| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sojourn, Ultane, Sevorane, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Inhaled |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver by CYP2E1 |

| Metabolites | Hexafluoroisopropanol |

| Elimination half-life | 15–23 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.171.146 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

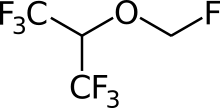

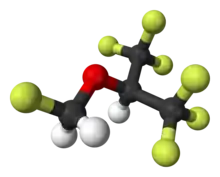

| Formula | C4H3F7O |

| Molar mass | 200.056 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.53 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 58.5 °C (137.3 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Sevoflurane, sold under the brand name Sevorane, among others, is a sweet-smelling, nonflammable, highly fluorinated methyl isopropyl ether used as an inhalational anaesthetic for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. After desflurane, it is the volatile anesthetic with the fastest onset.[2] While its offset may be faster than agents other than desflurane in a few circumstances, its offset is more often similar to that of the much older agent isoflurane. While sevoflurane is only half as soluble as isoflurane in blood, the tissue blood partition coefficients of isoflurane and sevoflurane are quite similar. For example, in the muscle group: isoflurane 2.62 vs. sevoflurane 2.57. In the fat group: isoflurane 52 vs. sevoflurane 50. As a result, the longer the case, the more similar will be the emergence times for sevoflurane and isoflurane.[3][4][5]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6]

Medical uses

It is one of the most commonly used volatile anesthetic agents, particularly for outpatient anesthesia,[7] across all ages, as well as in veterinary medicine. Together with desflurane, sevoflurane is replacing isoflurane and halothane in modern anesthesia practice. It is often administered in a mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen.

Physiological effects

Sevoflurane is a potent vasodilator, as such it induces a dose dependent reduction in blood pressure and cardiac output. It is a bronchodilator, however, in patients with pre-existing lung pathology it may precipitate coughing and laryngospasm. It reduces the ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia and impedes hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Sevoflurane vasodilatory properties also cause it to increase intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow. However, it reduces cerebral metabolic rate. [8][9]

Adverse effects

Sevoflurane has an excellent safety record,[7] but is under review for potential hepatotoxicity, and may accelerate Alzheimer's.[10] There were rare reports involving adults with symptoms similar to halothane hepatotoxicity.[7] Sevoflurane is the preferred agent for mask induction due to its lesser irritation to mucous membranes.

Sevoflurane is an inhaled anaesthetic that is often used to induction and maintenance of anaesthesia in children for surgery.[11] During the process of awakening from the medication, it has been associated with a high incidence (>30%) of agitation and delirium in preschool children undergoing minor noninvasive surgery.[11] It is not clear if this can be prevented.[11]

Studies examining a current significant health concern, anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity (including with sevoflurane, and especially with children and infants) are "fraught with confounders, and many are underpowered statistically", and so are argued to need "further data... to either support or refute the potential connection".[12]

Concern regarding the safety of anaesthesia is especially acute with regard to children and infants, where preclinical evidence from relevant animal models suggest that common clinically important agents, including sevoflurane, may be neurotoxic to the developing brain, and so cause neurobehavioural abnormalities in the long term; two large-scale clinical studies (PANDA and GAS) were ongoing as of 2010, in hope of supplying "significant [further] information" on neurodevelopmental effects of general anaesthesia in infants and young children, including where sevoflurane is used.[13]

In 2021, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital published in Communications Biology research that sevoflurane may accelerate existing Alzheimer's or existing tau protein to spread: "These data demonstrate anesthesia-associated tau spreading and its consequences. [...] This tau spreading could be prevented by inhibitors of tau phosphorylation or extracellular vesicle generation." According to Neuroscience News, "Their previous work showed that sevoflurane can cause a change (specifically, phosphorylation, or the addition of phosphate) to tau that leads to cognitive impairment in mice. Other researchers have also found that sevoflurane and certain other anesthetics may affect cognitive function."[10]

Additionally, there has been some investigation into potential correlation of sevoflurane use and renal damage (nephrotoxicity).[14] However, this should be subject to further investigation, as a recent study shows no correlation between sevoflurane use and renal damage as compared to other control anesthetic agents.[15]

Pharmacology

The exact mechanism of the action of general anaesthetics has not been delineated.[16] Sevoflurane acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor in electrophysiology studies of neurons and recombinant receptors.[17][18][19][20] However, it also acts as an NMDA receptor antagonist,[21] potentiates glycine receptor currents,[20] and inhibits nAChR[22] and 5-HT3 receptor currents.[23][24][25]

History

Sevoflurane was discovered by Ross Terrell[26] and independently by Bernard M Regan. A detailed report of its development and properties appeared in 1975 in a paper authored by Richard Wallin, Bernard Regan, Martha Napoli and Ivan Stern. It was introduced into clinical practice initially in Japan in 1990 by Maruishi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Osaka, Japan. The rights for sevoflurane worldwide were held by AbbVie. It is now available as a generic drug.

Global-warming potential

Sevoflurane is a greenhouse gas. The twenty-year global-warming potential, GWP(20), for sevoflurane is 349.[27]

Degradation of Sevoflurane

Sevoflurane will degrade into what is most commonly referred to as compound A (fluoromethyl 2,2-difluoro-1-(trifluoromethyl)vinyl ether) when in contact with CO2 absorbents, and this degradation tends to enhance with decreased fresh gas flow rates, increased temperatures, and increased sevoflurane concentration.[28] Compound A is what some believe is in correlation with renal damage.[29]

References

- ↑ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ↑ Sakai EM, Connolly LA, Klauck JA (December 2005). "Inhalation anesthesiology and volatile liquid anesthetics: focus on isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane". Pharmacotherapy. 25 (12): 1773–1788. doi:10.1592/phco.2005.25.12.1773. PMID 16305297. S2CID 40873242.

- ↑ Maheshwari K, Ahuja S, Mascha EJ, Cummings KC, Chahar P, Elsharkawy H, et al. (February 2020). "Effect of Sevoflurane Versus Isoflurane on Emergence Time and Postanesthesia Care Unit Length of Stay: An Alternating Intervention Trial". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 130 (2): 360–366. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004093. PMID 30882520.

- ↑ Sloan MH, Conard PF, Karsunky PK, Gross JB (March 1996). "Sevoflurane versus isoflurane: induction and recovery characteristics with single-breath inhaled inductions of anesthesia". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 82 (3): 528–532. doi:10.1213/00000539-199603000-00018. PMID 8623956.

- ↑ Smith I, Ding Y, White PF (February 1992). "Comparison of induction, maintenance, and recovery characteristics of sevoflurane-N2O and propofol-sevoflurane-N2O with propofol-isoflurane-N2O anesthesia". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 74 (2): 253–259. doi:10.1213/00000539-199202000-00015. PMID 1731547. S2CID 12345796.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- 1 2 3 "Drug Record: Sevoflurane". Livertox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. 2 July 2014. PMID 31643176. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ Edgington TL, Muco E, Maani CV (2022). "Sevoflurane". StatPearls. PMID 30521202.

- ↑ Green WB (December 1995). "The ventilatory effects of sevoflurane". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 81 (6 Suppl): S23–S26. doi:10.1097/00000539-199512001-00004. PMID 7486144.

- 1 2 "Anesthetic May Affect Tau Spread in the Brain to Promote Alzheimer's Disease Pathology". Neuroscience News. 2021-05-16. Retrieved 2021-05-17.

- 1 2 3 Costi D, Cyna AM, Ahmed S, Stephens K, Strickland P, Ellwood J, et al. (September 2014). "Effects of sevoflurane versus other general anaesthesia on emergence agitation in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD007084. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007084.pub2. PMID 25212274.

- ↑ Vlisides P, Xie Z (2012). "Neurotoxicity of general anesthetics: an update". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 18 (38): 6232–6240. doi:10.2174/138161212803832344. PMID 22762477.

- ↑ Sun L (December 2010). "Early childhood general anaesthesia exposure and neurocognitive development". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 105 (Suppl 1): i61–i68. doi:10.1093/bja/aeq302. PMC 3000523. PMID 21148656.

- ↑ Edgington TL, Muco E, Naani CV (2023). "Sevoflurane". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30521202. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ↑ Sondekoppam RV, Narsingani KH, Schimmel TA, McConnell BM, Buro K, Özelsel TJ (November 2020). "The impact of sevoflurane anesthesia on postoperative renal function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials". Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia = Journal Canadien d'Anesthesie. 67 (11): 1595–1623. doi:10.1007/s12630-020-01791-5. PMID 32812189.

- ↑ Perkins B (7 February 2005). "How does anesthesia work?". Scientific American. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ↑ Jenkins A, Franks NP, Lieb WR (February 1999). "Effects of temperature and volatile anesthetics on GABA(A) receptors". Anesthesiology. 90 (2): 484–491. doi:10.1097/00000542-199902000-00024. PMID 9952156.

- ↑ Wu J, Harata N, Akaike N (November 1996). "Potentiation by sevoflurane of the gamma-aminobutyric acid-induced chloride current in acutely dissociated CA1 pyramidal neurones from rat hippocampus". British Journal of Pharmacology. 119 (5): 1013–1021. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15772.x. PMC 1915958. PMID 8922750.

- ↑ Krasowski MD, Harrison NL (February 2000). "The actions of ether, alcohol and alkane general anaesthetics on GABAA and glycine receptors and the effects of TM2 and TM3 mutations". British Journal of Pharmacology. 129 (4): 731–743. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703087. PMC 1571881. PMID 10683198.

- 1 2 Schüttler J, Schwilden H (8 January 2008). Modern Anesthetics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-3-540-74806-9.

- ↑ Brosnan RJ, Thiesen R (June 2012). "Increased NMDA receptor inhibition at an increased Sevoflurane MAC". BMC Anesthesiology. 12 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/1471-2253-12-9. PMC 3439310. PMID 22672766.

- ↑ Van Dort CJ (2008). Regulation of Arousal by Adenosine A(1) and A(2A) Receptors in the Prefrontal Cortex of C57BL/6J Mouse. University of Michigan. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-549-99431-2.

- ↑ Schüttler J, Schwilden H (8 January 2008). Modern Anesthetics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-3-540-74806-9.

- ↑ Suzuki T, Koyama H, Sugimoto M, Uchida I, Mashimo T (March 2002). "The diverse actions of volatile and gaseous anesthetics on human-cloned 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesiology. 96 (3): 699–704. doi:10.1097/00000542-200203000-00028. PMID 11873047. S2CID 6705116.

- ↑ Hang LH, Shao DH, Wang H, Yang JP (2010). "Involvement of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptors in sevoflurane-induced hypnotic and analgesic effects in mice". Pharmacological Reports. 62 (4): 621–626. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.587.5552. doi:10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70319-4. PMID 20885002. S2CID 4754446.

- ↑ Burns WB, Eger EI (August 2011). "Ross C. Terrell, PhD, an anesthetic pioneer". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 113 (2): 387–389. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3182222b8a. PMID 21642612. S2CID 19988772.

- ↑ Ryan SM, Nielsen CJ (July 2010). "Global warming potential of inhaled anesthetics: application to clinical use". Anesthesia and Analgesia. International Anesthesia Research Society. 111 (1): 92–98. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181e058d7. PMID 20519425. S2CID 20737354.

- ↑ "Carbon Dioxide Absorbent - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ↑ Eger EI, Koblin DD, Bowland T, Ionescu P, Laster MJ, Fang Z, et al. (January 1997). "Nephrotoxicity of sevoflurane versus desflurane anesthesia in volunteers". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 84 (1): 160–168. doi:10.1213/00000539-199701000-00029. PMID 8989018.

Further reading

- Patel SS, Goa KL (April 1996). "Sevoflurane. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its clinical use in general anaesthesia". Drugs. 51 (4): 658–700. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651040-00009. PMID 8706599. S2CID 265731583. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

Haria M, Bryson HM, Goa KL, Patel SS (August 1996). "Erratum". Drugs. 52 (2): 253. doi:10.1007/bf03257493. - Wallin RF, Regan BM, Napoli MD, Stern IJ (Nov–Dec 1975). "Sevoflurane: a new inhalational anesthetic agent". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 54 (6): 758–766. doi:10.1213/00000539-197511000-00021. PMID 1239214. S2CID 26832938.