Selected article 1

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/1

Swamps are characterized by slow-moving to stagnant waters. They are usually associated with adjacent rivers or lakes. Swamps are features of areas with very low topographic relief.

Historically, humans have drained swamps to provide additional land for agriculture and to reduce the threat of diseases borne by swamp insects and similar animals. Many swamps have also undergone intensive logging, requiring the construction of drainage ditches and canals. These ditches and canals contributed to drainage and, along the coast, allowed salt water to intrude, converting swamps to marsh or even to open water. Large areas of swamp were therefore lost or degraded. Louisiana provides a classic example of wetland loss from these combined factors. (Full article...)

Selected article 2

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/2

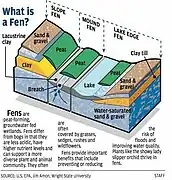

Fens have a characteristic set of plant species, which sometimes provide the best indicators of environmental conditions. For example, fen indicator species in New York State include Carex flava, Cladium mariscoides, Potentilla fruticosa, Pogonia ophioglossoides and Parnassia glauca.

Fens are distinguished from bogs, which are acidic, low in minerals, and usually dominated by sedges and shrubs, along with abundant mosses in the genus Sphagnum. (Full article...)

Selected article 3

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/3

During most years, a vernal pool basin will experience inundation from local surface runoff, followed by desiccation from evapotranspiration. These conditions are commonly associated with Mediterranean climate. Most pools are dry for at least part of the year, and fill with the winter rains or snow melt. Some pools may remain at least partially filled with water over the course of a year or more, but all vernal pools dry up periodically. Some authorities restrict the definition of vernal pools to exclude seasonal wetlands with defined inlet and outlet channels. Such seasonal wetlands have larger drainage basins contributing higher concentrations of dissolved minerals, and increased probability of periodic scouring flows through the wetland. Low dissolved mineral concentrations of smaller vernal pool basins may be characterized as oligotrophic, and poorly buffered with rapid pH shifts due to carbon dioxide uptake during photosynthesis. (Full article...)

Selected article 4

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/4

The substrate is usually organic in nature and may contain peat in varying amounts or be composed entirely of muck. The swamp substrate is typically nutrient-rich and neutral to alkaline but can be acidic and nutrient-poor.

Coniferous swamps vary in composition, with different species of conifer dominating, and varying amounts of deciduous hardwoods growing within the swamp. A wide diversity of plants is represented within the swamps, with certain species dominating in a variety of microhabitats dependent on factors such as available sunlight (as in cases of trees downed by wind or disease), soil Ph, standing groundwater, and differences of elevation within the swamp such as tussocks and nurse logs.

The different types of coniferous swamps are referred to according to their dominant trees. Rich conifer swamp is dominated by Northern white-cedar and typically occurs south of the climatic tension zone throughout the Midwest and northeastern United States and adjacent areas in Canada. North of the climatic tension zone, tamarack (Larix laricina) is the dominant species of conifer in minerotrophic wetlands classified as rich tamarack swamp. A roughly equal mix of hardwood trees and conifers is known as a hardwood-conifer swamp. (Full article...)

Selected article 5

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/5

Marshes provide habitat for many types of plants, animals, and insects that have adapted to living in flooded conditions. The plants must be able to survive in wet mud with low oxygen levels. Many of these plants therefore have aerenchyma, channels within the stem that allow air to move from the leaves into the rooting zone. Marsh plants also tend to have rhizomes for underground storage and reproduction. Familiar examples include cattails, sedges, papyrus and sawgrass. Aquatic animals, from fish to salamanders, are generally able to live with a low amount of oxygen in the water. Some can obtain oxygen from the air instead, while others can live indefinitely in conditions of low oxygen. Marshes provide habitats for many kinds of invertebrates, fish, amphibians, waterfowl and aquatic mammals. Marshes have extremely high levels of biological production, some of the highest in the world, and therefore are important in supporting fisheries. Marshes also improve water quality by acting as a sink to filter pollutants and sediment from the water that flows through them. Marshes (and other wetlands) are able to absorb water during periods of heavy rainfall and slowly release it into waterways and therefore reduce the magnitude of floodin The pH in marshes tends to be neutral to alkaline, as opposed to bogs, where peat accumulates under more acid conditions. (Full article...)

Selected article 6

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/6

There are two types of mire – fens and bogs. A bog is a domed-shaped land form, is higher than the surrounding landscape, and obtains most of its water from rainfall (i.e., is ombrotrophic) while a fen is located on a slope, flat, or depression and gets its water from both rainfall and surface water.

Also, while a bog is always acidic and nutrient-poor, a fen may be either slightly acidic, neutral or alkaline and either nutrient-poor or nutrient-rich. A mire is distinguished from a swamp by its lack of a forest canopy (though some bogs may support limited tree or bush growth, mires are dominated by grass and mosses), and from a marsh by its water nutrients and distribution (marshes are characterized by nutrient-rich stagnant or slow-moving waters; mire waters are located mostly below the soil surface level) as well as its plant life (marsh plants are generally submerged or floating-leaved; those in a mire are not). (Full article...)

Selected article 7

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/7

The region covers an area of about 715,000 km2 (276,000 sq mi), including parts of three Canadian provinces (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Alberta) and five U.S. states (Minnesota, Iowa, North and South Dakota, and Montana).

Few natural surface water drainage systems occur in the region; pothole wetlands are not connected by surface streams. They receive most of their water from spring snowmelt. Some pothole wetlands also receive groundwater inflow, so they typically last longer each year than those that only receive water from precipitation. Shorter-duration wetlands fed only by precipitation typically are sources of groundwater recharge. (Full article...)

Selected article 8

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/8

Unlike a marsh or swamp, a wet meadow does not have standing water present except for brief to moderate periods during the growing season. Instead, the ground in a wet meadow fluctuates between brief periods of inundation and longer periods of saturation. Wet meadows often have large numbers of wetland plant species, which frequently survive as buried seeds during dry periods, and then regenerate after flooding. Wet meadows therefore do not usually support aquatic life such as fish. They typically have a high diversity of plant species, and may attract large numbers of birds, small mammals and insects including butterflies.

Vegetation in a wet meadow usually includes a wide variety of herbaceous species including sedges, rushes, grasses and a wide diversity of other plant species. A few of many possible examples include species of Rhexia, Parnassia, Lobelia, many species of wild orchids (e.g. Calopogon and Spiranthes), and carnivorous plants such as Sarracenia and Drosera. Woody plants if present, account for a minority of the total area cover. High water levels are one of the important factors that prevent invasion by woody plants; in other cases, fire is important. (Full article...)

Selected article 9

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/9

Constructed wetlands are engineered systems that use natural functions of vegetation, soil, and organisms to treat different water streams. Depending on the type of wastewater that has to be treated the system has to be adjusted accordingly which means that pre- or post-treatments might be necessary.

Constructed wetlands can be designed to emulate the features of natural wetlands, such as acting as a biofilter or removing sediments and pollutants such as heavy metals from the water. Some constructed wetlands may also serve as a habitat for native and migratory wildlife, although that is usually not their main purpose.

The two main types of constructed wetlands are subsurface flow and surface flow wetlands. The planted vegetation plays a role in contaminant removal but the filter bed, consisting usually of a combination of sand and gravel, has an equally important role to play. (Full article...)

Selected article 10

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/10

Selected article 11

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/11

.jpg.webp)

Pocosins occur in the Atlantic coastal plain of North America, spanning from southeastern Virginia, through North Carolina, and into South Carolina. However, the majority of pocosins are found in North Carolina. They occupy poorly drained higher ground between streams and floodplains. Seeps cause the inundation. There are often perched water tables underlying pocosins.

Shrub vegetation is common. Pocosins are sometimes called shrub bogs. Pond pines dominate pocosin forests, but loblolly pine and longleaf pine are also associated with pocosins. Additionally, pocosins are home to rare and threatened plant species including Venus flytrap and sweet pitcher plant. (Full article...)

Selected article 12

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/12

This is a woodland that occurs on poorly drained or seasonally wet soils. They are typical of river valley, the surroundings of mires and raised bog, the transition zones between open water and drier ground, and beside small winding streams. Alder, birches and willows are the characteristic trees found in this type of habitat, as they are able to extract oxygen from the water saturated habitat. The UK contains between 50–70,000 hectares (120–172,970 acres).

Wet woodland supports many types of species. E.g. the humidity favours bryophytes (mosses). Alder, birch and willows support many invertebrates: the beetles Melanopion minimum and Rhynchaenus testaceus, the craneflies Lipsothrix errans, Lipsothrix nervosa, and mammals such as otters.

In the UK Woodland Maintenance and Restoration grants are available to protect this type of Woodland under Natural England's Environmental Stewardship Scheme.

Within the British National Vegetation Classification seven types of Wet Woodland are recognised as part of the Woodland and scrub communities in the British National Vegetation Classification system. (Full article...)

Selected article 13

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/13

Riparian zones may be natural or engineered for soil stabilization or restoration. These zones are important natural biofilters, protecting aquatic environments from excessive sedimentation, polluted surface runoff and erosion. They supply shelter and food for many aquatic animals and shade that limits stream temperature change. When riparian zones are damaged by construction, agriculture or silviculture, biological restoration can take place, usually by human intervention in erosion control and revegetation. If the area adjacent to a watercourse has standing water or saturated soil for as long as a season, it is normally termed a wetland because of its hydric soil characteristics. Because of their prominent role in supporting a diversity of species, riparian zones are often the subject of national protection in a Biodiversity Action Plan. These are also known as a "Plant or Vegetation Waste Buffer". (Full article...)

Selected article 14

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/14

Other terms that are used to describe drainage basins are catchment, catchment area, drainage area, river basin and water basin. In North America, the term watershed is commonly used to mean a drainage basin, though in other English-speaking countries, it is used only in its original sense, to mean a drainage divide, the former meaning an area, the latter the high elevation perimeter of that area. Drainage basins drain into other drainage basins in a hierarchical pattern, with smaller sub-drainage basins combining into larger drainage basins.

In closed ("endorheic") drainage basins the water converges to a single point inside the basin, known as a sink, which may be a permanent lake, dry lake, or a point where surface water is lost underground. The drainage basin includes both the streams and rivers that convey the water as well as the land surfaces from which water drains into those channels, and is separated from adjacent basins by a drainage divide. (Full article...)

Selected article 15

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/15

River deltas form when a river carrying sediment reaches either (1) a body of standing water, such as a lake, ocean, or reservoir, (2) another river that cannot remove the sediment quickly enough to stop delta formation, or (3) an inland region where the water spreads out and deposits sediments. The tidal currents also cannot be too strong, as sediment would wash out into the water body faster than the river deposits it. Of course, the river must carry enough sediment to layer into deltas over time. The river's velocity decreases rapidly, causing it to deposit the majority, if not all, of its load. This alluvium builds up to form the river delta. When the flow enters the standing water, it is no longer confined to its channel and expands in width. This flow expansion results in a decrease in the flow velocity, which diminishes the ability of the flow to transport sediment. As a result, sediment drops out of the flow and deposits. Over time, this single channel builds a deltaic lobe (such as the bird's-foot of the Mississippi or Ural river deltas), pushing its mouth into the standing water. As the deltaic lobe advances, the gradient of the river channel becomes lower because the river channel is longer but has the same change in elevation (see slope). (Full article...)

Selected article 16

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/16

Muskeg consists of dead plants in various states of decomposition (as peat), ranging from fairly intact sphagnum moss, to sedge peat, to highly decomposed humus. Pieces of wood can make up five to 15 percent of the peat soil. Muskeg tends to have a water table near the surface. The sphagnum moss forming it can hold 15 to 30 times its own weight in water, allowing the spongy wet muskeg to form on sloping ground. Muskeg patches are ideal habitats for beavers, pitcher plants, agaric mushrooms and a variety of other organisms.

Muskeg forms because permafrost, clay or bedrock prevents water drainage. The water from rain and snow collects, forming permanently waterlogged vegetation and stagnant pools. Muskeg is wet, acidic, and relatively infertile, which prevents large trees from growing, although stunted shore pine, cottonwood, some species of willow, and black spruce are typically found in these habitats. (Full article...)

Selected article 17

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/17

Bayou Country is most closely associated with Cajun and Creole cultural groups native to the Gulf Coast region generally stretching from Houston, Texas, to Mobile, Alabama, and picking back up in South Florida around the Everglades with its center in New Orleans. (Full article...)

Selected article 18

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/18

Palustrine wetlands are one of five categories of wetlands within the Cowardin classification system. The other categories are:

- Marine wetlands, exposed to the open ocean

- Estuarine wetlands, partially enclosed by land and containing a mix of fresh and salt water

- Riverine wetlands, associated with flowing water

- Lacustrine wetlands, associated with a lake or other body of fresh water (Full article...)

Selected article 19

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/19

Under this definition, the salinity of the air and wind is usually high and the meadows are often flooded during and after stormy weather. These conditions implies that the flora is dominated by salt-tolerant species. But that alone does not make a meadow. To be categorized as a meadow in the first place, the plantgrowth has to be low in height, and normally this can only be obtained by traffic or grazing the landscape, either artificially or by livestock. Beach meadows are therefore usually thought of as cultural landscapes or biotopes, requiring some degree of intervention and not being able to sustain itself on its own. If left to their own, beach meadows would transform into a socalled transitional meadow and eventually a shrubby or bushy seashore habitat.

As explained, beach meadows are fundamentally an unstable nature type and this condition have an important influence on the flora and fauna found here. Beach meadows are characterized by a number of plants and animals, that could not have thrived, if the habitat was left to a natural development. The grazing (or traffic) hinders bushes, trees and shrubs to get the upper hand and allows low-growth plants to emerge and dominate. This again attracts and supports a special fauna that would change character, if the beach meadow were left to its own. The specific flora and fauna is of course determined by the general climate and geography of the beach meadow. (Full article...)

Selected article 20

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/20

Salt pannes and pools are unique microhabitats dominated by various species of halophytes, benthic plants and varying estuarine marine life that vary considerably in composition due to a variety of factors including Substrate type: affects the ability of the depression to hold water. (Full article...)

Selected article 21

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/21

Limnology is the study of inland waters. It is often regarded as a division of ecology or environmental science. It covers the biological, chemical, physical, geological, and other attributes of all inland waters (running and standing waters, both fresh and saline, natural or man-made). This includes the study of lakes and ponds, rivers, springs, streams and wetlands. A more recent sub-discipline of limnology, termed landscape limnology, studies, manages, and conserves these aquatic ecosystems using a landscape perspective.Limnology is closely related to aquatic ecology and hydrobiology, which study aquatic organisms in particular regard to their hydrological environment. Although limnology is sometimes equated with freshwater science, this is erroneous since limnology also comprises the study of inland salt lakes.

The term limnology was coined by François-Alphonse Forel (1841–1912) who established the field with his studies of Lake Geneva. Interest in the discipline rapidly expanded, and in 1922 August Thienemann (a German zoologist) and Einar Naumann (a Swedish botanist) co-founded the International Society of Limnology (SIL, from Societas Internationalis Limnologiae). Forel's original definition of limnology, "the oceanography of lakes", was expanded to encompass the study of all inland waters, and influenced Benedykt Dybowski's work on Lake Baikal. (Full article...)

Selected article 22

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/22

Hydrology subdivides into surface water hydrology, groundwater hydrology (hydrogeology), and marine hydrology. Domains of hydrology include hydrometeorology, surface hydrology, hydrogeology, drainage-basin management and water quality, where water plays the central role.

Oceanography and meteorology are not included because water is only one of many important aspects within those fields.

Hydrological research can inform environmental engineering, policy and planning.

Hydrology has been a subject of investigation and engineering for millennia. For example, about 4000 BC the Nile was dammed to improve agricultural productivity of previously barren lands. Mesopotamian towns were protected from flooding with high earthen walls. Aqueducts were built by the Greeks and Ancient Romans, while the history of China shows they built irrigation and flood control works. The ancient Sinhalese used hydrology to build complex irrigation works in Sri Lanka, also known for invention of the Valve Pit which allowed construction of large reservoirs, anicuts and canals which still function. (Full article...)

Selected article 23

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/23

Fisheries are also an extremely important source of protein and income in many wetlands. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, the total catch from inland waters (rivers and wetlands) was 8.7 million metric tonnes in 2002. In addition to food, wetlands supply fibre, fuel and medicinal plants. They also provide valuable ecosystems for birds and other aquatic creatures, help reduce the damaging impact of floods, control pollution and regulate the climate. From economic importance, to aesthetics, the reasons for conserving wetlands have become numerous over the past few decades. (Full article...)

Selected article 24

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/24

The Atchafalaya Basin, the surrounding plain of the river, is filled with bayous, bald cypress swamps, and marshes that give way to more brackish estuarine conditions and end in the Spartina grass marshes, near and at where it meets the Gulf of Mexico. It includes the Lower Atchafalaya River, Wax Lake Outlet, Atchafalaya Bay, and the Atchafalaya River and Bayous Chene, Boeuf, and Black navigation channel. See maps and photo views of the Atchafalaya Deltas centered on 29°26′30″N 91°25′00″W / 29.44167°N 91.41667°W. (Full article...)

Selected article 25

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/25

In the past tidal flats were considered unhealthy, economically unimportant areas and were often dredged and developed into agricultural land.< Several especially shallow mudflat areas, such as the Wadden Sea, are now popular among those practising the sport of mudflat hiking.

On the Baltic Sea coast of Germany in places, mudflats are exposed not by tidal action, but by wind-action driving water away from the shallows into the sea. These wind-affected mudflats are called windwatts in German.

Tidal flats, along with intertidal salt marshes and mangrove forests, are important ecosystems. They usually support a large population of wildlife, and are a key habitat that allows tens of millions of migratory shorebirds to migrate from breeding sites in the northern hemisphere to non-breeding areas in the southern hemisphere. They are often of vital importance to migratory birds, as well as certain species of crabs, mollusks and fish. In the United Kingdom mudflats have been classified as a Biodiversity Action Plan priority habitat. (Full article...)

Selected article 26

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/26

Unlike most ancient human remains, bog bodies have retained their skin and internal organs due to the unusual conditions of the surrounding area. These conditions include highly acidic water, low temperature, and a lack of oxygen, and combine to preserve but severely tan their skin. While the skin is well-preserved, the bones are generally not, due to the acid in the peat having dissolved the calcium phosphate of bone.

The oldest known bog body is the skeleton of Koelbjerg Woman from Denmark, who has been dated to 8000 BCE, during the Mesolithic period. The oldest fleshed bog body is that of Cashel Man, who dates to 2000 BCE during the Bronze Age. (Full article...)

Selected article 27

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/27

Human habitation in the southern portion of the Florida peninsula dates to 15,000 years ago. Before European colonization, the region was dominated by the native Calusa and Tequesta tribes. With Spanish colonization, both tribes declined gradually during the following two centuries. The Seminole formed from mostly Creek people who had been warring to the North; they assimilated other peoples and created a new culture. After being forced from northern Florida into the Everglades during the Seminole Wars of the early 19th century, they were able to resist removal by the United States Army. They adapted to the region. (Full article...)

Selected article 28

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/28

For many years the swamp, and especially its thicket of vegetation, proved an impenetrable barrier to navigation along the Nile. For this reason, the search for the source of the Nile was particularly difficult; it eventually involved overland expeditions from the central African coast, so as to avoid having to travel through the Sudd.

The Sudd stretches from Mongalla to just outside the Sobat confluence with the White Nile just upstream of Malakal as well as westwards along the Bahr el Ghazal. The shallow and flat inland delta lies between 5.5 and 9.5 degrees latitude North and covers an area of 500 kilometres (310 mi) south to north and 200 kilometres (120 mi) east to west between Mongalla in the south and Malakal in the north.

Sudd was designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance on 5 June 2006. (Full article...)

Selected article 29

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/29

Bog-wood, also known as abonos and morta, especially amongst pipesmokers, is a material from trees that have been buried in peat bogs and preserved from decay by the acidic and anaerobic bog conditions, sometimes for hundreds or even thousands of years. The wood is usually stained brown by tannins dissolved in the acidic water. Bog-wood represents the early stages in the fossilisation of wood, with further stages ultimately forming lignite and coal over a period of many millions of years. Bog-wood may come from any tree species naturally growing near or in bogs, including oak (Quercus – "bog oak"), pine (Pinus), yew (Taxus), swamp cypress (Taxodium) and kauri (Agathis). Bog-wood is often removed from fields etc. and placed in clearance cairns. It is a rare form of timber that is "comparable to some of the world's most expensive tropical hardwoods".Soils that are mostly wet, sandy, gravel and clay-like -- usually found above high underground waters -- are the most suitable habitats for oak forest. These forests thrive best on lowland and slight upland soils of the diluvial geological era, the valleys of river basins being especially suitable sites for this type of oak.

Variations in the water level, floods, marshes formation promote the growth of oak trees. Because of a continuous change of the direction of the river flow on a greater or lesser degree, the mainstreams weave through the valleys constantly forming live meanders. In its meandering course, the river undermines the banks covered with trees, which fall into the river and are swept away in the water. When the trunk gets trapped by its branches and roots in the river bed, over time layers of mud, sand and gravel cover it. Deprived of oxygen the wood undergoes the process of fossilization and a long process of morta formation. (Full article...)

Selected article 30

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/30

Oases are formed from underground rivers or aquifers such as an artesian aquifer, where water can reach the surface naturally by pressure or by man-made wells. Occasional brief thunderstorms provide subterranean water to sustain natural oases, such as the Tuat. Substrata of impermeable rock and stone can trap water and retain it in pockets, or on long faulting subsurface ridges or volcanic dikes water can collect and percolate to the surface. Any incidence of water is then used by migrating birds, which also pass seeds with their droppings which will grow at the water's edge forming an oasis. (Full article...)

Selected article 31

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/31

Flood plains are made by a meander eroding sideways as it travels downstream. When a river breaks its banks and floods, it leaves behind layers of alluvium (silt). These gradually build up to create the floor of the flood plain. Floodplains generally contain unconsolidated sediments, often extending below the bed of the stream. These are accumulations of sand, gravel, loam, silt, and/or clay, and are often important aquifers, the water drawn from them being pre-filtered compared to the water in the river. (Full article...)

Selected article 32

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/32

The Indiana Dunes contain interdunal wetlands. Many conservation efforts have been made to preserve parts of the Indiana Dunes.

Because they are typically very shallow, interdunal wetlands warm quickly, and provide an abundant source of invertebrates eaten by many species of shorebirds. Many interdunal wetlands are ephemeral, drying out during periods of low rain or low water.

In the Great Lakes region of North America, interdunal communities are typically mildly calcareous and dominated by rushes, sedges and shrubs. They are tentatively classified as G2, or globally imperiled, under the NatureServe rankings.

A distinction is sometimes made between interdunal and intradunal wetlands such as pannes, which form within a single dune as part of a blowout. (Full article...)

Selected article 33

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/33

In a river estuary, large amounts of silt are deposited by the ebbing tides and inflowing rivers.

The earliest plant colonizers are algae and eel grass, which can tolerate submergence by the tide for most of the 12-hour cycle and which trap mud, causing it to accumulate. Two other colonizers are Salicornia and Spartina, which are halophytes, i.e. plants that can tolerate saline conditions. They grow on the inter-tidal mudflats with a maximum of four hours' exposure to air every 12 hours.

Spartina has long roots enabling it to trap more mud than the initial colonizing plants and Salicornia, and so on. In most places this becomes dominant vegetation. The initial tidal flats receive new sediments daily, are waterlogged to the exclusion of oxygen, and have a high pH value.

The sward zone, in contrast, is inhabited by plants that can only tolerate a maximum of four hours submergence every day (24 hours). The dominant species there are sea lavender and other numerous types of grasses. (Full article...)

Selected article 34

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/34

Roughly 80% of the Pantanal floodplains are submerged during the rainy seasons, nurturing an astonishing biologically diverse collection of aquatic plants and helping to support a dense array of animal species.

The name "Pantanal" comes from the Portuguese word pântano, meaning wetland, bog, swamp, quagmire or marsh. By comparison, the Brazilian highlands are locally referred to as the planalto, plateau or, literally, high plain. (Full article...)

Selected article 35

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/35

Peatlands, also known as mires, particularly bogs, are the most important source of peat, but other less common wetland types also deposit peat, including fens, pocosins, and peat swamp forests. Other words for lands dominated by peat include moors or muskegs. Landscapes covered in peat also have specific kinds of plants, particularly Sphagnum moss, ericaceous shrubs, and sedges (see bog for more information on this aspect of peat). Since organic matter accumulates over thousands of years, peat deposits also provide records of past vegetation and climates stored in plant remains, particularly pollen. Hence, they allow humans to reconstruct past environments and changes in human land use. (Full article...)

Selected article 36

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/36

Mangroves are salt tolerant trees, also called halophytes, and are adapted to life in harsh coastal conditions. They contain a complex salt filtration system and complex root system to cope with salt water immersion and wave action. They are adapted to the low oxygen (anoxic) conditions of waterlogged mud.

The word is used in at least three senses: (1) most broadly to refer to the habitat and entire plant assemblage or mangal, for which the terms mangrove forest biome, mangrove swamp and mangrove forest are also used, (2) to refer to all trees and large shrubs in the mangrove swamp, and (3) narrowly to refer to the mangrove family of plants, the Rhizophoraceae, or even more specifically just to mangrove trees of the genus Rhizophora.

The mangrove biome, or mangal, is a distinct saline woodland or shrubland habitat characterized by depositional coastal environments, where fine sediments (often with high organic content) collect in areas protected from high-energy wave action. The saline conditions tolerated by various mangrove species range from brackish water, through pure seawater (30 to 40 ppt [parts per thousand]), to water concentrated by evaporation to over twice the salinity of ocean seawater (up to 90 ppt). (Full article...)

Selected article 37

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/37

The principal factor controlling the distribution of aquatic plants is the depth and duration of flooding. However, other factors may also control their distribution, abundance, and growth form, including nutrients, disturbance from waves, grazing, and salinity.

Aquatic vascular plants have originated on multiple occasions in different plant families; they can be ferns or angiosperms (including both monocots and dicots). Seaweeds are not vascular plants; rather they are multicellular marine algae, and therefore are not typically included among aquatic plants. A few aquatic plants are able to survive in brackish, saline, and salt water. Examples are found in genera such as Thalassia and Zostera. Although most aquatic plants can reproduce by flowering and setting seed, many also have extensive asexual reproduction by means of rhizomes, turions, and fragments in general. (Full article...)

Selected article 38

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/38

In response to floods caused by hurricanes in 1947, the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project (C&SF) was established to construct flood control devices in the Everglades. The C&SF built 1,400 miles (2,300 km) of canals and levees between the 1950s and 1971 throughout South Florida. Their last venture was the C-38 canal, which straightened the Kissimmee River and caused catastrophic damage to animal habitats, adversely affecting water quality in the region. The canal became the first C&SF project to revert when the 22-mile (35 km) canal began to be backfilled, or refilled with the material excavated from it, in the 1980s. (Full article...)

Selected article 39

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/39

Bog butter is found buried inside some sort of wooden container, such as buckets, kegs, barrels, dishes and butter churns. It is of animal origin, and is also known as butyrellite. Until 2003 scientists and archaeologists were not quite sure of the origin of bog butter. Scientists working at the University of Bristol discovered that some samples of the "butter" were of adipose/tallow origin while others were of dairy origin.

In Scotland, the practice of burying bog butter dates back to at least the 2nd or 3rd century. Until recently, Ireland's oldest recorded find of bog butter was a carved hanging bowl dating back to the 6th or 7th century AD. On 28 April 2011, there were press reports of a find of approximately 50 kilograms (110 lb) of bog butter in Tullamore, County Offaly, thought to date back about five millennia. Found in a carved wooden vessel 0.3 metres (0.98 ft) in diameter and 0.6 metres (2.0 ft) in height, it was buried at a depth of 2.3 metres (7.5 ft), and still bore a faint smell of dairy. (Full article...)

Selected article 40

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/40

Iron-bearing groundwater typically emerges as a spring. The iron is oxidized to ferric hydroxide upon encountering the oxidizing environment of the surface. Bog ore often combines goethite, magnetite and vugs or stained quartz. Oxidation may occur through enzyme catalysis by iron bacteria. It is not clear whether the magnetite precipitates upon first contact with oxygen, then oxidizes to ferric compounds, or whether the ferric compounds are reduced when exposed to anoxic conditions upon burial beneath the sediment surface and reoxidized upon exhumation at the surface.

Iron made from bog ore will often contain residual silicates, which can form a glassy coating that grants some resistance to rusting.

Iron smelting from bog iron was invented during the Pre-Roman Iron Age, and most Viking era iron was smelted from bog iron. The bog iron deposits of Northern and Northeastern Europe were created after the Ice Age ended, on postglacial plains. In Russia, bog ore was the principal source of iron until the 16th century, when the superior ores of Ural Mountains became available. (Full article...)

Selected article 41

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/41

An invasive species is a plant, fungus, or animal species that is not native to a specific location (an introduced species), and which has a tendency to spread to a degree believed to cause damage to the environment, human economy or human health.One study pointed out widely divergent perceptions of the criteria for invasive species among researchers and concerns with the subjectivity of the term "invasive." Some of the alternate usages of the term are below:

- The term as most often used applies to introduced species (also called "non-indigenous" or "non-native") that adversely affect the habitats and bioregions they invade economically, environmentally, or ecologically. Such invasive species may be either plants or animals and may disrupt by dominating a region, wilderness areas, particular habitats, or wildland-urban interface land from loss of natural controls (such as predators or herbivores). This includes non-native invasive plant species labeled as exotic pest plants and invasive exotics growing in native plant communities. It has been used in this sense by government organizations as well as conservation groups such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the California Native Plant Society. The European Union defines "Invasive Alien Species" as those that are, firstly, outside their natural distribution area, and secondly, threaten biological diversity. It is also used by land managers, botanists, researchers, horticulturalists, conservationists, and the public for noxious weeds. The kudzu vine, Andean Pampas grass (Cortaderia jubata), and yellow starthistle are examples. (Full article...)

Selected article 42

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/42

Lake ecosystems are a prime example of lentic ecosystems. Lentic refers to stationary or relatively still water, from the Latin lentus, which means sluggish. Lentic waters range from ponds to lakes to wetlands, and much of this article applies to lentic ecosystems in general. Lentic ecosystems can be compared with lotic ecosystems, which involve flowing terrestrial waters such as rivers and streams. Together, these two fields form the more general study area of freshwater or aquatic ecology.

Lentic systems are diverse, ranging from a small, temporary rainwater pool a few inches deep to Lake Baikal, which has a maximum depth of 1740 m. The general distinction between pools/ponds and lakes is vague, but Brown states that ponds and pools have their entire bottom surfaces exposed to light, while lakes do not. In addition, some lakes become seasonally stratified (discussed in more detail below.) Ponds and pools have two regions: the pelagic open water zone, and the benthic zone, which comprises the bottom and shore regions. Since lakes have deep bottom regions not exposed to light, these systems have an additional zone, the profundal. These three areas can have very different abiotic conditions and, hence, host species that are specifically adapted to live there. (Full article...)

Selected article 43

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/43

Known as "Aapa" moore (from Finnish aapasuo) or Strangemoore in Northern Europe.

A string bog has a pattern of narrow (2–3m wide), low (<1m high) ridges oriented at right angles to the direction of drainage with wet depressions or pools occurring between the ridges. The water and peat are very low in nutrients because the water has been derived from other ombrotrophic wetlands, which receive all of their water and nutrients from precipitation, rather than from streams or springs. The peat thickness is >1m.

String bogs are features associated with periglacial climates, where the temperature results in long periods of subzero temperatures. The active layer exists as frozen ground for long periods and melts in the spring thaw. Such slow melting results in characteristic mass movement processes and features exclusively associated with specific periglacial environments. (Full article...)

Selected article 44

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/44

Moorland habitats are most extensive in the neotropics and tropical Africa but also occur in northern and western Europe, Northern Australia, North America, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Most of the world's moorlands are very diverse ecosystems. In the extensive moorlands of the tropics biodiversity can be extremely high. Moorland also bears a relationship to tundra (where the subsoil is permafrost or permanently frozen soil), appearing as the tundra retreats and inhabiting the area between the permafrost and the natural tree zone. The boundary between tundra and moorland constantly shifts with climate change. (Full article...)

Selected article 45

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/45

The thermal stratification of lakes refers to a change in the temperature at different depths in the lake, and is due to the change in water's density with temperature. Cold water is denser than warm water and the epilimnion generally consists of water that is not as dense as the water in the hypolimnion. However, the temperature of maximum density for freshwater is 4 °C. In temperate regions where lake water warms up and cools through the seasons, a cyclical pattern of overturn occurs that is repeated from year to year as the cold dense water at the top of the lake sinks. For example, in dimictic lakes the lake water turns over during the spring and the fall. This process occurs more slowly in deeper water and as a result, a thermal bar may form. If the stratification of water lasts for extended periods, the lake is meromictic. Conversely, for most of the time, the relatively shallower meres are unstratified; that is, the mere is considered all epilimnion.

The accumulation of dissolved carbon dioxide in three meromictic lakes in Africa (Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun in Cameroon and Lake Kivu in Rwanda) is potentially dangerous because if one of these lakes is triggered into limnic eruption, a very large quantity of carbon dioxide can quickly leave the lake and displace the oxygen needed for life by people and animals in the surrounding area. (Full article...)

Selected article 46

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/46

The word once included the sea or an arm of the sea, in its range of meaning but this marine usage is now obsolete (OED). It is a poetical or dialect word meaning a sheet of standing water, a lake or a pond (OED). The OED's fourth definition ("A marsh, a fen.") includes wetland such as fen amongst usages of the word which is reflected in the lexicographers' recording of it. In a quotation from the year 598, mere is contrasted against moss (bog) and field against fen. The OED quotation from 1609 does not say what a mere is, except that it looks black. In 1629 mere and marsh were becoming interchangeable but in 1876 mere was 'heard, at times, applied to ground permanently under water': in other words, a very shallow lake.

Where land similar to that of Martin Mere, gently undulating glacial till, becomes flooded and develops fen and bog, the remnants of the original mere remain until the whole is filled with peat. This can be delayed where the mere is fed by lime-rich water from chalk or limestone upland and a significant proportion of the outflow from the mere takes the form of evaporation. (Full article...)

Selected article 47

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/47

Kettles are fluvioglacial landforms occurring as the result of blocks of ice calving from the front of a receding glacier and becoming partially to wholly buried by glacial outwash. Glacial outwash is generated when streams of meltwater flow away from the glacier and deposit sediment to form broad outwash plains called sandurs. When the ice blocks melt, kettle holes are left in the sandur. When the development of numerous kettle holes disrupt sandur surfaces, a jumbled array of ridges and mounds form, resembling kame and kettle topography.

Kettle holes can form as the result of floods caused by the sudden drainage of an ice-dammed lake. These floods, called jökulhlaups, often rapidly deposit large quantities of sediment onto the sandur surface. The kettle holes are formed by the melting blocks of sediment-rich ice that were transported and consequently buried by the jökulhlaups. It was found in field observations and laboratory simulations done by Maizels in 1992 that ramparts form around the edge of kettle holes generated by jökulhlaups. The development of distinct types of ramparts depends on the concentration of rock fragments contained in the melted ice block and on how deeply the block was buried by sediment. (Full article...)

Selected article 48

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/48

Várzea forests can be split into two categories: low várzea and high várzea. Low várzea forests can be categorized by lower lying areas where the annual water column has an average height of more than 3 meters, where the period of flooding is greater than 50 days per year. High várzea forests are categorized as the areas where the average annual water column is less than 3 meters high and flooding periods are less than 50 days per year. Amazonian várzea forests are flooded by nutrient rich, high sediment white water rivers such as the Solimões-Amazon, the Purus, and Madeira rivers. This makes the várzea areas distinct from igapós, floodplains from nutrient poor black water. The water level fluctuations that the várzea experiences result in distinct aquatic and terrestrial phases within the year. Amazonian white water river floodplains cover an area of more than 300,000 km2, and várzea forests cover approximately 180,000 km2 of the Amazon basin. 68% of the Amazonian river basin is located in Brazil, with the remaining areas located in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Peru, Suriname, and Guyana. The várzea extends from this basin upward into the land before reaching slopes into the terra firme forests. (Full article...)

Selected article 49

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/49

The wetland indicator status of a species is based upon the individual species occurrence in wetlands in 13 separate regions within the United States. In some instances the specified regions contain all or part of different floristic provinces and the tension zones which occur between them.

While many Obligate Wetland (OBL) species do occur in permanently or semi-permanently flooded wetlands, there are also a number of obligates that occur in and temporary or seasonally flooded wetlands. A few species are restricted entirely to these transient-type wetland environments.

Plant species are general indicators of various degrees of environmental factors; they are however not precise. The presence of a plant species at a specific site depends on a variety of climatic, edaphic and biotic factors, and the effect of individual factors such as degree of substrate saturation and depth and duration of standing water is impossible to isolate. (Full article...)

Selected article 50

Portal:Wetlands/Selected article/50

In the Southern Hemisphere they are less well-developed due to the relatively low latitudes of the main land areas, though similar environments are reported in Patagonia, the Falkland Islands and New Zealand. The blanket bogs known as 'featherbeds' on subantarctic Macquarie Island occur on raised marine terraces; they may be up to 5 m deep, tremble or quake when walked on and can be hazardous to cross. It is doubtful whether the extremely impoverished flora of Antarctica is sufficiently well developed to be considered as blanket bogs.

In some areas of Europe, the spread of blanket bogs is traced to deforestation by prehistoric cultures. In many areas peat is cultivated as a fossil fuel and used either in electricity generation or domestic solid fuel for heating. In the Republic of Ireland, a state owned agency, Bord na Móna, owns large areas of bog land and harvests peat for electricity generation but that peat is mainly from the raised bogs in the central plains. Bord na Móna used to burn peat in the peat fired generating station at Bellacorick but that closed down many years ago and the area now houses a large windfarm.

Some blanket bogs are now preserved by government organisations in both Ireland and Britain, as this habitat is now under threat from extensive harvesting. Examples of protected blanket bogs include Sliabh Beagh, Bellacorick and Airds Moss. (Full article...)