| Commonwealth Games |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Main topics |

| Games |

| Commonwealth Games | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sports (details) | |

The Commonwealth Games[lower-alpha 1] is a quadrennial international multi-sport event among athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations, which mostly consists of territories of the former British Empire. The event was first held in 1930 and, with the exception of 1942 and 1946 (cancelled due to World War II), has successively run every four years since.[5] The event was called the British Empire Games from 1930 to 1950, the British Empire and Commonwealth Games from 1954 to 1966, and British Commonwealth Games from 1970 to 1974. Athletes with a disability are included as full members of their national teams since 2002, making the Commonwealth Games the first fully inclusive international multi-sport event.[6] In 2018, the Games became the first global multi-sport event to feature an equal number of men's and women's medal events, and four years later they became the first global multi-sport event to have more events for women than men.[7]

Inspired by the Inter-Empire Championships, part of the 1911 Festival of Empire, Melville Marks Robinson founded the British Empire Games which was first held in Hamilton, Canada in 1930.[8] As time progressed, the Games evolved, adding the Commonwealth Paraplegic Games for athletes with a disability (who were barred from competing from 1974 before being fully integrated by 1990)[9] and the Commonwealth Youth Games for athletes aged 14 to 18.

The event is overseen by the Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF), which controls the sporting programme and selects host cities. The games movement consists of international sports federations (IFs), Commonwealth Games Associations (CGAs) and organising committees for each specific Commonwealth Games. Certain traditions, such as the hoisting of the Commonwealth Games flag and Queen's Baton Relay, as well as the opening and closing ceremonies, are unique to the Games. Over 4,500 athletes competed at the latest Commonwealth Games in 25 sports and over 250 medal events, including Olympic and Paralympic sports and those popular in Commonwealth countries: bowls and squash.[10] Usually, the first, second and third-place finishers in each event are awarded gold, silver and bronze medals, respectively.

One of the differences from other multisport events is that fifteen CGAs participating in the Commonwealth Games do not send their delegations independently from the Olympic, Paralympic and other multisports competitions, as thirteen are linked to the British Olympic Association, one is part of the Australian Olympic Committee and another is part of the New Zealand Olympic Committee. They are the four Home Nations of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), the British Overseas Territories (Anguilla, Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Montserrat, Saint Helena and Turks and Caicos Islands), the Crown Dependencies (Guernsey, Isle of Man, and Jersey), along with the Australian territory of Norfolk Island and the New Zealand associated state of Niue.[11]

Twenty cities in nine countries (counting England, Scotland and Wales separately) have hosted the games. Australia has hosted the Commonwealth Games five times (1938, 1962, 1982, 2006 and 2018), more than any other nation. Two cities have hosted Commonwealth Games more than once: Auckland (1950, 1990) and Edinburgh (1970, 1986).[12] The most recent Commonwealth Games, the 22nd, was held in Birmingham from 28 July to 8 August 2022. The withdrawal of numerous host cities for the 2026 Commonwealth Games has led to speculation that those of 2022 may have been the last.[13]

History

A sporting competition bringing together the members of the British Empire was first proposed by John Astley Cooper in 1891, who wrote letters and articles for several periodicals suggesting a "Pan Brittanic, Pan Anglican Contest every four years as a means of increasing goodwill and understanding of the British Empire."[14] John Astley Cooper Committees were formed in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa to promote the idea and inspired Pierre de Coubertin to start the international Olympic Games movement.[15][16]

In 1911, an Inter-Empire Championship was held alongside the Festival of Empire, at The Crystal Palace in London to celebrate the coronation of George V, and were championed by The Earl of Plymouth and Lord Desborough.[17][18] Teams from Australasia (Australia and New Zealand), Canada, South Africa, and the United Kingdom competed in events for athletics, boxing, swimming and wrestling.[19] Canada won the championships and was presented with a silver cup (gifted by Lord Lonsdale) which was 2 feet 6 inches (76 cm) high and weighed 340 ounces (9.6 kg). A correspondent of the Auckland Star criticised the Games, calling them a "grievous disappointment" that were "not worthy of the title of 'Empire Sports'".[20]

While planning for the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam, Amateur Athletic Union of Canada executive J. Howard Crocker spoke with journalist Melville Marks Robinson of The Hamilton Spectator, about hosting an international sporting event in Canada. Robinson proposed and lobbied to host what became the British Empire Games in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1930.[21][22] Robinson then served as the manager of the Canadian track and field team for the 1930 British Empire Games.[22]

Although there are 56 members of the Commonwealth of Nations, there are 72 Commonwealth Games Associations. They are divided into six regions (Africa, Americas, Caribbean, Europe, Asia and Oceania) and each has a similar function to the National Olympic Committees in relation with their countries or territories. In some, like India and South Africa, the CGA functions are assumed by their NOCs.

Only six nations have participated in every Commonwealth Games: Australia, Canada, England, New Zealand, Scotland and Wales. Of these six, Australia, England, Canada and New Zealand have each won at least one gold medal in every Games. Australia has been the highest-achieving team for thirteen editions of the Games, England for seven and Canada for one. These three teams also top the all-time Commonwealth Games medal table in that order.

Editions

British Empire Games

The 1930 British Empire Games was the first of what later became known as the Commonwealth Games, and was held in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada from 16 to 23 August 1930 and opened by Lord Willingdon.[23] Eleven countries: Australia, Bermuda, British Guyana, Canada, England, Northern Ireland, Newfoundland, New Zealand, Scotland, South Africa and Wales, sent a total of 400 athletes to compete in athletics, boxing, lawn bowls, rowing, swimming and diving and wrestling. The opening and closing ceremonies as well as athletics took place at Civic Stadium.[24] The cost of the Games were $97,973.[24] Women competed in only the aquatic events.[25] Canadian triple jumper Gordon Smallacombe won the first ever gold medal in the history of the Games.[8]

The 1934 British Empire Games was the second of what is now known as the Commonwealth Games, held in London, England. The host city was London, with the main venue at Wembley Park, although the track cycling events were in Manchester. The 1934 Games had originally been awarded to Johannesburg, but was given to London instead because of serious concerns about prejudice against Asian and black athletes in South Africa. The affiliation of Irish athletes at the 1934 Games representation remains unclear but there was no official Irish Free State team. Sixteen national teams took part, including new participants Hong Kong, India, Jamaica, Southern Rhodesia and Trinidad and Tobago.[26]

The 1938 British Empire Games was the third British Empire Games, which was held in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It was timed to coincide with Sydney's sesqui-centenary (150 years since the foundation of British settlement in Australia). Held in the Southern Hemisphere for the first time, the III Games opening ceremony took place at the famed Sydney Cricket Ground in front of 40,000 spectators. Fifteen nations participated down under at the Sydney Games involving a total of 464 athletes and 43 officials. Fiji and Ceylon made their debuts. Seven sports were featured in the Sydney Games – athletics, boxing, cycling, lawn bowls, rowing, swimming and diving and wrestling.[27]

The 1950 British Empire Games was the fourth edition and was held in Auckland, New Zealand after a twelve-year gap from the third edition of the games. The fourth games was originally awarded to Montreal, Canada and was to be held in 1942, but was cancelled due to the Second World War. The opening ceremony at Eden Park was attended by 40,000 spectators, while nearly 250,000 people attended the Auckland Games. Twelve countries sent a total of 590 athletes to Auckland. Malaya and Nigeria made their first appearances.[28]

British Empire and Commonwealth Games

The fifth edition of the Games, the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games, was held in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. This was the first event since the name change from British Empire Games took effect in 1952, the same year of Queen Elizabeth II's reign. The fifth edition of the Games placed Vancouver on a world stage and featured memorable sporting moments as well as outstanding entertainment, technical innovation and cultural events. The 'Miracle Mile', as it became known, saw both the gold medallist, Roger Bannister of England and silver medallist John Landy of Australia, run sub-four-minute races in an event that was televised live across the world for the first time. Northern Rhodesia and Pakistan made their debuts and both performed well, winning eight and six medals respectively.[29]

The 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games was held in Cardiff, Wales. The sixth edition of the games marked the largest sporting event ever held in Wales and it was the smallest country ever to host a British Empire and Commonwealth Games. Cardiff had to wait twelve years longer than originally scheduled to become host of the Games, as the 1946 event was cancelled because of the Second World War. The Cardiff Games introduced the Queen's Baton Relay, which has been conducted as a prelude to every British Empire and Commonwealth Games ever since. Thirty-five nations sent a total of 1,122 athletes and 228 officials to the Cardiff Games and 23 countries and dependencies won medals, including for the first time, Singapore, Ghana, Kenya and the Isle of Man.[30] In the run up to the Cardiff games, many leading sports stars including Stanley Matthews, Jimmy Hill and Don Revie were signatories in a letter to The Times on 17 July 1958 deploring the presence of white-only South African sports, opposing 'the policy of apartheid' in international sport and defending 'the principle of racial equality which is embodied in the Declaration of the Olympic Games'.[31]

The 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games was held in Perth, Western Australia. Thirty-five countries sent a total of 863 athletes and 178 officials to Perth. Jersey was among the medal winners for the first time, while British Honduras, Dominica, Papua and New Guinea and St Lucia all made their inaugural Games appearances. Aden also competed by special invitation. Sarawak, North Borneo and Malaya competed for the last time, before taking part in 1966 under the Malaysian flag. In addition, Rhodesia and Nyasaland competed in the Games as an entity for the first and only time.[32]

The 1966 British Empire and Commonwealth Games was held in Kingston, Jamaica. This was the first time that the Games had been held outside the so-called White Dominions. Thirty-four nations (including South Arabia) competed in the Kingston Games, sending a total of 1,316 athletes and officials.[33]

British Commonwealth Games

The 1970 British Commonwealth Games was held in Edinburgh, Scotland. This was the first time the name British Commonwealth Games was adopted, the first time metric units rather than imperial units were used in events, the first time the games were held in Scotland and also the first time that HM Queen Elizabeth II attended in her capacity as Head of the Commonwealth.[34]

The 1974 British Commonwealth Games was held in Christchurch, New Zealand. The event was officially named The Friendly Games, and was also the first edition to feature a theme song. Following the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics, the tenth games at Christchurch were the first multi-sport event to place the safety of participants and spectators as its uppermost requirement. Security guards surrounded the athlete's village and there was an exceptionally high-profile police presence. Only 22 countries succeeded in winning medals from the total haul of 374 medals on offer, but first time winners included Western Samoa, Lesotho and Swaziland (since 2018 named Eswatini).[35] The theme song for the 1974 British Commonwealth Games was called "Join Together".

Commonwealth Games

The 1978 Commonwealth Games was held in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. This event was the first to bear the current day name of the Commonwealth Games, and also marked a new high as almost 1,500 athletes from 46 countries took part. They were boycotted by Nigeria in protest against New Zealand's sporting contacts with apartheid-era South Africa, as well as by Uganda in protest at alleged Canadian hostilities toward the government of Idi Amin.[36][37]

The 1982 Commonwealth Games was held in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Forty-six nations participated in the Brisbane Games with a new record total of 1,583 athletes and 571 officials. As hosts, Australia headed the medal table leading the way ahead of England, Canada, Scotland and New Zealand respectively. Zimbabwe made its first appearance at the Games, having earlier competed as Southern Rhodesia and as part of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.[38] The theme song for the 1982 Commonwealth Games was called "You're Here To Win".

The 1986 Commonwealth Games was held in Edinburgh, Scotland and were the second Games to be held in Edinburgh. Participation at the 1986 Games was affected by a boycott by 32 African, Asian and Caribbean nations in protest at British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's refusal to condemn sporting contacts of apartheid era South Africa in 1985, but the Games rebounded and continued to grow thereafter. Twenty-six nations did attend the second Edinburgh Games, and sent a total of 1,662 athletes and 461 officials.[39] The theme song for the 1986 Commonwealth Games was called "Spirit Of Youth".

The 1990 Commonwealth Games was held in Auckland, New Zealand. It was the fourteenth Commonwealth Games, the third to be hosted by New Zealand and Auckland's second. A new record of 55 nations participated in the second Auckland Games, sending 2,826 athletes and officials.[40] Pakistan returned to the Commonwealth in 1989 after withdrawing in 1972, and competed in the 1990 Games after an absence of twenty years.[41] The theme song for the 1990 Commonwealth Games was called "This Is The Moment".

The 1994 Commonwealth Games was held in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. This event was the fourth to take place in Canada. The games marked another point of South Africa's return to the sporting atmosphere following the apartheid era, and over thirty years since the country last competed in the Games in 1958.A former south african territory Namibia made its Commonwealth Games debut. It was also Hong Kong's last appearance at the games before the transfer of sovereignty from Britain to China. Sixty-three nations sent 2,557 athletes and 914 officials.[42] The theme song for the 1994 Commonwealth Games was called "Let Your Spirit Take Flight".

The 1998 Commonwealth Games was held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. For the first time in its 68-year history, the Commonwealth Games was held in Asia. The event was also the first Games to feature team sports (cricket,rugby 7's,netball and field hockey) along ten pin bowling and squash– an overwhelming success that added large numbers to both participant and TV audience numbers. A new record of 70 countries sent a total of 5,065 athletes and officials to the Kuala Lumpur Games. The top five countries in the medal standing were Australia, England, Canada, Malaysia (who made their best games' performance until that date) and South Africa. Nauru also achieved an impressive haul of three gold medals. Cameroon, Mozambique, Kiribati and Tuvalu debuted.[43] The theme song for the 1998 Commonwealth Games was called "Forever As One".

During the 21st century

The 2002 Commonwealth Games was held in Manchester, England. The event was hosted in England for the first time since 1934 and hosted to coincide with the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II, head of the Commonwealth. In terms of sports and events, the 2002 event was until the 2010 edition the largest Commonwealth Games in history featuring 281 events across 17 sports. The final medal tally was led by Australia, followed by host England and Canada. The 2002 Commonwealth Games had set a new benchmark for hosting the Commonwealth Games and for cities wishing to bid for them with a heavy emphasis on legacy.[44] The theme song for the 2002 Commonwealth Games was called "Where My Heart Will Take Me".

The 2006 Commonwealth Games was held in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The only difference between the 2006 games and the 2002 games was the absence of Zimbabwe, which withdrew from the Commonwealth of Nations. For the first time in the history of the Games the Queen's Baton visited every single Commonwealth nation and territory taking part in the Games, a journey of 180,000 kilometres (110,000 mi). Over 4000 athletes took part in the sporting competitions. Again the Top 3 on the medal table is Australia, followed by England and Canada.[45] The theme song for the 2006 Commonwealth Games was called "Together We Are One".

The 2010 Commonwealth Games was held in Delhi, India. The Games cost $11 billion and is the most expensive Commonwealth Games ever. It was the first time that the Commonwealth Games was held in India, also the first time that a Commonwealth republic hosted the games and the second time it was held in Asia after Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 1998. A total of 6,081 athletes from 71 Commonwealth nations and dependencies competed in 21 sports and 272 events. The final medal tally was led by Australia. The host nation India achieved its best performance ever in any sporting event, finishing second overall.[46] Rwanda made its Games debut.[47] The theme song for the 2010 Commonwealth Games was called "Live, Rise, Ascend, Win".

The 2014 Commonwealth Games was held in Glasgow, Scotland. It was the largest multi-sport event ever held in Scotland with around 4,950 athletes from 71 different nations and territories competing in 18 different sports, outranking the 1970 and 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, capital city of Scotland. Usain Bolt competed in the 4×100 metres relay of the 2014 Commonwealth Games and set a Commonwealth Games record with his teammates.[48] The Games received acclaim for their organisation, attendance, and the public enthusiasm of the people of Scotland, with the CGF chief executive Mike Hooper hailing them as "the standout games in the history of the movement".[49]

The 2018 Commonwealth Games was held in Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, the fifth time Australia hosted the Games. There were an equal number of events for men and women, the first time in history that a major multi-sport event had equality in terms of events.[50][51]

The 2022 Commonwealth Games was held in Birmingham, England. It was the third Commonwealth Games to be hosted in England, following London 1934 and Manchester 2002.[52] The 2022 Commonwealth Games coincided with the Platinum Jubilee of Elizabeth II and the tenth anniversary of the 2012 Summer Olympics and the 2012 Summer Paralympics, both staged in London. The 2022 Commonwealth Games was the last edition to be held under Queen Elizabeth II, before her death on 8 September 2022.

On 16 February 2022, it was announced that the 2026 Commonwealth Games would be held for a record sixth time in Australia, but for the first time they would be decentralised, as the state of Victoria signed as host 'city'. The event were to have four regional clusters mainly focused in Bendigo region, and another three regional centres. The 2026 Commonwealth Games were to be the first games to be held under the reign of King Charles III. It was also confirmed that the Commonwealth Games, scheduled for 2030 were likely to be awarded to Hamilton, Canada.[53] However, in July 2023, the Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews announced that Victoria would no longer host the 2026 Games,[54] with Alberta, pulling out of their part in a joint Canadian bid for the 2030 edition of the Games shortly after.[55]

Many commentators are now questioning the continuing viability of the Commonwealth Games.[56] The three nations to have hosted the Commonwealth Games the most times are Australia (5), Canada (4) and New Zealand (3). With the 2022 games, England increased its number to three. Six Games have taken place in the countries within the United Kingdom (Scotland (3) and Wales (1)), two in Asia (Malaysia (1) and India (1)) and one in the Caribbean (Jamaica (1)).[5]

Paraplegic Games

The Commonwealth Paraplegic Games were an international, multi-sport event involving athletes with a disability from the Commonwealth countries. The event was sometimes referred to as the Paraplegic Empire Games and British Commonwealth Paraplegic Games. Athletes were generally those with spinal injuries or polio. The event was first held in 1962 and disestablished in 1974.[57] The Games were held in the country hosting the Commonwealth Games for able-bodied athletes. The countries that had hosted the Commonwealth Paraplegic Games were Australia, Jamaica, Scotland and New Zealand in 1962, 1966, 1970 and 1974. Six countries – Australia, England, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales — had been represented at all Commonwealth Paraplegic Games. Australia and England had been the top-ranking nation two times each: 1962, 1974 and 1966, 1970.

Inclusion of disabled athletes

Athletes with a disability were then first included the 1994 Commonwealth Games in Victoria, British Columbia when this events was added to athletics and lawn bowls,[58] As at 2002 Commonwealth Games in Manchester, England, they were included as compulsory events, making them the first fully inclusive international multi-sport games. This meant that results were included in the medal count and the athletes are full members of each country delegation.[59]

During the 2007 General Assembly of the Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) at Colombo, Sri Lanka, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) and CGF signed a co-operative agreement to ensure a formal institutional relationship between the two bodies and secure the future participation of elite athletes with a disability (EAD) in future Commonwealth Games.

Then, IPC President Philip Craven said during the General Assembly:

"We look forward to working with CGF to develop the possibilities of athletes with a disability at the Commonwealth Games and within the Commonwealth. This partnership will help to galvanize Paralympic sports development in Commonwealth countries/territories and seek to create and promote greater opportunities in sport for athletes with a disability".

— IPC President Sir Philip Craven

The co-operation agreement outlined the strong partnership between the IPC and the CGF. It recognised the IPC as the respective sport body and have the function to oversee the co-ordination and delivery of the Commonwealth Games EAD sports programme and committed both organisations to work together in supporting the growth of the Paralympic and Commonwealth Games Movements.[60]

Winter Games

The Commonwealth Winter Games was a multi-sport event comprising winter sports, last held in 1966. Three editions of the Games have been staged. The Winter Games were designed as a counterbalance to the Commonwealth Games, which focuses on summer sports, to accompany the Winter Olympics and Summer Olympic Games. The winter Games were founded by T.D. Richardson.[61] The 1958 Commonwealth Winter Games were held in St. Moritz, Switzerland and was the inaugural games for the winter edition.[62][63] The 1962 Games were also held in St. Moritz, complementing the 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Perth, Australia, and the 1966 event was held in St. Moritz as well, following which the idea was discontinued.[64]

Youth Games

The Commonwealth Youth Games is an international multi-sport event organised by the Commonwealth Games Federation. The Games are held every four years with the current Commonwealth Games format. The Commonwealth Games Federation discussed the idea of a Millennium Commonwealth Youth Games in 1997. In 1998, the concept was agreed on for the purpose of providing a Commonwealth multi-sport event for young people born in the calendar year 1986 or later. The first version was held in Edinburgh, Scotland from 10 to 14 August 2000. The age limitation of the athletes is 14 to 18.[65]

Commonwealth Games Federation

_(2).jpg.webp)

The Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) is the international organisation responsible for the direction and control of the Commonwealth Games and Commonwealth Youth Games, and is the foremost authority in matters relating to the games.[66] The Commonwealth House in London, England hosts the headquarters of CGF.[67] The Commonwealth House also hosts the headquarters of the Royal Commonwealth Society and the Commonwealth Local Government Forum.[68][69]

The Commonwealth Games Movement is made of three major elements:

- International Federations (IFs) are the governing bodies that supervise a sport at an international level. For example, the International Basketball Federation (FIBA) is the international governing body for basketball.[70]

- Commonwealth Games Associations (CGAs) represent and regulate the Commonwealth Games Movement within each country and perform similar functions as the National Olympic Committees. For example, the Commonwealth Games England (CGE) is the CGA of England. There are currently 72 CGAs recognised by the CGF.[71]

- Organising Committees for the Commonwealth Games (OCCWGs) are temporary committees responsible for the organisation of each Commonwealth Games. OCCWGs are dissolved after each Games once the final report is delivered to the CGF.

English is the official language of the Commonwealth. The other language used at each Commonwealth Games is the language of the host country (or languages, if a country has more than one official language apart from English). Every proclamation (such as the announcement of each country during the parade of nations in the opening ceremony) is spoken in these two (or more) languages. If the host country does this, it is their responsibility to choose the language{s) and their order.[72]

Queen's Baton Relay

The Queen's Baton Relay is a relay around the world held prior to the beginning of the Commonwealth Games. The Baton carries a message from the Head of the Commonwealth. The Relay traditionally begins at Buckingham Palace in London as a part of the city's Commonwealth Day festivities. The Queen entrusts the baton to the first relay runner. At the Opening Ceremony of the Games, the final relay runner hands the baton back to the Queen or his representative, who reads the message aloud to officially open the Games. The Queen's Baton Relay is similar to the Olympic Torch Relay.[73]

The Relay was introduced at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, Wales as the Queen's Baton Relay. Up until, and including, the 1994 Commonwealth Games, the Relay only went through England and the host nation. The Relay for the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia was the first to travel to other nations of the Commonwealth.

The Queen's Baton Relay for the 2018 Commonwealth Games held on the Gold Coast, Australia, was the longest in Commonwealth Games history. Covering 230,000 km (150,000 miles) over 388 days, the Baton made its way through the six Commonwealth regions of Africa, the Americas, the Caribbean, Europe, Asia and Oceania. For the first time, the Queen's Baton was presented at the Commonwealth Youth Games during its sixth edition in 2017, which were held in Nassau, Bahamas.[74]

Ceremonies

Opening

Various elements frame the opening ceremony of the Commonwealth Games. This ceremony takes place before the events have occurred. The ceremony typically starts with the hoisting of the host country's flag and a performance of its national anthem. The flag of the Commonwealth Games Federation, flag of the last hosting nation and the next hosting nation are also hosted during the opening ceremony. The host nation then presents artistic displays of music, singing, dance and theatre representative of its culture. The artistic presentations have grown in scale and complexity as successive hosts attempt to provide a ceremony that outlasts its predecessor's in terms of memorability. The opening ceremony of the Delhi Games reportedly cost $70 million, with much of the cost incurred in the artistic segment.[75]

After the artistic portion of the ceremony, the athletes parade into the stadium grouped by nation. The last hosting nation is traditionally the first nation to enter. Nations then enter the stadium alphabetical or continental wise with the host country's athletes being the last to enter. Speeches are given, formally opening the Games. Finally, the King's Baton is brought into the stadium and passed on until it reaches the final baton carrier, often a successful Commonwealth athlete from the host nation, who hands it over to the Head of the Commonwealth or his representative.

Closing

The closing ceremony of the Commonwealth Games takes place after all sporting events have concluded. Flag-bearers from each participating country enter the stadium, followed by the athletes who enter together, without any national distinction. The president of the organising committee and the CGF president make their closing speeches and the Games are officially closed. The CGF president also speaks about the conduct of the games. The mayor of the city that organised the Games transfers the CGF flag to the president of the CGF, who then passes it on to the mayor of the city hosting the next Commonwealth Games. The next host nation then also briefly introduces itself with artistic displays of dance and theatre representative of its culture. Many great artists and singers had performed at the ceremonies of the Commonwealth Games.[76]

At the closing ceremony of every Commonwealth Games, the CGF President makes an award and presents a trophy to one athlete who has competed with particular distinction and honour both in terms of athletic performance and overall contribution to his or her team. Athletes are nominated by their Commonwealth Games Association at the end of the final day of competition and the winner is selected by a panel comprising the CGF President and representatives from each of the six Commonwealth Regions. The ‘David Dixon Award’ as it is called was introduced in Manchester 2002, after the late David Dixon, former Honorary Secretary of the CGF, in honour of his monumental contribution to Commonwealth sport for many years.[77]

Medal presentation

A medal ceremony is held after each event is concluded. The winner, second and third-place competitors or teams stand on top of a three-tiered rostrum to be awarded their respective medals. After the medals are given out by a CGF member, the national flags of the three medallists are raised while the national anthem of the gold medallist's country plays. Volunteering citizens of the host country also act as hosts during the medal ceremonies, as they aid the officials who present the medals and act as flag-bearers.

Anthems

"God Save the King" is an official or national anthem of multiple Commonwealth countries. As a result, and due to the countries of the United Kingdom competing individually, it is not played in some official events, medal ceremonies or before matches in team events.[78]

Anthems used at the Commonwealth Games which differ from a currently-eligible country's national or official anthem(s):

| Country | Victory Anthem used at the Commonwealth Games | National Anthem(s)/Official Anthem(s) |

|---|---|---|

| "God Bless Anguilla" | "God Save the King" | |

| "Hail to Bermuda" | ||

| "Oh, Beautiful Virgin Islands" | ||

| "Beloved Isle Cayman" | ||

| "Land of Hope and Glory" (until 2010) "Jerusalem" (since 2010)[79] |

None; "God Save the King" as part of the United Kingdom | |

| "Song of the Falklands" | "God Save the King" | |

| "Gibraltar Anthem" | ||

| "Sarnia Cherie" | ||

| "Island Home" | ||

| "Motherland" | ||

| "God Defend New Zealand" | "God Defend New Zealand" (since 1976)[80] "God Save the King" | |

| "Ko e Iki he Lagi (Lord in Heaven, Thou art merciful)" | "God Defend New Zealand" (since 1976)[80] "God Save the King" | |

| "Come Ye Blessed" | "Advance Australia Fair" | |

| "Londonderry Air" | None; "God Save the King" as part of the United Kingdom | |

| "My Saint Helena Island" | "God Save the King" | |

| "Scotland the Brave" (until 2010) "Flower of Scotland" (since 2010)[81] |

None; "God Save the King" as part of the United Kingdom | |

| "This Land of Ours" | "God Save the King" | |

| "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau (Land of my Fathers)" | "God Save the King" as part of the United Kingdom/ "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau (Land of my Fathers)" |

List of Commonwealth Games

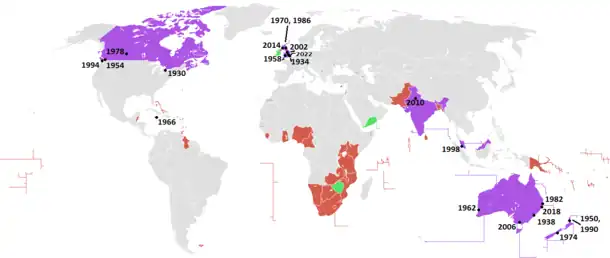

1930 1954 1966 1978 1994 Host cities of Commonwealth Games (Canada and Caribbean) |

1934 1958 1970, 1986 2002 2014 2022 Host cities of Commonwealth Games (Great Britain) |

1938 1950, 1990 1962 1974 1982 2006 2018 Host cities of Commonwealth Games (Australia and New Zealand and Oceania)  2010 1998 Host cities of Commonwealth Games (Asia) |

|

| Year | Edition | Host city | Host Association | Opened by | Sports | Events | Teams | Start date | End date | Competitors | Top Association | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Empire Championships | ||||||||||||

| 1911 | – | London | George V | 4 | 9 | 4 | 12 May | 1 June | Unknown | |||

Note The 1911 Inter-Empire Championships held in London (as part of a festival to celebrate the coronation of King George V) is seen as a precursor to the modern Commonwealth Games, but is not normally considered an official edition of the Games themselves. Also, the United Kingdom competed as one country, unlike the Commonwealth Games today when they compete as England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Canada topped the medal table by winning 4 events.[82]

Editions

| Year | Edition | Host city | Host Association | Opened by | Sports | Events | Associations | Start date | End date | Competitors | Top Association | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | I | Hamilton | Viscount Willingdon | 6 | 59 | 11 | 16 Aug | 23 Aug | 400 | |||

| 1934 | II | London | King George V | 6 | 68 | 16 | 4 Aug | 11 Aug | 500 | |||

| 1938 | III | Sydney | Lord Wakehurst | 7 | 71 | 15 | 5 Feb | 12 Feb | 464 | |||

| 1942 | – | Montreal | Cancelled due to World War II[83] | |||||||||

| 1946 | – | Cardiff | ||||||||||

| 1950 | IV | Auckland | Sir Bernard Freyberg | 9 | 88 | 12 | 4 Feb | 11 Feb | 590 | |||

| 1954 | V | Vancouver | Earl Alexander of Tunis | 9 | 91 | 24 | 30 Jul | 7 Aug | 662 | |||

| 1958 | VI | Cardiff | Philip, Duke of Edinburgh | 9 | 94 | 36 | 18 Jul | 26 Jul | 1122 | |||

| 1962 | VII | Perth | 9 | 104 | 35 | 22 Nov | 1 Dec | 863 | ||||

| 1966 | VIII | Kingston | 9 | 110 | 34 | 4 Aug | 13 Aug | 1050 | ||||

| 1970 | IX | Edinburgh | 9 | 121 | 42 | 16 Jul | 25 Jul | 1383 | ||||

| 1974 | X | Christchurch | 9 | 121 | 38 | 24 Jan | 2 Feb | 1276 | ||||

| 1978 | XI | Edmonton | Queen Elizabeth II | 10 | 128 | 46 | 3 Aug | 12 Aug | 1474 | |||

| 1982 | XII | Brisbane | Philip, Duke of Edinburgh | 10 | 142 | 46 | 30 Sep | 9 Oct | 1583 | |||

| 1986 | XIII | Edinburgh | Queen Elizabeth II | 10 | 163 | 26 | 24 Jul | 2 Aug | 1662 | |||

| 1990 | XIV | Auckland | Prince Edward | 10 | 204 | 55 | 24 Jan | 3 Feb | 2073 | |||

| 1994 | XV | Victoria | Queen Elizabeth II | 10 | 217 | 63 | 18 Aug | 28 Aug | 2557 | |||

| 1998 | XVI | Kuala Lumpur | Tuanku Jaafar | 15 | 213 | 70 | 11 Sep | 21 Sep | 3633 | |||

| 2002 | XVII | Manchester | Queen Elizabeth II | 17 | 281 | 72 | 25 Jul | 4 Aug | 3679 | |||

| 2006 | XVIII | Melbourne | 16 | 245 | 71 | 15 Mar | 26 Mar | 4049 | ||||

| 2010 | XIX | Delhi | Pratibha Patil Charles, Prince of Wales |

17 | 272 | 71 | 3 Oct | 14 Oct | 4352 | |||

| 2014 | XX | Glasgow | Queen Elizabeth II | 17 | 261 | 71 | 23 Jul | 3 Aug | 4947 | |||

| 2018 | XXI | Gold Coast | Charles, Prince of Wales | 19 | 275 | 71 | 4 Apr | 15 Apr | 4426 | |||

| 2022 | XXII | Birmingham | 20 | 280 | 72 | 28 Jul | 8 Aug | 5054 | [84] | |||

| 2026 | XXIII | TBD[85] | TBD | King Charles III (expected) | TBD | |||||||

Medal table

*Note : Nations in italics no longer participate at the Commonwealth Games.

- Updated after 2022 Commonwealth Games.

| Rank | CGA | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1003 | 834 | 767 | 2604 | |

| 2 | 773 | 783 | 766 | 2322 | |

| 3 | 510 | 548 | 589 | 1647 | |

| 4 | 203 | 190 | 171 | 564 | |

| 5 | 179 | 232 | 295 | 706 | |

| 6 | 137 | 132 | 147 | 416 | |

| 7 | 132 | 143 | 227 | 502 | |

| 8 | 91 | 80 | 87 | 258 | |

| 9 | 82 | 84 | 105 | 271 | |

| 10 | 75 | 104 | 155 | 334 | |

| 11 | 69 | 78 | 91 | 238 | |

| 12 | 65 | 53 | 58 | 176 | |

| 13 | 41 | 31 | 37 | 109 | |

| 14 | 37 | 46 | 59 | 142 | |

| 15 | 27 | 27 | 29 | 83 | |

| 16 | 25 | 16 | 23 | 64 | |

| 17 | 19 | 16 | 25 | 60 | |

| 18 | 15 | 20 | 28 | 63 | |

| 19 | 13 | 23 | 26 | 62 | |

| 20 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 38 | |

| 21 | 11 | 12 | 17 | 40 | |

| 22 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 31 | |

| 23 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 29 | |

| 24 | 6 | 9 | 14 | 29 | |

| 25 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 24 | |

| 26 | 5 | 13 | 24 | 42 | |

| 27 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 15 | |

| 28 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 19 | |

| 29 | 5 | 4 | 15 | 24 | |

| 30 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 17 | |

| 31 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 24 | |

| 32 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 23 | |

| 33 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 16 | |

| 34 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 15 | |

| 35 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 12 | |

| 36 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | |

| 37 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | |

| 38 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 9 | |

| 39 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | |

| 40 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | |

| 41 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| 42 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 43 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 18 | |

| 44 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | |

| 45 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| 46 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| 47 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | |

| 48 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 49 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 51 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 | |

| 52 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| 53 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 54 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 7 | |

| 55 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| 56 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 57 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 58 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 61 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 62 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Totals (64 entries) | 3613 | 3608 | 3929 | 11150 | |

- ^[a] Totals for Ghana include all medals won as

.svg.png.webp) Gold Coast (GCO)

Gold Coast (GCO) - ^[b] Totals for Zimbabwe include all medals won as

.svg.png.webp) Southern Rhodesia (SRH)

Southern Rhodesia (SRH) - ^[c] Totals for Zambia include all medals won as

.svg.png.webp) Northern Rhodesia (NRH)

Northern Rhodesia (NRH) - ^[d] Totals for Sri Lanka include all medals won as

Ceylon (CEY)

Ceylon (CEY) - ^[e] Totals for Guyana include all medals won as

.svg.png.webp) British Guiana (BGU)

British Guiana (BGU)

Commonwealth sports

Unlike other sporting events, the Commonwealth Games have a flexible sporting program that respects the infrastructure and demands of the host city. This is also reflected in its holding dates, which may vary according to the weather conditions of each host city.Therefore, the program for each edition varies. Between 1930 and 1994, only individual events were part of the program and it was only in 1998 that authorization was given for the addition of team sports. It is common for each edition since then to have a list of seven to ten mandatory sports that must be played in this edition and must be approved 4 years in advance. Thus, the minimum number of sports per edition is 10 and the maximum is of 17. However, local demands can also increase the number of sports contested. Notable cases are freestyle wrestling in Delhi 2010 and beach volleyball in Gold Coast 2018. Special exceptions can also be made, such as the one in the last edition held in Birmingham, England, in which 3 extra sports were added to the program.[86] The current rules also determine gender parity, whereby men and women have an equal (or broadly equal) share of events.[87][88]

There are a total of 23 sports (with three multi-disciplinary sports) and a ten para-sports which are approved by the Commonwealth Games Federation.

|

|

In 2015, the Commonwealth Games Federation agreed large changes to the programme which increased the number of core sports, whilst removing a number of optionals, those removed are listed below.[91]

|

|

Sports such as the following are sports which have been analysed by the Commonwealth Games Federation but which are deemed to need expansion in areas such as participation levels within the Commonwealth both at a national (International Federation) and grassroots athletics level, Marketability, Television Rights, Equity, and Hosting Expenses, per Regulation 6 of the Commonwealth Games Constitution;[93] host nations may not pick these sports for their program until the Federation's requirements are fulfilled.[94]

|

|

Participation

Only six teams have attended every Commonwealth Games: Australia, Canada, England, New Zealand, Scotland, and Wales. Australia has been the highest scoring team for thirteen games, England for seven, and Canada for one.

Other countries that enter the games

Countries that have entered the games but no longer do so

• Host cities and year of games

Commonwealth nations yet to send teams

Very few Commonwealth dependencies and nations have yet to take part:[102][103]

- Gabon and Togo, the most recent members to join the Commonwealth in 2022 have not as of that date instigated Commonwealth Games federations in their nation. It is expected both nations will make their debut in 2026.

- Tokelau, a dependency of New Zealand was expected to take part the for the first time at the 2010 Games in Delhi but did not do so.

- Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha, former dependencies of Saint Helena and current parts of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, have never formed their own teams independent from the Saint Helena team.

- Other states, territories, and territorial autonomies with native populations within the Commonwealth that may be eligible include Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (territories of Australia), Nevis (a federal entity of the Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis), Rodrigues (Outer Islands of Mauritius), and Zanzibar (a semi-autonomous part of Tanzania).

- It is also conceivable that any future members of the Commonwealth such as applicants (for example South Sudan, Sudan and Yemen) may participate in future games. The Colony of Aden and Federation of South Arabia, precursors to modern Yemen, participated before in 1962 and in 1966. Sudan was an Anglo-Egyptian protectorate until independence in 1956.

- The Pitcairn Islands' tiny population (currently 50 to 60 people) would appear to prevent this British overseas territory from competing.

Controversies

Host city contract

The 1934 British Empire Games, originally awarded in 1930 to Johannesburg, were moved to London after South Africa's pre-apartheid government refused to allow participants of colour.[104]

The 2022 Commonwealth Games were originally awarded to Durban on 2 September 2015, at the CGF General Assembly in Auckland.[105] It was reported in February 2017 that Durban may be unable to host the games due to financial constraints. On 13 March 2017, the CGF stripped Durban of their rights to host and reopened the bidding process for the 2022 games.[106] Many cities from Australia, Canada, England and Malaysia expressed interest to host the games. However, the CGF received only one official bid and that was from Birmingham, England.[107] On 21 December 2017, Birmingham was awarded for the 2022 Games as Durban's replacement host.[108]

The state of Victoria, Australia was selected to host the 2026 Commonwealth Games. On 18 July 2023, the Premier of Victoria Dan Andrews announced the cancellation of the event in Victoria. Premier Andrews cited a significant increase in forecast cost for the reason suggesting the initial estimate of A$2.6 billion was likely to be closer to A$6–7 billion.[109][110]

Boycotts

Much like the Olympic Games, the Commonwealth Games have also experienced boycotts:

Nigeria boycotted the 1978 Commonwealth Games at Edmonton in protest of New Zealand's sporting contacts with apartheid-era South Africa. Uganda also stayed away, in protest of alleged Canadian hostility towards the government of Idi Amin.[36][111]

_boycotting_countries_(red).png.webp)

During the 1986 Commonwealth Games at Edinburgh, a majority of the Commonwealth nations staged a boycott, so that the Games appeared to be a whites-only event. Thirty two of the eligible fifty nine countries—largely African, Asian and Caribbean states—stayed away because of the Thatcher government's policy of keeping Britain's sporting links with apartheid South Africa in preference to participating in the general sporting boycott of that country. Consequently, Edinburgh 1986 witnessed the lowest number of athletes since Auckland 1950.[112] The boycotting nations were Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Belize, Cyprus, Dominica, Gambia, Ghana, Guyana, Grenada, India, Jamaica, Kenya, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Sierra Leone, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago, Tanzania, Turks and Caicos Islands, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[113] Bermuda was a particularly late withdrawal, as its athletes appeared in the opening ceremony and in the opening day of competition before the Bermuda Olympic Association decided to formally withdraw.[114]

Protests

The 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane took place amid mass protests for Australian aboriginal rights. The controversial Joh Bjelke-Petersen state government had been repeatedly been challenged by the Queensland Council for Civil Liberties over the restrictions it placed on freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom to protest. The Government of Queensland did not recognize Aboriginal land rights. Queensland also placed severe legal restrictions on Aboriginal people through the "Aboriginal Act 1971".

Aboriginal activists including Gary Foley planned mass demonstrations in Brisbane during the week of the games, dubbed the "Stolenwealth Games". In response, Queensland passed "The Commonwealth Games Act 1982" to restrict protests in or near the event. When Aboriginal activists and their supporters marched anyway, hundreds were arrested. The protests were recorded in the documentary "Guniwaya Ngigu".

Further "Stolenwealth Games" protests took place during the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne and 2018 Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast.[115]

Financial implications

The estimated cost of the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi was US$11 billion, according to Business Today magazine.[116] The initial total budget estimated by the Indian Olympic Association in 2003 was US$250 million. In 2010, however, the official total budget soon escalated to an estimated US$1.8 billion, a figure which excluded non-sports-related infrastructure development.[117] The 2010 Commonwealth Games is reportedly the most expensive Commonwealth Games ever.[118]

An analysis conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers on the 2002, 2006, 2014 and 2018 Commonwealth Games found that each dollar spent by governments on operating costs, games venues and athletes’ villages generated US$2 for the host city or state economies, with an average of more than 18,000 jobs generated by each of the events.[119][120] Additionally, all four cities enjoyed long-term improvements to transport or other infrastructure through hosting the Games, while some also benefited from the revival of struggling precincts.[121]

Notable competitors

Lawn bowler Willie Wood from Scotland was the first competitor to have competed in seven Commonwealth Games, from 1974 to 2002, a record equalled in 2014 by Isle of Man cyclist Andrew Roche.[122] They have both been surpassed by David Calvert of Northern Ireland who in 2018 attended his 11th games.[123]

Sitiveni Rabuka was a Prime Minister of Fiji. Beforehand he represented Fiji in shot put, hammer throw, discus and the decathlon at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games held in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Greg Yelavich, a sports shooter from New Zealand, has won 12 medals in seven games from 1986 to 2010.[124]

Lawn bowler Robert Weale has represented Wales in 8 Commonwealth Games, 1986–2014, winning 2 gold, 3 silver and 1 bronze.[125]

Nauruan weightlifter Marcus Stephen won twelve medals at the Games between 1990 and 2002, of which seven gold, and was elected President of Nauru in 2007. His performance has helped place Nauru (the smallest independent state in the Commonwealth, at 21 km2 (8.1 sq mi) and with a population of fewer than 9,400 in 2011) in twenty-second place on the all-time Commonwealth Games medal table.

Australian swimmer Ian Thorpe has won 10 Commonwealth Games gold medals and 1 silver medal. At the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur, he won 4 gold medals. At the 2002 Commonwealth Games in Manchester, he won 6 gold medals and 1 silver medal.[126]

Chad le Clos, South Africa's most decorated swimmer, has won 18 medals from four Commonwealth Games (2010, 2014, 2018 & 2022), seven of which are gold. At the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, he won two gold medals, one silver medal, and four bronze medals.[127] At the 2018 Commonwealth Games in Gold Coast, he won three golds, a silver and a bronze.[128]

English actor Jason Statham took part as a diver in the 1990 Commonwealth Games.[129]

At the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, Australian singer Cody Simpson won a gold medal as a swimmer at the men's 4 × 100 metre freestyle relay.[130]

See also

- African Games

- Asian Games

- Commonwealth Youth Games

- European Games

- Jeux de la Francophonie

- Lusophony Games

- Maccabiah Games

- Olympic Games

- Pacific Games

- Pan American Games

- Paralympic Games

- Winter Olympic Games

- Winter Paralympic Games

- Youth Olympic Games

- World Games

- Commonwealth Mountain and Ultradistance Running Championships

- List of Commonwealth Games venues

- List of stamps depicting the Commonwealth Games

- List of Commonwealth Games mascots

Notes

- ↑ which also refers itself as the Friendly Games[1][2] or simply the Comm Games.[3][4]

- 1 2 3 4 Aden later joined South Arabia in 1963 and departed the Commonwealth in 1967.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anguilla was completely separated from Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla in 1980 and remaining Saint Kitts and Nevis became independent from the United Kingdom in 1983.

- 1 2 3 4 British Honduras was renamed Belize in 1973.

- 1 2 3 4 British Guiana was renamed Guyana in 1966.

- 1 2 3 Ceylon was renamed Sri Lanka in 1972.

- 1 2 Fiji was re-suspended from the Commonwealth and the 2010 Games in 2009.[95] Fiji's suspension from the Commonwealth was lifted in time for the 2014 Games following democratic elections in March 2014.

- 1 2 The Gambia withdrew from the Commonwealth in 2013, but rejoined on 8 February 2018; The Gambia was readmitted to the Commonwealth Games Federation in March 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Gold Coast (British colony) was renamed Ghana in 1957.

- 1 2 3 4 Including neighbouring Islands.

- 1 2 Hong Kong was never a Commonwealth member but was a territory of a Commonwealth country; it ceased to be in the Commonwealth when the territory was handed over to China in 1997.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ireland was represented as a single team from the whole of the island in 1930, and by two teams, representing the Irish Free State, and Northern Ireland in 1934. The Irish Free State was officially renamed Éire in 1937 but did not participate in the 1938 Games, and withdrew from the Commonwealth when it unilaterally declared that it was the Republic of Ireland on 18 April 1949.

- 1 2 Contemporary illustrations show Green Flag used for the Irish team.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore federated as Malaysia in 1963. Singapore was expelled from the federation in 1965, becoming a sovereign country.

- 1 2 Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949.[99]

- 1 2 The Ulster Banner was the flag of the former Government of Northern Ireland only between 1953 and 1972, but the flag has been regarded as flag of Northern Ireland since 1924 among unionists and loyalists. The Ulster Banner is the sporting flag of Northern Ireland in other events such as the FIFA World Cup and in the FIVB Volleyball World Championship.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia competed separately in 1954 and 1958 while both were part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia federated with Nyasaland in 1953 as Rhodesia and Nyasaland, which dissolved at the end of 1963 and became Zambia in 1964.

- 1 2 Under the name of "Saint Helena" in the Commonwealth Games.[101] Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha were dependencies of Saint Helena, so the territory was officially called "Saint Helena and Dependencies" until 2009. Saint Helena, Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha became equal parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha in 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Western Samoa was renamed Samoa in 1997.

- 1 2 Swaziland was renamed Eswatini in 2018.

- 1 2 Zanzibar and Tanganyika federated to form Tanzania in 1964.

- 1 2 Zimbabwe withdrew from the Commonwealth in 2003.

- ↑ The Maldives withdrew from the Commonwealth in 2016,[96] but was re-admitted in 2020.[97][98]

- ↑ United Kingdom were the host of the Inter-Empire Championships in 1911. This event was held before the 1st edition of the Games held in Hamilton, Canada in 1930.

References

- ↑ "History of the Games". Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Keating, Steve (31 July 2022). "'Friendly Games' have an edge when India play Pakistan at cricket". Reuters. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ↑ "Comm Games Chairman Peter Beattie Apologies For Closing Ceremony Blunder". Triple M. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ↑ Allan, Steve. "COMM GAMES UNDERWAY FOR COAST ATHLETES | NBN News". Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Commonwealth Games Federation – The Story of The Commonwealth Games". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Para-Sports at the Commonwealth Games". Commonwealth Sport. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ "Gender Equality | Commonwealth Games Federation". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- 1 2 Jamie Bradburn (21 July 2015). "The British Empire Games of 1930". Torontoist.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Paraplegic Games". disabilitysport.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022 | Commonwealth Games Federation". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ↑ "Home of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games". Commonwealth Games - Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games: A brief history, editions and hosts". Olympics. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ↑ "The Commonwealth Games is on its last legs — but could it be saved with a left-field idea?". ABC News. 5 December 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ↑ "J Astley Cooper". Anent Scottish Running. 25 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ Arnd Krüger (1986): War John Astley Cooper der Erfinder der modernen Olympischen Spiele? In: LOUIS BURGENER u. a. (Hrsg.): Sport und Kultur, Bd. 6. Bern: Lang, 72 – 81.

- ↑ Riordan, Jim (11 September 2002). The International Politics of Sport in the Twentieth Century. Taylor & Francis. p. 4. ISBN 9781135817275.

- ↑ Dunn, John F. (16 March 1986). "STAMPS; NEW BOOKLET". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ "FESTIVAL OF EMPIRE GAMES". Evening Journal (Adelaide). 21 April 1911. p. 2. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ↑ "COMMONWEALTH GAMES MEDALLISTS". GBR Athletics. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ "Empire Sports". Papers Past. 21 August 1911. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ Griffin, Frederick (9 August 1930). "Hamilton's Amazing Empire Athletic Meet". Winnipeg Free Press. Winnipeg, Manitoba. p. 27. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- 1 2 "History of the Commonwealth Games". Topend Sports. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ "Hamilton 1930". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- 1 2 "1930 Empire Games". Anent Scottish Running. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ "Hamilton 1930". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "London 1934". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Sydney 1938". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Auckland 1950". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Vancouver 1954". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Cardiff 1958". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Brown and Hogsbjerg, Apartheid is not a game, 16

- ↑ "Perth 1962". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Kingston 1966". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Edinburgh 1970". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Christchurch 1974". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- 1 2 Donald Macintosh; Michael Hawes; Donna Ruth Greenhorn; David Ross Black (5 April 1994). Sport and Canadian Diplomacy. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-7735-1161-3. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ "Edmonton 1978". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Brisbane 1982". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Edinburgh 1986". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Auckland 1990". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Pakistan". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ "Victoria 1994". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Kuala Lumpur 1998". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Manchester 2002". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Melbourne 2006". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Delhi 2010". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Rwanda". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ "Usain Bolt: Glasgow 2014 gold for Jamaica in 4x100m relay". BBC Sport. 2 August 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Glasgow 2014". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Gold Coast 2018 to offer same amount of medals for men and women after seven events added". Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Gold Coast 2018". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Victoria signs agreement to host 2026 Commonwealth Games". Inside The Games. 15 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Australia's Victoria state pulls out of hosting 2026 Commonwealth Games". Sky News. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "Canadian province Alberta cancels bid for 2030 Commonwealth Games". BBC News. 4 August 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ McElwee, Molly (4 August 2023). "Commonwealth Games are dying before our eyes". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ↑ DePauw, Karen P; Gavron, Susan J (2005). Disability sport. Human Kinetics. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-7360-4638-1. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ Van Ooyen and Justin Anjema, Mark; Anjema, Justin (25 March 2004). "A Review and Interpretation of the Events of the 1994 Commonwealth Games" (PDF). Redeemer University College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Para-sports for elite athletes with a disability". Commonwealth Games Federation website. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "IPC and CGF Sign Co-operative Agreement". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ↑ Semanticus.info, T.D. Richardson Archived 26 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 7 July 2012)

- ↑ CBC News, Canadian Ski Museum in trouble, 15 March 2011, Ashley Burke (accessed 7 July 2012)

- ↑ NZ Collector Services St. Moritz 1958 Commonwealth Winter Games silver medal Archived 16 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 7 July 2012)

- ↑ Antiques Reporter, St. Mortiz 1966 Commonwealth Winter Games bronze medal Archived 30 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 7 July 2012)

- ↑ "Commonwealth Youth Games – About the Games". bendigo2004.thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – The Role of The CGF". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ↑ "Contact Information". Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Contact | Royal Commonwealth Society". thercs.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Contact us – CLGF". clgf.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – Sports Contacts". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – CGA Contacts". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ "CGF Constitution" (PDF). Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ "Queen's Baton Relay: The tradition continues..." Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ↑ "Design and route for Gold Coast 2018 Queen's Baton Relay revealed". 20 November 2016. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "The CWG opening show reality: Rs 350 crore". The Times of India Blog. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ↑ "Constitution | Commonwealth Games Federation" (PDF). CGF. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2019.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – Oath & Award". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "11 Things You Didn't Know about National Anthems". Commonwealth Games - Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ↑ Sir Andrew Foster (30 May 2010). "England announce victory anthem for Delhi chosen by the public! – Commonwealth Games England". Weare England. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- 1 2 "History of God Defend New Zealand | Ministry for Culture and Heritage". mch.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ↑ "Games team picks new Scots anthem". BBC News. 9 January 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ "Inter-Empire Championships". Auckland Star. 4 August 1911. p. 7. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ The Complete Book of The Commonwealth Games (Gold Coast Edition) by Graham Groom (2017)

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022". Commonwealth Sport. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ↑ "Victoria axes Commonwealth Games plans due to financial constraints, Daniel Andrews confirms..." Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 18 July 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Charter" (PDF). thecgf.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ↑ "Level playing field for women at 2018 Commonwealth Games". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, Scotland. 7 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ McKay, Duncan (7 October 2016). "Gold Coast 2018 to offer same amount of medals for men and women after seven events added". Insidethegames.biz. Dunsar Media. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Elite Athletes with a Disability (EAD)". Commonwealth Sports. Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Sports Programme". Commonwealth Sports. Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018.

- ↑ Avison, Ben (2 April 2015). "Commonwealth Games transformed to attract aspiring cities". Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ "Canoeing closer to being a full-medal event". Commonwealthdelhi2010.blogspot.com. 11 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ . Archived 13 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Commonwealth Games Federation. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ↑ Sports Programme Archived 2 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Commonwealth Games Federation. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ "Fiji suspended from Commonwealth". The New Zealand Herald. 2 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ↑ Mackay, Duncan (14 October 2016). "Maldives set to miss Gold Coast 2018 after resigning from Commonwealth". insidethegames.biz/. Dunsar Media. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Palmer, Dan (31 August 2020). "Maldives readmitted as member of Commonwealth Games Federation". insidethegames.biz.

- ↑ "Maldives re-joins as member of Commonwealth Games Federation". thecgf.com. Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF). Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "Terms of Union". Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ↑ "Norfolk Island". Gold Coast 2018 XXI Commonwealth Games. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – Commonwealth Countries". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ ""The future of the modern Commonwealth: Widening vs. deepening?". Commonwealth Policy Studies Unit. Archived from the original (doc) on 23 July 2011". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Non-Participating Countries". topendsports.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ Gorman, Daniel (31 July 2012). The Emergence of International Society in the 1920s. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 9781107021136. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games: Durban confirmed as 2022 host city". BBC Sport. 2 September 2015. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games: Durban, South Africa will not host Games in 2022". BBC Sport. 13 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games 2022: Birmingham only bidder for event". BBC Sport. 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Kelner, Martha (21 December 2017). "Birmingham officially named as 2022 Commonwealth Games host city". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games: 2026 event in doubt after Victoria cancels". BBC News. 18 July 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ↑ Pender, Kieran (18 July 2023). "Does Victoria's 2026 cancellation sound Commonwealth Games death knell?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – 1978 Commonwealth Games – Introduction". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish independence referendum will increase interest in Glasgow 2014, it is claimed | Glasgow 2014". insidethegames.biz. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ "8 More Nations Join Boycott of Commonwealth Games; Total Now 23". Los Angeles Times. Reuters. 20 July 1986. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ Fraser, Graham (25 April 2014). "Glasgow 2014: The Bermuda boycott of 1986 that still hurts". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ Latimore, Jack (9 April 2018). "'The fight never left': Stolenwealth Games protesters draw on long tradition". Guardian, The. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ↑ "Delhi Commonwealth Games organiser arrested in corruption investigation". The Guardian. Associated Press. 25 April 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Ravi Shankar; Mihir Srivastava (7 August 2010). "Payoffs & bribes cast a shadow on CWG: Sport : India Today". India Today. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ↑ Melbourne 2006

- ↑ "New report reveals Commonwealth Games consistently provides over £1 billion boost for host cities". The Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Value Framework" (PDF). The Commonwealth Games Federation. PricewaterhouseCoopers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ Towell, Noel (16 February 2022). "Games can deliver gold for Victoria's economy". The Age. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Glasgow 2014: Mark Cavendish relishes idea of racing with mates". BBC Sport. 10 May 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games: TeamNI announced for Gold Coast 2018". Portadown Times. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ↑ "Greg Yelavich". New Zealand Olympic Team. 9 February 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ↑ "Weale's Commonwealth Games memories". BBC Sport. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games Federation – Inspiring Athletes – Commonwealth Legend". thecgf.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "Chad le Clos stars at Commonwealth Games with record 7 medals". News24. 30 July 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ↑ "About Me – Chad Le Clos". Chad Le Clos. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Shivangi Jalan (4 April 2018). "When Jason Statham participated in the 1990 Commonwealth Games". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ Ramsay, George (28 July 2022). "Cody Simpson returned to his 'first love' by swapping his music career for swimming and is set to compete at the Commonwealth Games". CNN. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

Sources

- Brown, Geoff and Hogsbjerg, Christian. Apartheid is not a Game: Remembering the Stop the Seventy Tour campaign. London: Redwords, 2020. ISBN 9781912926589.

Further reading

- Phillips, Bob. Honour of Empire, Glory of Sport: the history of athletics at the Commonwealth Games. Manchester: Parrswood Press, 2000. ISBN 9781903158098.

External links

- Official website

- Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) at the Commonwealth website Archived 23 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "Commonwealth Games". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Commonwealth Games at Curlie

- insidethegames – the latest and most up to date news and interviews from the world of Olympic, Commonwealth and Paralympic Games

- ATR – Around the Rings – the Business Surrounding the Multi-sport events

- GamesBids.com – An Authoritative Review of Games Bid Business (home of the BidIndex™)