The "Four Policemen" was a postwar council with the Big Four that US President Franklin Roosevelt proposed as a guarantor of world peace. Their members were called the Four Powers during World War II and were the four major Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. Roosevelt repeatedly used the term "Four Policemen" starting in 1942.[1]

The Four Policemen would be responsible for keeping order within their spheres of influence: Britain in its empire and Western Europe, the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe and the central Eurasian landmass, China in East Asia and the Western Pacific; and the United States in the Western Hemisphere. As a preventive measure against new wars, countries other than the Four Policemen were to be disarmed. Only the Four Policemen would be allowed to possess any weapons more powerful than a rifle.[2]

Initially, Roosevelt envisioned the new postwar international organization would be formed several years after the war. Later, he came to view creating the United Nations as the most important goal for the entire war effort.[3] His vision for the organization consisted of three branches: an executive branch with the Big Four, an enforcement branch composed of the same four great powers acting as the Four Policemen or Four Sheriffs, and an international assembly representing other nations.[4]

As a compromise with internationalist critics, the Big Four nations became the permanent members of the UN Security Council, with significantly less power than had been envisioned in the Four Policemen proposal.[5] When the United Nations was officially established later in 1945, France was in due course added as the fifth permanent member of the Security Council[6] because of the insistence of Churchill.

History

Background

After World War I, the United States pursued a policy of isolationism and declined to join the League of Nations in 1919. Roosevelt had been a supporter of the League of Nations but, by 1935, he told his foreign policy adviser Sumner Welles: "The League of Nations has become nothing more than a debating society, and a poor one at that!".[7] Roosevelt criticized the League for representing the interests of too many nations. He came to favor an approach to global peace secured through the unified efforts of the world's great powers, rather than through the Wilsonian notions of international consensus and collaboration that guided the League of Nations.[8]

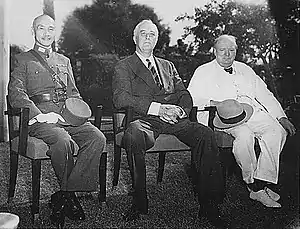

The idea that great powers should "police" the world had been discussed by President Roosevelt as early as August 1941, during his first meeting with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. When the Atlantic Charter was issued, Roosevelt had ensured that the charter omitted mentioning any American commitment towards the establishment of a new international body after the war.[9] He was reluctant to publicly announce his plans for creating a postwar international body, aware of the risk that the American people might reject his proposals, and he did not want to repeat Woodrow Wilson's struggle to convince the Senate to approve American membership in the League of Nations.

Roosevelt's proposal was to create a new international body led by a "trusteeship" of great powers that would oversee smaller countries. In September 1941, he wrote:

In the present complete world confusion, it is not thought advisable at this time to reconstitute a League of Nations which, because of its size, makes for disagreement and inaction... There seem no reason why the principle of trusteeship in private affairs should be not be extended to the international field. Trusteeship is based on the principle of unselfish service. For a time at least there are many minor children among the peoples of the world who need trustees in their relations with other nations and people, just as there are many adult nations or peoples which must be led back into a spirit of good conduct.[8]

Despite a "desultory" first effort, the U.S. State Department's postwar planning had been in abeyance for most of 1940 and 1941.[10] Following the Atlantic Conference, a directive on postwar planning was prepared by the State Department by mid-October, which was delivered to the President in late December.[11]

Plans for the Four Policemen

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 led to a change in Roosevelt's position. He transformed his trusteeship proposal into a proposal for Four Policemen – the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and China – to enforce the peace after the war for several years while other nations, friend and foe, would be disarmed.[8] Roosevelt made his first references to the Four Policemen proposal in early 1942.[12] This would not preclude the eventual formation of a worldwide organisation of nations "for the purpose of full discussion" provided "management" was left to the Four Policemen.[2]

He presented his postwar plans to Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov,[13] who had arrived in Washington on May 29 to discuss the possibility of launching a second front in Europe.[14] The President said to Molotov that "he could not visualize another League of Nations with 100 different signatories; there were simply too many nations to satisfy, hence it was a failure and would be a failure".[15] Roosevelt told Molotov that the Big Four must unite after the war to police the world and disarm aggressor states.[12] When Molotov asked about the role of other countries, Roosevelt answered by opining that too many "policemen" could lead to infighting, but he was open to the idea of allowing other allied countries to participate.[12] A memorandum of the conference summarizes their conversation:

The President told Molotov that he visualized the enforced disarmament of our enemies and, indeed, some of our friends after the war; that he thought that the United States, England, Russia and perhaps China should police the world and enforce disarmament by inspection. The President said that he visualized Germany, Italy, Japan, France, Czechoslovakia, Rumania and other nations would not be permitted to have military forces. He stated that other nations might join the first four mentioned after experience proved they could be trusted.[15]

Roosevelt and Molotov continued their discussion of the Four Policemen in a second meeting on June 1. Molotov informed the President that Stalin was willing to support Roosevelt's plans for maintaining postwar peace through the Four Policemen and enforced disarmament. Roosevelt also raised the issue of postwar decolonization. He suggested that former colonies should undergo a period of transition under the governance of an international trusteeship prior to their independence.[13][16]

China was brought in as a member of the Big Four and a future member of the Four Policemen. Roosevelt was in favor of recognizing China as a great power because he was certain that the Chinese would side with the Americans against the Soviets. He said to British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, "In any serious conflict of policy with Russia, [China] would undoubtedly line up on our side." As it was before the Chinese Civil War ensued, he did not mean the Communist China, but the Republic of China.[17] The President believed that a pro-American China would be useful for the United States should the Americans, Soviets, and Chinese agree to jointly occupy Japan and Korea after the war.[18] When Molotov voiced concerns about the stability of China, Roosevelt responded by saying that the combined "population of our nations and friends was well over a billion people".[15][13]

Churchill objected to Roosevelt's inclusion of China as one of the Big Four because he feared that the Americans were trying to undermine Britain's colonial holdings in Asia. In October 1942, Churchill told Eden that Republican China represented a "faggot vote on the side of the United States in any attempt to liquidate the British overseas empire."[19] Eden shared this view with Churchill and expressed skepticism that China, which was then in the midst of a civil war, could ever return to a stable nation. Roosevelt responded to Churchill's criticism by telling Eden that "China might become a very useful power in the Far East to help police Japan" and that he was fully supportive of offering more aid to China.[18]

Formation of the United Nations

On New Year's Day 1942, the representatives of Allied "Big Four", the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China, signed a short document which later came to be known as the Declaration by United Nations and the next day the representatives of twenty-two other nations added their signatures.[20][21]

President Roosevelt initiated post-war plans for the creation of a new and more durable international organization that would replace the former League of Nations. Roosevelt's Four Policemen proposal received criticism from liberal internationalists who wanted power to be more evenly distributed among nations. Internationalists were concerned that the Four Policemen could lead to a new Quadruple Alliance.[5]

A new plan for the United Nations was drafted by the State Department in April 1944. It kept the emphasis on great power solidarity that was central to Roosevelt's Four Policemen proposal for the United Nations. The members of the Big Four would serve as permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Each of the four permanent members would be given a United Nations Security Council veto power, which would override any UN resolution that went against the interests of one of the Big Four. However, the State Department had compromised with the liberal internationalists. Membership eligibility was widened to include all nation states fighting against the Axis powers instead of a select few.

Roosevelt had been a supporter of the League of Nations back in 1919–20, but was determined to avoid the mistakes Woodrow Wilson had made. The United Nations was FDR's highest postwar priority. He insisted on full coordination with the Republican leadership. He made sure that leading Republicans were on board, especially Senators Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan,[22] and Warren Austin of Vermont.[23] In a broad sense, Roosevelt believed that the UN could solve the minor problems and provide the chief mechanism to resolve any major issues that arose among the great powers, all of whom would have a veto. Roosevelt was especially interested in international protection of human rights, and in this area his wife played a major role as well.[24][25]

The Dumbarton Oaks Conference convened in August 1944 to discuss plans for the postwar United Nations with delegations from the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China.[5] US President Franklin D. Roosevelt considered his most important legacy the creation of the United Nations, making a permanent organization out of the wartime Alliance of the same name. He was the chief promoter of the United Nations idea.

The Big Four were the only four sponsoring countries of the San Francisco Conference of 1945 and their heads of the delegations took turns as chairman of the plenary meetings.[26] During this conference, the Big Four and their allies signed the Charter of the United Nations.[27]

Legacy

In the words of a former Undersecretary General of the UN, Sir Brian Urquhart:

It was a pragmatic system based on the primacy of the strong – a "trusteeship of the powerful", as he then called it, or, as he put it later, "the Four Policemen". The concept was, as [Senator Arthur H.] Vandenberg noted in his diary in April 1944, "anything but a wild-eyed internationalist dream of a world state.... It is based virtually on a four-power alliance." Eventually this proved to be both the potential strength and the actual weakness of the future UN, an organization theoretically based on a concert of great powers whose own mutual hostility, as it turned out, was itself the greatest potential threat to world peace.[28]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Richard W. Van Alstyne, "The United States and Russia in World War II: Part I" Current History 19#111 (1950), pp. 257-260 online

- 1 2 Gaddis 1972, p. 25.

- ↑ For Roosevelt, "establishing the United nations organization was the overarching strategic goal, the absolute first priority." Townsend Hoopes; Douglas Brinkley (1997). FDR and the Creation of the U.N. Yale UP. p. 178. ISBN 0300085532.

- ↑ Hoopes & Brinkley 1997, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 Gaddis 1972, p. 27.

- ↑ 1946-47 Part 1: The United Nations. Section 1: Origin and Evolution.Chapter E: The Dumbarton Oaks Conversations. The Yearbook of the United Nations. United Nations. p. 6. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ↑ Welles 1951, pp. 182–204.

- 1 2 3 Gaddis 1972, p. 24.

- ↑ Gaddis 1972, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Hoopes & Brinkley 1997, pp. 43–45.

- ↑ Hoopes & Brinkley 1997, pp. 45.

- 1 2 3 Kimball 1991, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 Dallek 1995, p. 342.

- ↑ Gaddis 1972, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 United States Department of State 1942, p. 573.

- ↑ United States Department of State 1942, p. 580.

- ↑ Westad, Odd (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8047-4484-3.

- 1 2 Dallek 1995, p. 390.

- ↑ Dallek 1995, p. 389.

- ↑ United Nations Official Website 1942.

- ↑ Ma 2003, pp. 203–204.

- ↑ James A. Gazell, "Arthur H. Vandenberg, Internationalism, and the United Nations." Political Science Quarterly 88#3 (1973): 375-394. online

- ↑ George T. Mazuzan. Warren R. Austin at the U. N., 1946-1953 (Kent State UP, 1977).

- ↑ Ivy P. Urdang, "Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: Human Rights and the Creation of the United Nations." OAH Magazine of History 22.2 (2008): 28-31.

- ↑ M. Glen Johnson, "The contributions of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt to the development of international protection for human rights." Human Rights Quarterly 9 (1987): 19+.

- ↑ United Nations Official Website 1945.

- ↑ Gaddis 1972, p. 28.

- ↑ Urquhart 1998.

Sources

- Bosco, David (2009). Five to Rule Them All: The UN Security Council and the Making of the Modern World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532876-9.

- Dallek, Robert (1995). Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945: With a New Afterword. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-982666-7.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (1972). The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12239-9.

- Hoopes, Townsend; Brinkley, Douglas (1997). FDR and the Creation of the U.N.. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08553-2.

- Kimball, Warren F. (1991). The Juggler: Franklin Roosevelt as Wartime Statesman. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03730-2.

- Ma, Xiaohua (2003). The Sino-American alliance during World War II and the lifting of the Chinese exclusion acts. New York: Routledge. pp. 203–204. ISBN 0-415-94028-1.

- United States Department of State (1942). "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics". Foreign relations of the United States diplomatic papers, 1942. Europe Volume III. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 406–771.

- Welles, Sumner (January 1951). "Two Roosevelt Decisions: One Debit, One Credit". Foreign Affairs. Vol. 29, no. 2. pp. 182–204.

- Online

- "1942: Declaration of The United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- "1945: The San Francisco Conference". United Nations. 1945. Archived from the original on Oct 30, 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Urquhart, Brian (16 July 1998). "Looking for the Sheriff". New York Review of Books.

External links

- "Instrumental Internationalism: The American Origins of the United Nations, 1940–3" by Stephen Wertheim

- "US: UN" by Peter Gowan