Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 (CXCL9) is a small cytokine belonging to the CXC chemokine family that is also known as monokine induced by gamma interferon (MIG). The CXCL9 is one of the chemokine which plays role to induce chemotaxis, promote differentiation and multiplication of leukocytes, and cause tissue extravasation.[3]

The CXCL9/CXCR3 receptor regulates immune cell migration, differentiation, and activation. Immune reactivity occurs through recruitment of immune cells, such as cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs), natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and macrophages. Th1 polarization also activates the immune cells in response to IFN-γ.[4] Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a key for clinical outcomes and prediction of the response to checkpoint inhibitors.[5] In vivo studies suggest the axis plays a tumorigenic role by increasing tumor proliferation and metastasis. CXCL9 predominantly mediates lymphocytic infiltration to the focal sites and suppresses tumor growth.[6]

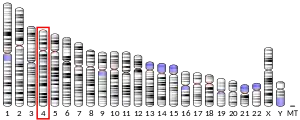

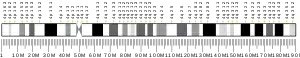

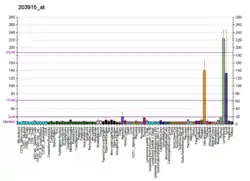

It is closely related to two other CXC chemokines called CXCL10 and CXCL11, whose genes are located near the gene for CXCL9 on human chromosome 4.[7][8] CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 all elicit their chemotactic functions by interacting with the chemokine receptor CXCR3.[9]

Biomarkers

CXCL9, -10, -11 have proven to be valid biomarkers for the development of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction, suggesting an underlining pathophysiological relation between levels of these chemokines and the development of adverse cardiac remodeling.[10][11]

This chemokine has also been associated as a biomarker for diagnosing Q fever infections.[12]

Interactions

CXCL9 in immune reactions

For immune cell differentiation, some reports show that CXCL9 lead to Th1 polarization through CXCR3.[15] In vivo model by Zohar et al. showed that CXCL9, drove increased transcription of T-bet and RORγ, leading to the polarization of Foxp3− type 1 regulatory (Tr1) cells or T helper 17 (Th17) from naive T cells via STAT1, STAT4, and STAT5 phosphorylation.[15]

Several studies have shown that tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) play modulatory activities in the TME, and the CXCL9/CXCR3 axis impacts TAMs polarization. The TAMs have opposite effects; M1 for anti-tumor activities, and M2 for pro-tumor activities. Oghumu et al. clarified that CXCR3 deficient mice displayed increased IL-4 production and M2 polarization in a murine breast cancer model, and decreased innate and immune cell-mediated anti-tumor responses.[16]

For immune cell activation, CXCL9 stimulate immune cells through Th1 polarization and activation. Th1 cells produce IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2 and enhance anti-tumor immunity by stimulating CTLs, NK cells and macrophages.[17] The IFN-γ-dependent immune activation loop also promotes CXCL9 release.[3]

Immune cells, like Th1, CTLs, NK cells, and NKT cells, show anti-tumor effect against cancer cells through paracrine CXCL9/CXCR3 in tumor models.[6] The autocrine CXCL9/CXCR3 signaling in cancer cells increases cancer cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis.

CXCL9/CXCR3 and the PDL-1/PD-1

The relationship between CXCL9/CXCR3 and the PDL-1/PD-1 is an important area of research. Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) shows increased expression on T cells at the tumor site compared to T cells present in the peripheral blood, and anti-PD-1 therapy can inhibit “immune escape” and the immune activation.[18] Peng et al. showed that anti-PD-1 could not only enhance T cell-mediated tumor regression but also increase the expression of IFN-γ but not CXCL9 by bone marrow–derived cells.[18] Blockade of the PDL-1/PD-1 axis in T cells may trigger a positive feedback loop at the tumor site through the CXCL9/CXCR3 axis. Also using anti-CTLA4 antibody, this axis was significantly up-regulated in pretreatment melanoma lesions in patients with good clinical response after ipilimumab administration.[19]

CXCL9 and melanoma

CXCL9 has also been identified as candidate biomarker of adoptive T cell transfer therapy in metastatic melanoma.[20] The role of CXCL9/CXCR3 in TME and immune response - this plays a critical role in immune activation through paracrine signaling, impacting efficacy of cancer treatments.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000138755 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- 1 2 3 Tokunaga R, Zhang W, Naseem M, Puccini A, Berger MD, Soni S, McSkane M, Baba H, Lenz HJ (February 2018). "CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 axis for immune activation - A target for novel cancer therapy". Cancer Treatment Reviews. 63: 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.007. PMC 5801162. PMID 29207310.

- ↑ Schoenborn, Jamie R.; Wilson, Christopher B. (2007), Regulation of Interferon‐γ During Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses, Advances in Immunology, vol. 96, Elsevier, pp. 41–101, doi:10.1016/s0065-2776(07)96002-2, ISBN 9780123737090, PMID 17981204

- ↑ Fernandez-Poma SM, Salas-Benito D, Lozano T, Casares N, Riezu-Boj JI, Mancheño U, Elizalde E, Alignani D, Zubeldia N, Otano I, Conde E, Sarobe P, Lasarte JJ, Hervas-Stubbs S (July 2017). "+ T cells Expressing PD-1 Improves the Efficacy of Adoptive T-cell Therapy". Cancer Research. 77 (13): 3672–3684. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0236. PMID 28522749.

- 1 2 Gorbachev, A. V.; Kobayashi, H.; Kudo, D.; Tannenbaum, C. S.; Finke, J. H.; Shu, S.; Farber, J. M.; Fairchild, R. L. (2007-02-15). "CXC Chemokine Ligand 9/Monokine Induced by IFN- Production by Tumor Cells Is Critical for T Cell-Mediated Suppression of Cutaneous Tumors". The Journal of Immunology. 178 (4): 2278–2286. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2278. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 17277133.

- ↑ Lee HH, Farber JM (1996). "Localization of the gene for the human MIG cytokine on chromosome 4q21 adjacent to INP10 reveals a chemokine "mini-cluster"". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 74 (4): 255–8. doi:10.1159/000134428. PMID 8976378.

- ↑ O'Donovan N, Galvin M, Morgan JG (1999). "Physical mapping of the CXC chemokine locus on human chromosome 4". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 84 (1–2): 39–42. doi:10.1159/000015209. PMID 10343098. S2CID 8087808.

- ↑ Tensen CP, Flier J, Van Der Raaij-Helmer EM, Sampat-Sardjoepersad S, Van Der Schors RC, Leurs R, Scheper RJ, Boorsma DM, Willemze R (May 1999). "Human IP-9: A keratinocyte-derived high affinity CXC-chemokine ligand for the IP-10/Mig receptor (CXCR3)". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 112 (5): 716–22. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00581.x. PMID 10233762.

- ↑ Altara R, Gu YM, Struijker-Boudier HA, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Blankesteijn WM (2015). "Left Ventricular Dysfunction and CXCR3 Ligands in Hypertension: From Animal Experiments to a Population-Based Pilot Study". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0141394. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1041394A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141394. PMC 4624781. PMID 26506526.

- ↑ Altara R, Manca M, Hessel MH, Gu Y, van Vark LC, Akkerhuis KM, Staessen JA, Struijker-Boudier HA, Booz GW, Blankesteijn WM (August 2016). "CXCL10 Is a Circulating Inflammatory Marker in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure: a Pilot Study". Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research. 9 (4): 302–14. doi:10.1007/s12265-016-9703-3. PMID 27271043. S2CID 41188765.

- ↑ Jansen AF, Schoffelen T, Textoris J, Mege JL, Nabuurs-Franssen M, Raijmakers RP, Netea MG, Joosten LA, Bleeker-Rovers CP, van Deuren M (August 2017). "CXCL9, a promising biomarker in the diagnosis of chronic Q fever". BMC Infectious Diseases. 17 (1): 556. doi:10.1186/s12879-017-2656-6. PMC 5551022. PMID 28793883.

- ↑ Lasagni L, Francalanci M, Annunziato F, Lazzeri E, Giannini S, Cosmi L, Sagrinati C, Mazzinghi B, Orlando C, Maggi E, Marra F, Romagnani S, Serio M, Romagnani P (June 2003). "An alternatively spliced variant of CXCR3 mediates the inhibition of endothelial cell growth induced by IP-10, Mig, and I-TAC, and acts as functional receptor for platelet factor 4". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (11): 1537–49. doi:10.1084/jem.20021897. PMC 2193908. PMID 12782716.

- ↑ Weng Y, Siciliano SJ, Waldburger KE, Sirotina-Meisher A, Staruch MJ, Daugherty BL, Gould SL, Springer MS, DeMartino JA (July 1998). "Binding and functional properties of recombinant and endogenous CXCR3 chemokine receptors". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (29): 18288–91. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.29.18288. PMID 9660793.

- 1 2 Zohar Y, Wildbaum G, Novak R, Salzman AL, Thelen M, Alon R, Barsheshet Y, Karp CL, Karin N (May 2014). "CXCL11-dependent induction of FOXP3-negative regulatory T cells suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (5): 2009–22. doi:10.1172/JCI71951. PMC 4001543. PMID 24713654.

- ↑ Oghumu S, Varikuti S, Terrazas C, Kotov D, Nasser MW, Powell CA, Ganju RK, Satoskar AR (September 2014). "CXCR3 deficiency enhances tumor progression by promoting macrophage M2 polarization in a murine breast cancer model". Immunology. 143 (1): 109–19. doi:10.1111/imm.12293. PMC 4137960. PMID 24679047.

- ↑ Mosser DM, Edwards JP (December 2008). "Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 8 (12): 958–69. doi:10.1038/nri2448. PMC 2724991. PMID 19029990.

- 1 2 Peng W, Liu C, Xu C, Lou Y, Chen J, Yang Y, Yagita H, Overwijk WW, Lizée G, Radvanyi L, Hwu P (October 2012). "PD-1 blockade enhances T-cell migration to tumors by elevating IFN-γ inducible chemokines". Cancer Research. 72 (20): 5209–18. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1187. PMC 3476734. PMID 22915761.

- ↑ Ji RR, Chasalow SD, Wang L, Hamid O, Schmidt H, Cogswell J, Alaparthy S, Berman D, Jure-Kunkel M, Siemers NO, Jackson JR, Shahabi V (July 2012). "An immune-active tumor microenvironment favors clinical response to ipilimumab". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 61 (7): 1019–31. doi:10.1007/s00262-011-1172-6. PMID 22146893. S2CID 8464711.

- ↑ Bedognetti D, Spivey TL, Zhao Y, Uccellini L, Tomei S, Dudley ME, Ascierto ML, De Giorgi V, Liu Q, Delogu LG, Sommariva M, Sertoli MR, Simon R, Wang E, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM (October 2013). "CXCR3/CCR5 pathways in metastatic melanoma patients treated with adoptive therapy and interleukin-2". British Journal of Cancer. 109 (9): 2412–23. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.557. PMC 3817317. PMID 24129241.

Further reading

- Farber JM (July 1990). "A macrophage mRNA selectively induced by gamma-interferon encodes a member of the platelet factor 4 family of cytokines". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (14): 5238–42. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.5238F. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.14.5238. PMC 54298. PMID 2115167.

- Liao F, Rabin RL, Yannelli JR, Koniaris LG, Vanguri P, Farber JM (November 1995). "Human Mig chemokine: biochemical and functional characterization". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 182 (5): 1301–14. doi:10.1084/jem.182.5.1301. PMC 2192190. PMID 7595201.

- Farber JM (April 1993). "HuMig: a new human member of the chemokine family of cytokines". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 192 (1): 223–30. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.1403. PMID 8476424.

- Erdel M, Laich A, Utermann G, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G (1998). "The human gene encoding SCYB9B, a putative novel CXC chemokine, maps to human chromosome 4q21 like the closely related genes for MIG (SCYB9) and INP10 (SCYB10)". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 81 (3–4): 271–2. doi:10.1159/000015043. PMID 9730616. S2CID 46846304.

- Jenh CH, Cox MA, Kaminski H, Zhang M, Byrnes H, Fine J, Lundell D, Chou CC, Narula SK, Zavodny PJ (April 1999). "Cutting edge: species specificity of the CC chemokine 6Ckine signaling through the CXC chemokine receptor CXCR3: human 6Ckine is not a ligand for the human or mouse CXCR3 receptors". Journal of Immunology. 162 (7): 3765–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.162.7.3765. PMID 10201891. S2CID 23946439.

- Rabin RL, Park MK, Liao F, Swofford R, Stephany D, Farber JM (April 1999). "Chemokine receptor responses on T cells are achieved through regulation of both receptor expression and signaling". Journal of Immunology. 162 (7): 3840–50. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.162.7.3840. PMID 10201901. S2CID 39401025.

- Shields PL, Morland CM, Salmon M, Qin S, Hubscher SG, Adams DH (December 1999). "Chemokine and chemokine receptor interactions provide a mechanism for selective T cell recruitment to specific liver compartments within hepatitis C-infected liver". Journal of Immunology. 163 (11): 6236–43. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.163.11.6236. PMID 10570316. S2CID 37624763.

- Jinquan T, Jing C, Jacobi HH, Reimert CM, Millner A, Quan S, Hansen JB, Dissing S, Malling HJ, Skov PS, Poulsen LK (August 2000). "CXCR3 expression and activation of eosinophils: role of IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 and monokine induced by IFN-gamma". Journal of Immunology. 165 (3): 1548–56. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1548. PMID 10903763.

- Loetscher P, Pellegrino A, Gong JH, Mattioli I, Loetscher M, Bardi G, Baggiolini M, Clark-Lewis I (February 2001). "The ligands of CXC chemokine receptor 3, I-TAC, Mig, and IP10, are natural antagonists for CCR3". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (5): 2986–91. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005652200. PMID 11110785.

- Romagnani P, Annunziato F, Lazzeri E, Cosmi L, Beltrame C, Lasagni L, Galli G, Francalanci M, Manetti R, Marra F, Vanini V, Maggi E, Romagnani S (February 2001). "Interferon-inducible protein 10, monokine induced by interferon gamma, and interferon-inducible T-cell alpha chemoattractant are produced by thymic epithelial cells and attract T-cell receptor (TCR) alphabeta+ CD8+ single-positive T cells, TCRgammadelta+ T cells, and natural killer-type cells in human thymus". Blood. 97 (3): 601–7. doi:10.1182/blood.V97.3.601. PMID 11157474.

- Dwinell MB, Lügering N, Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF (January 2001). "Regulated production of interferon-inducible T-cell chemoattractants by human intestinal epithelial cells". Gastroenterology. 120 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1053/gast.2001.20914. PMID 11208713.

- Lambeir AM, Proost P, Durinx C, Bal G, Senten K, Augustyns K, Scharpé S, Van Damme J, De Meester I (August 2001). "Kinetic investigation of chemokine truncation by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV reveals a striking selectivity within the chemokine family". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (32): 29839–45. doi:10.1074/jbc.M103106200. PMID 11390394.

- Stoof TJ, Flier J, Sampat S, Nieboer C, Tensen CP, Boorsma DM (June 2001). "The antipsoriatic drug dimethylfumarate strongly suppresses chemokine production in human keratinocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells". The British Journal of Dermatology. 144 (6): 1114–20. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04220.x. PMID 11422029. S2CID 26364400.

- Campbell JD, Stinson MJ, Simons FE, Rector ES, HayGlass KT (July 2001). "In vivo stability of human chemokine and chemokine receptor expression". Human Immunology. 62 (7): 668–78. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00260-9. PMID 11423172.

- Scapini P, Laudanna C, Pinardi C, Allavena P, Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Cassatella MA (July 2001). "Neutrophils produce biologically active macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha (MIP-3alpha)/CCL20 and MIP-3beta/CCL19". European Journal of Immunology. 31 (7): 1981–8. doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<1981::AID-IMMU1981>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 11449350.

- Gillitzer R (August 2001). "Inflammation in human skin: a model to study chemokine-mediated leukocyte migration in vivo". The Journal of Pathology. 194 (4): 393–4. doi:10.1002/1096-9896(200108)194:4<393::AID-PATH907>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 11523044. S2CID 32739376.

- Romagnani P, Rotondi M, Lazzeri E, Lasagni L, Francalanci M, Buonamano A, Milani S, Vitti P, Chiovato L, Tonacchera M, Bellastella A, Serio M (July 2002). "Expression of IP-10/CXCL10 and MIG/CXCL9 in the thyroid and increased levels of IP-10/CXCL10 in the serum of patients with recent-onset Graves' disease". The American Journal of Pathology. 161 (1): 195–206. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64171-5. PMC 1850693. PMID 12107104.

External links

- Human CXCL9 genome location and CXCL9 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.