Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193–284. Impact of Empire. Vol. 12. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9004203594. OCLC 859895124.

- Naylor, Phillip (2015). North Africa, Revised Edition: A History from Antiquity to the Present. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-76190-2.

- Payaslian, S. (2008). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. Springer. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-230-60858-0.

- Potter, David S. (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–392. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10058-5.

- Scott, Andrew (2008). Change and Discontinuity Within the Severan Dynasty: The Case of Macrinus. Rutgers. ISBN 978-0-549-89041-6.

- Vagi, David (2000). Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, C. 82 B.C. – A.D. 480: History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-57958-316-4.

- Varner, Eric (2004). Mutilation and transformation: damnatio memoriae and Roman imperial portraiture. Brill Academic. ISBN 90-04-13577-4.

Further reading

- Dio Cassius. Roman History.

- Herodian History of the Roman Empire.

- Historia Augusta.

- Mattingly, H. (1953) [1951]. "The Reign of Macrinus". In Mylonas, G. E.; Raymond, D. (eds.). Studies Presented to D. M. Robinson on his Seventieth Birthday. St. Louis, MO. pp. 962–969.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Life of Macrinus (Historia Augusta at LacusCurtius: Latin text and English translation)

- "Macrinus and Diadumenianius" at De Imperatoribus Romanis (by Michael Meckler of Ohio State University)

- Macrinus by Dio Cassius

- Livius.org: Marcus Opellius Macrinus