| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Estulic, Intuniv, Tenex, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601059 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Centrally acting alpha-2a adrenergic receptor agonist |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80–100% (IR), 58% (XR)[3][4] |

| Protein binding | 70%[3][4] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4[3][4] |

| Elimination half-life | IR: 10-17 hours; XR: 17 hours (10-30) in adults & adolescents and 14 hours in children[3][4][5][6] |

| Excretion | Kidney (80%; 50% [range: 40–75%] as unchanged drug)[3][4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.933 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

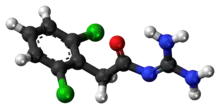

| Formula | C9H9Cl2N3O |

| Molar mass | 246.09 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Guanfacine, sold under the brand name Tenex (immediate-release) and Intuniv (extended-release) among others, is an oral alpha-2a agonist medication used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and high blood pressure.[2][7] Guanfacine is FDA-approved for monotherapy treatment of ADHD,[2] as well as being used for augmentation of other treatments, such as stimulants.[7] Guanfacine is also used off-label to treat tic disorders, anxiety disorders and PTSD.[8]

Common side effects include sleepiness, constipation, and dry mouth.[7] Other side effects may include low blood pressure and urinary problems.[9] The FDA has categorized Guanfacine as "Category B" in pregnancy, which means animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk or an adverse effect during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[10][9] It appears to work by activating the α2A receptors in the brain, thereby decreasing sympathetic nervous system activity.[7]

Guanfacine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1986.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[7] In 2020, it was the 300th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical uses

Guanfacine is FDA-approved as monotherapy or augmentation with stimulants to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[2][13][14] Unlike stimulant medications, guanfacine is regarded as having no abuse potential, and may even be used to reduce abuse of drugs including nicotine and cocaine.[15] It is also FDA approved to treat high blood pressure.[4] Guanfacine can offer a synergistic enhancement of stimulants such as amphetamines and methylphenidate for treating ADHD, and in many cases can also help control the side effect profile of stimulant medications.[7] Guanfacine is also used off-label to treat tic disorders, anxiety disorders, and PTSD.[8]

An off-label use of guanfacine is for the treatment of anxiety, such as generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Guanfacine and other α2A agonists have anxiolytic-like action,[16] thereby reducing the emotional responses of the amygdala, and strengthening prefrontal cortical regulation of emotion, action and thought.[17] These actions arise from both inhibition of stress-induced catecholamine release, and from prominent, post-synaptic actions in the prefrontal cortex.[17] Due to its prolonged half-life, it also has been seen to improve sleep interrupted by nightmares in PTSD patients.[18] All of these actions likely contribute to the relief of the hyperarousal, re-experiencing of memory, and impulsivity associated with PTSD.[19] Guanfacine appears to be especially helpful in treating children who have been traumatized or abused.[17]

Adverse effects

Side effects of guanfacine are dose-dependent.[20]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include sleepiness, tiredness, headache, and stomach ache.[21]

Common (1–10% incidence) adverse effects include decreased appetite, nausea, dry mouth, urinary incontinence, and rashes.[21]

Interactions

Guanfacine availability is significantly affected by the CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 enzymes. Medications that inhibit or induce those enzymes change the amount of guanfacine in circulation and thus its efficacy and rate of adverse effects. Because of its impact on the heart, it should be used with caution with other cardioactive drugs. A similar concern is appropriate when it is used with sedating medications.[21]

Pharmacology

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| α2A | 50.3 – 93.3 | Human | [23][24] |

| α2B | 1,020 – 1,380 | Human | [23][24] |

| α2C | 1,120 – 3,890 | Human | [23][24] |

| The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Guanfacine is a highly selective agonist of the α2A adrenergic receptor, with low affinity for other receptors.[22] However it may also be a potent 5-HT2B receptor agonist, which can be associated with valvulopathy, although not all 5-HT2B agonists have this effect.[25]

Mechanism of action

Guanfacine works by activating α2A adrenoceptors[26] within the central nervous system. This leads to reduced peripheral sympathetic outflow and thus a reduction in peripheral sympathetic tone, which lowers both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.[27]

In ADHD, guanfacine works by strengthening the regulation of attention and behavior by the prefrontal cortex.[28] These enhancing effects on prefrontal cortical functions are believed to be due to drug stimulation of post-synaptic α2A adrenoceptors on dendritic spines. cAMP-mediated opening of HCN and KCNQ channels is inhibited, which enhances prefrontal cortical synaptic connectivity and neuronal firing.[28][29] The use of guanfacine for treating prefrontal disorders was developed by the Arnsten Lab at Yale University.[28][30]

Pharmacokinetics

Guanfacine has an oral bioavailability of 80%. There is no clear evidence of any first-pass metabolism. Elimination half-life is 17 hours with the major elimination route being renal. The principal metabolite is the 3-hydroxy-derivative, with evidence of moderate biotransformation, and the key intermediate is an epoxide.[31] Elimination is not impacted by impaired renal function. As such, metabolism by the liver is the assumption for those with impaired renal function, as supported by the increased frequency of known side effects of orthostatic hypotension and sedation.[32]

History

In 1986, guanfacine was approved by the FDA for the treatment of hypertension under the brand name Tenex (Drugs@FDA). In 2010, guanfacine was approved by the FDA for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder for people 6–17 years old.[13] It was approved for ADHD by the European Medicines Agency under the name Intuniv in 2015.[33] It was added to the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for the treatment of ADHD in 2018.[34]

Brand names

Brand names include Tenex, Afken, Estulic, and Intuniv (an extended release formulation).

Research

Guanfacine has been studied as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Evidence of efficacy in adults is limited, but one study found positive results in children with comorbid ADHD.[35] It may be also useful in adult PTSD patients who do not respond to SSRIs.[36]

Results of studies using guanfacine to treat Tourette's have been mixed.[37]

Guanfacine has been investigated for treatment of withdrawal for opioids, ethanol, and nicotine.[38] Guanfacine has been shown to help reduce stress-induced craving of nicotine in smokers trying to quit, which may involve strengthening of prefrontal cortex mediated self-control.[39]

References

- ↑ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Intuniv- guanfacine tablet, extended release Intuniv- guanfacine kit". DailyMed. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Guanfacine (guanfacine) Tablet [Genpharm Inc.]". DailyMed. Genpharm Inc. March 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "guanfacine (Rx) - Intuniv, Tenex". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ↑ Hofer KN, Buck ML (2008). "New Treatment Options for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Part II. Guanfacine". Pediatric Pharmacotherapy (14): 4. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ Cruz MP (August 2010). "Guanfacine Extended-Release Tablets (Intuniv), a Nonstimulant Selective Alpha(2A)-Adrenergic Receptor Agonist For Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". P & T. 35 (8): 448–451. PMC 2935643. PMID 20844694.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Guanfacine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- 1 2 Boland RJ, Verduin ML, Sadock BJ (2023). Ruiz P (ed.). Kaplan & Sadock's Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry (5th ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 1811–1812. ISBN 978-1-9751-6748-6. OCLC 1264172789. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 British national formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 349–350. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ "Patient Information. INTUNIV (in-TOO-niv) (guanfacine). Extended-Release Tablets" (PDF). FDA.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ "Guanfacine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- 1 2 Kornfield R, Watson S, Higashi AS, Conti RM, Dusetzina SB, Garfield CF, et al. (April 2013). "Effects of FDA advisories on the pharmacologic treatment of ADHD, 2004-2008". Psychiatric Services. 64 (4): 339–346. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200147. PMC 4023684. PMID 23318985.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Zito JM, Derivan AT, Kratochvil CJ, Safer DJ, Fegert JM, Greenhill LL (September 2008). "Off-label psychopharmacologic prescribing for children: history supports close clinical monitoring". Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-24. PMC 2566553. PMID 18793403.

- ↑ Clemow DB, Walker DJ (September 2014). "The potential for misuse and abuse of medications in ADHD: a review". Postgraduate Medicine. 126 (5): 64–81. doi:10.3810/pgm.2014.09.2801. PMID 25295651. S2CID 207580823.

- ↑ Morrow BA, George TP, Roth RH (November 2004). "Noradrenergic alpha-2 agonists have anxiolytic-like actions on stress-related behavior and mesoprefrontal dopamine biochemistry". Brain Research. 1027 (1–2): 173–178. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.057. PMID 15494168. S2CID 7066842.

- 1 2 3 Arnsten AF, Raskind MA, Taylor FB, Connor DF (January 2015). "The Effects of Stress Exposure on Prefrontal Cortex: Translating Basic Research into Successful Treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder". Neurobiology of Stress. 1: 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.002. PMC 4244027. PMID 25436222.

- ↑ Kozaric-Kovacic D (August 2008). "Psychopharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder". Croatian Medical Journal. 49 (4): 459–475. doi:10.3325/cmj.2008.4.459. PMC 2525822. PMID 18716993.

- ↑ Kaminer D, Seedat S, Stein DJ (June 2005). "Post-traumatic stress disorder in children". World Psychiatry. 4 (2): 121–125. PMC 1414752. PMID 16633528.

- ↑ Jerie P (1980). "Clinical experience with guanfacine in long-term treatment of hypertension. Part II: adverse reactions to guanfacine". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 1): 157S–164S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04924.x. PMC 1430125. PMID 6994770.

- 1 2 3 "Intuniv 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, 4 mg prolonged-release tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. June 2017. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- 1 2 Roth BL, Driscol J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Jasper JR, Lesnick JD, Chang LK, Yamanishi SS, Chang TK, Hsu SA, et al. (April 1998). "Ligand efficacy and potency at recombinant alpha2 adrenergic receptors: agonist-mediated [35S]GTPgammaS binding". Biochemical Pharmacology. 55 (7): 1035–1043. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00631-x. PMID 9605427.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - 1 2 3 Uhlén S, Porter AC, Neubig RR (December 1994). "The novel alpha-2 adrenergic radioligand [3H]-MK912 is alpha-2C selective among human alpha-2A, alpha-2B and alpha-2C adrenoceptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 271 (3): 1558–1565. PMID 7996470.

- ↑ Huang XP, Setola V, Yadav PN, Allen JA, Rogan SC, Hanson BJ, et al. (October 2009). "Parallel functional activity profiling reveals valvulopathogens are potent 5-hydroxytryptamine(2B) receptor agonists: implications for drug safety assessment". Molecular Pharmacology. 76 (4): 710–722. doi:10.1124/mol.109.058057. PMC 2769050. PMID 19570945.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Tardner P (May 2023). "A Comprehensive Literature Review on Guanfacine as a Potential Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)". International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology.

- ↑ van Zwieten PA, Timmermans PB (1983). "Centrally mediated hypotensive activity of B-HT 933 upon infusion via the cat's vertebral artery". Pharmacology. 21 (5): 327–332. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb00311.x. PMC 1427667. PMID 7433512.

- 1 2 3 Arnsten AF (October 2010). "The use of α-2A adrenergic agonists for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 10 (10): 1595–1605. doi:10.1586/ern.10.133. PMC 3143019. PMID 20925474.

- ↑ Wang M, Ramos BP, Paspalas CD, Shu Y, Simen A, Duque A, et al. (April 2007). "Alpha2A-adrenoceptors strengthen working memory networks by inhibiting cAMP-HCN channel signaling in prefrontal cortex". Cell. 129 (2): 397–410. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.015. PMID 17448997. S2CID 741677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ↑ Arnsten AF, Jin LE (March 2012). "Guanfacine for the treatment of cognitive disorders: a century of discoveries at Yale". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 85 (1): 45–58. PMC 3313539. PMID 22461743.

- ↑ Kiechel JR (1980). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of guanfacine in man: a review". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 1): 25S–32S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04901.x. PMC 1430131. PMID 6994775.

- ↑ Kirch W, Köhler H, Braun W (1980). "Elimination of guanfacine in patients with normal and impaired renal function". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 1): 33S–35S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04902.x. PMC 1430110. PMID 6994776.

- ↑ "European Medicines Agency: Intuniv". Europa (web portal). October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "New drugs listed on the PBS for rheumatoid arthritis, cystic fibrosis and ADHD". Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ Connor DF, Grasso DJ, Slivinsky MD, Pearson GS, Banga A (May 2013). "An open-label study of guanfacine extended release for traumatic stress related symptoms in children and adolescents". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 23 (4): 244–251. doi:10.1089/cap.2012.0119. PMC 3657282. PMID 23683139.

- ↑ Belkin MR, Schwartz TL (2015). "Alpha-2 receptor agonists for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder". Drugs in Context. 4: 212286. doi:10.7573/dic.212286. PMC 4544272. PMID 26322115.

- ↑ Srour M, Lespérance P, Richer F, Chouinard S (August 2008). "Psychopharmacology of tic disorders". Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 17 (3): 150–159. PMC 2527768. PMID 18769586.

- ↑ Sofuoglu M, Sewell RA (April 2009). "Norepinephrine and stimulant addiction". Addiction Biology. 14 (2): 119–129. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00138.x. PMC 2657197. PMID 18811678.

- ↑ McKee SA, Potenza MN, Kober H, Sofuoglu M, Arnsten AF, Picciotto MR, et al. (March 2015). "A translational investigation targeting stress-reactivity and prefrontal cognitive control with guanfacine for smoking cessation". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 29 (3): 300–311. doi:10.1177/0269881114562091. PMC 4376109. PMID 25516371.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link)