| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Myrbetriq, Betanis, Betmiga, others |

| Other names | YM-178 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a612038 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 29–35%[4] |

| Protein binding | 71%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver via (direct) glucuronidation, amide hydrolysis, and minimal oxidative metabolism in vivo by CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Some involvement of butylcholinesterase[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 50 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine (55%), faeces (34%)[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.226.392 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

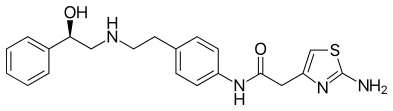

| Formula | C21H24N4O2S |

| Molar mass | 396.51 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Mirabegron, sold under the brand name Myrbetriq among others, is a medication used to treat overactive bladder.[5] Its benefits are similar to antimuscarinic medication such as solifenacin or tolterodine.[6] It is taken by mouth.[5]

Common side effects include high blood pressure, headaches, and urinary tract infections.[5] Other significant side effects include urinary retention, irregular heart rate, and angioedema.[5][7] It works by activating the β3 adrenergic receptor in the bladder, resulting in its relaxation.[5][7]

Mirabegron is the first clinically available beta-3 agonist with approval for use in adults with overactive bladder. Mirabegron was approved for medical use in the United States and in the European Union in 2012.[8][9][3] In 2020, it was the 160th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[10][11] It is available as a generic medication.[12]

In the United Kingdom it is less preferred to antimuscarinic medication such as oxybutynin.[7]

Medical uses

Mirabegron is used is in the treatment of overactive bladder.[13][4][2][1] It works equally well to antimuscarinic medication such as solifenacin or tolterodine.[6][3] In the United Kingdom it is less preferred to these agents.[7]

Mirabegron is also indicated to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO), a bladder dysfunction related to neurological impairment, in children ages three years and older.[13]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects by incidence:[4][2][1]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

Common (1–10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Dry mouth

- Nasopharyngitis

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Headache

- Influenza

- Constipation

- Dizziness

- Joint pain

- Cystitis

- Back pain

- Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI)

- Sinusitis

- Diarrhea

- High heart rate

- Fatigue

- Abdominal pain

- Neoplasms (cancers)

Rare (<1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Palpitations

- Blurred vision

- Glaucoma

- Indigestion

- Gastritis

- Abdominal distension

- Rhinitis

- Elevations in liver enzymes (GGTP, AST, ALT and LDH)

- Renal and urinary disorders (e.g., nephrolithiasis, bladder pain)

- Reproductive system disorders (e.g., vulvovaginal pruritus, vaginal infection)

- Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (e.g., urticaria, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, rash, pruritus, purpura, lip edema)

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome associated with increased serum ALT, AST and bilirubin

- Urinary retention

Research

As a selective beta-3 adrenergic agonist, mirabegron does not cause the cardiovascular adverse effects of other adrenergic agonists that are active at the beta-1 and beta-2 adrenergic receptors. Beta-3 adrenergic agonists activate brown adipose tissue (BAT) and increase energy expenditure, leading to research interest in their development as weight loss drugs.[14] A combination of mirabegron and metformin was studied in mice and caused greater weight loss than either drug alone.[15] A human study in obese individuals found an increase in insulin sensitivity but no significant weight change, which was hypothesized to be due to low levels of BAT in obese humans and/or the low dose of mirabegron used in the study.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 "Betmiga 25mg & 50mg prolonged-release tablets". electronic Medicines Compendium. Astellas Pharma Ltd. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Myrbetriq- mirabegron tablet, film coated, extended release". DailyMed. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Betmiga EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2020. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "mirabegron (Rx) - Myrbetriq". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mirabegron Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- 1 2 "[93] Are claims for newer drugs for overactive bladder warranted?". Therapeutics Initiative. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 763. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Myrbetriq (mirabegron) Extended Release Tablets NDA #202611". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 10 August 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ Sacco E, Bientinesi R, Tienforti D, Racioppi M, Gulino G, D'Agostino D, et al. (April 2014). "Discovery history and clinical development of mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence". Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 9 (4): 433–448. doi:10.1517/17460441.2014.892923. PMID 24559030. S2CID 26424400.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ "Mirabegron - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ "2022 First Generic Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 March 2023. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- 1 2 "FDA Approves New indication for Drug to Treat Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity in Pediatric Patients". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 25 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Hainer V (November 2016). "Beta3-adrenoreceptor agonist mirabegron - a potential antiobesity drug?". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 17 (16): 2125–2127. doi:10.1080/14656566.2016.1233177. PMID 27600952. S2CID 1308773.

- ↑ Zhao XY, Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhao BC, Burley G, Yang ZC, et al. (April 2023). "The combined effect of metformin and mirabegron on diet-induced obesity". MedComm. 4 (2): e207. doi:10.1002/mco2.207. PMC 9928947. PMID 36818016.

- ↑ Dehvari N, Sato M, Bokhari MH, Kalinovich A, Ham S, Gao J, et al. (October 2020). "The metabolic effects of mirabegron are mediated primarily by β3 -adrenoceptors". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 8 (5): e00643. doi:10.1002/prp2.643. PMC 7437350. PMID 32813332.

Further reading

- Sacco E, Bientinesi R (December 2012). "Mirabegron: a review of recent data and its prospects in the management of overactive bladder". Therapeutic Advances in Urology. 4 (6): 315–324. doi:10.1177/1756287212457114. PMC 3491758. PMID 23205058.

- Tyagi P, Tyagi V, Chancellor M (March 2011). "Mirabegron: a safety review". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 10 (2): 287–294. doi:10.1517/14740338.2011.542146. PMID 21142693. S2CID 207487296.

External links

- "Mirabegron". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine.