| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

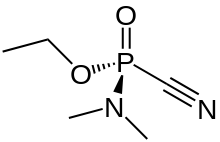

| IUPAC name

(RS)-Ethyl N,N-Dimethylphosphoramidocyanidate | |

| Other names

GA; Ethyl dimethylphosphoramidocyanidate; Dimethylaminoethoxy-cyanophosphine oxide; Dimethylamidoethoxyphosphoryl cyanide; Ethyl dimethylaminocyanophosphonate; Ethyl ester of dimethylphosphoroamidocyanidic acid; Ethyl phosphorodimethylamidocyanidate; Cyanodimethylaminoethoxyphosphine oxide; Dimethylaminoethodycyanophosphine oxide; EA-1205; TL-1578 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H11N2O2P | |

| Molar mass | 162.129 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless to brown liquid |

| Density | 1.0887 g/cm3 at 25 °C 1.102 g/cm3 at 20 °C |

| Melting point | −50 °C (−58 °F; 223 K) |

| Boiling point | 247.5 °C (477.5 °F; 520.6 K) |

| 9.8 g/100 g at 25 °C 7.2 g/100 g at 20 °C | |

| Vapor pressure | 0.07 mmHg (9 Pa) |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Highly toxic. Fires involving this chemical may result in the formation of hydrogen cyanide |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 78 °C (172 °F; 351 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

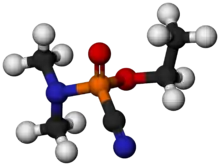

Tabun or GA is an extremely toxic synthetic organophosphorus compound.[1] It is a clear, colorless, and tasteless liquid with a faint fruity odor.[2] It is classified as a nerve agent because it can fatally interfere with normal functioning of the mammalian nervous system. Its production is strictly controlled and stockpiling outlawed by the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993. Tabun is the first of the G-series nerve agents along with GB (sarin), GD (soman) and GF (cyclosarin).

Although pure tabun is clear, less-pure tabun may be brown. It is a volatile chemical, although less so than either sarin or soman.[2]

Tabun can be deactivated chemically using common oxidizing agents such as sodium hypochlorite.[3]

Synthesis

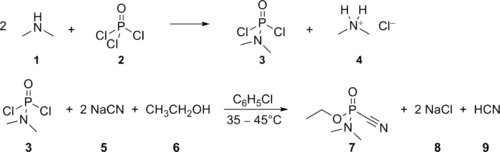

Tabun was made on an industrial scale by Germany during World War II, based on a process developed by Gerhard Schrader. In the chemical agent factory in Dyhernfurth an der Oder, codenamed "Hochwerk", at least 12,000 metric tons of this agent were manufactured between 1942 and 1945. The manufacturing process consisted of two steps, the first being reaction of gaseous dimethylamine (1) with an excess of phosphoryl chloride (2), yielding dimethylamidophosphoric dichloride (3, codenamed "Produkt 39" or "D 4") and dimethylammonium chloride (4). The dimethylamidophosphoric dichloride thus obtained was purified by vacuum distillation and thereafter transferred to the main tabun production line. Here it was reacted with an excess of sodium cyanide (5), dispersed in dry chlorobenzene, yielding the intermediate dimethylamidophosphoric dicyanide (not depicted in the scheme) and sodium chloride (8); then, absolute ethanol (6) was added, reacting with the dimethylamidophosphoric dicyanide to yield tabun (7) and hydrogen cyanide (9). After the reaction, the mixture (consisting of about 75% chlorobenzene and 25% tabun, along with insoluble salts and the rest of the hydrogen cyanide) was filtered to remove the insoluble salts and vacuum-distilled to remove hydrogen cyanide and excess chlorobenzene, so yielding the technical product, consisting either of 95% tabun with 5% chlorobenzene (Tabun A) or (later in the war) of 80% tabun with 20% chlorobenzene (Tabun B).[4]

Effects of exposure

The symptoms of exposure include:[5][6][7] nervousness/restlessness, miosis (contraction of the pupil), rhinorrhea (runny nose), excessive salivation, dyspnea (difficulty in breathing due to bronchoconstriction/secretions), sweating, bradycardia (slow heartbeat), loss of consciousness, convulsions, flaccid paralysis, loss of bladder and bowel control, apnea (breathing stopped) and lung blisters. The symptoms of exposure are similar to those created by all nerve agents. Tabun is toxic even in minute doses. The number and severity of symptoms which appear vary according to the amount of the agent absorbed and rate of entry of it into the body. Very small skin dosages sometimes cause local sweating and tremors accompanied with characteristically constricted pupils with few other effects. Tabun is about half as toxic as sarin by inhalation, but in very low concentrations it is more irritating to the eyes than sarin. Tabun also breaks down slowly, which after repeated exposure can lead to build up in the body.[2]

The effects of tabun appear slowly when tabun is absorbed through the skin rather than inhaled. A victim may absorb a lethal dose quickly, although death may be delayed for one to two hours.[6] A person's clothing can release the toxic chemical for up to 30 minutes after exposure.[2] Inhaled lethal dosages kill in one to ten minutes, and liquid absorbed through the eyes kills almost as quickly. However, people who experience mild to moderate exposure to tabun can recover completely, if treated almost as soon as exposure occurs.[2] The median lethal dose (LD50) for tabun is about 400 mg-min/m3.[8]

The lethal dose for a man is about .01 mg/kg. The median lethal dose for respiration is 400 mg-minute/m3 for humans. Respiratory lethal doses can kill anytime from 1-10 minutes. When the liquid enters the eye, it also can kill just as quickly. When absorbed via the skin, death may occur in 1-2 minutes, or it can take up to 2 hours. [9]

Treatment for suspected tabun poisoning is often three injections of a nerve agent antidote, such as atropine.[7] Pralidoxime chloride (2-PAM Cl) also works as an antidote; however, it must be administered within minutes to a few hours following exposure to be effective.[10]

History

Research into ethyl dialkylaminocyanophosphonate began in the late 19th century, In 1898, Adolph Schall, a graduate student at the University of Rostock under professor August Michaelis, synthesised the diethylamino analog of tabun, as part of his PhD thesis Über die Einwirkung von Phosphoroxybromid auf secundäre aliphatische Amine.[11] However, Schall incorrectly identified the structure of the substance as an imidoether, and Michaelis corrected him in a 1903 article in Liebigs Annalen, Über die organischen Verbindungen des Phosphors mit dem Stickstoff. The high toxicity of the substance (as well as the high toxicity of its precursors, diethylamidophosphoric dichloride and dimethylamidophosphoric dichloride) wasn't noticed at the time, most likely due to the low yield of the synthetic reactions used.

Tabun became the first nerve agent known after a property of this chemical was discovered by pure accident in late December 1936[2][5][12][13][14] by German researcher Gerhard Schrader.[14] Schrader was experimenting with a class of compounds called organophosphates, which kill insects by interrupting their nervous systems, to create a more effective insecticide for IG Farben, a German chemical and pharmaceutical industry conglomerate, at Elberfeld. The substance he discovered, as well as being a potent insecticide, was enormously toxic to humans. It was hence named tabun, a tongue-in-cheek codename to indicate that the substance was 'taboo' (German: tabu) for its intended purpose.

During World War II, as part of the Grün 3 program, a plant for the manufacture of tabun was established at Dyhernfurth (now Brzeg Dolny, Poland), in 1939.[14] Run by Anorgana GmbH, the plant began production of the substance in 1942.[14] The reason for the delay was the extreme precautions used by the plant.[14] Intermediate products of tabun were corrosive, and had to be contained in quartz or silver-lined vessels. Tabun itself was also highly toxic, and final reactions were conducted behind double glass walls.[14] Large scale manufacturing of the agent resulted in problems with tabun's degradation over time, and only around 12,500 tons of material were manufactured before the plant was seized by the Soviet Army. The plant initially produced shells and aerial bombs using a 95:5 mix of tabun and chlorobenzene, designated "Variant A". In the latter half of the war, the plant switched to "Variant B", an 80:20 mix of tabun and chlorobenzene designed for easier dispersion. The Soviets dismantled the plant and shipped it to Russia.

During the Nuremberg Trials, Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments and War Production for the Third Reich, testified that he had planned to kill Adolf Hitler in early 1945 by introducing tabun into the Führerbunker ventilation shaft.[15] He said his efforts were frustrated by the impracticality of tabun and his lack of ready access to a replacement nerve agent,[15] and also by the unexpected construction of a tall chimney that put the air intake out of reach.

The US once considered repurposing captured German stocks of tabun (GA) prior to production of Sarin (GB).[16] Like the other Allied governments, the Soviets soon abandoned tabun (GA) for Sarin (GB) and Soman (GD). Large quantities of the German-manufactured agent were dumped into the sea to neutralize the substance.

Since GA is much easier to produce than the other G-series weapons and the process is comparatively widely understood, countries that develop a nerve agent capability but lack advanced industrial facilities often start by producing GA.

During the Iran–Iraq War of 1980 to 1988, Iraq employed quantities of chemical weapons against Iranian ground forces. Although the most commonly used agents were mustard gas and sarin, tabun and cyclosarin were also used.[7][17]

Tabun was also used in the 1988 Halabja chemical attack.[18]

Producing or stockpiling tabun was banned by the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention. The worldwide stockpiles declared under the convention were 2 tonnes, and as of December 2015 these stockpiles had been destroyed.[19]

See also

- Cyclosarin (GF)

- Deseret Chemical Depot – where the remaining US stockpile was destroyed

- Operation Sandcastle – dumping of World War II German tabun bombs by the UK in 1955–1956

- Francis E. Dec - Schizophrenic and World War II veteran, spoke about the "Tabin Needle" in rants

References

- ↑ PubChem. "Tabun". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Facts About Tabun, National Terror Alert Response System

- ↑ "Sodium Hypochlorite - Medical Countermeasures Database - CHEMM". chemm.hhs.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-25.

- ↑ Lohs, KH: Synthetische Gifte. 3., überarb. u. erg. Aufl., 1967, Deutscher Militärverlag, Berlin (East).

- 1 2 "Nerve Agent: GA". Cbwinfo.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- 1 2 "Chemical Warfare Weapons Fact Sheets — Tabun — GA Nerve Agent". Usmilitary.about.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- 1 2 3 "Tabun | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ "ATSDR — MMG: Nerve Agents: Tabun (GA); Sarin (GB); Soman (GD); and VX". Atsdr.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on April 23, 2003. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ↑ PubChem. "Tabun". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ↑ Emergency Response Safety and Health Database. TABUN (GA): Nerve Agent. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Accessed April 30, 2009.

- ↑ Petroianu, Georg (2014). "Pharmacists Adolf Schall and Ernst Ratzlaff and the synthesis of tabun-like compounds: a brief history". Die Pharmazie. 69 (October 2014): 780–784. doi:10.1691/ph.2014.4028. PMID 25985570.

- ↑ Chemical Warfare Weapons Fact Sheets Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, about.com

- ↑ Chemical Weapons: Nerve Agents, University of Washington

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "A Short History of the Development of Nerve Gases". Noblis.org. Archived from the original on 2011-04-15. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- 1 2 Speer 1970, pp. 430–31.

- ↑ Kitby Nerve Gas army.mil January-June 2020 Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Facts About the Nerve Agent Tabun". ABC News.

- ↑ "1988: Thousands die in Halabja gas attack". March 16, 1988 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (30 November 2016). "Annex 3". Report of the OPCW on the Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction in 2015 (Report). p. 42. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Speer, Albert (1970), Inside the Third Reich, translated by Richard Winston; Clara Winston, New York and Toronto: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-297-00015-0, LCCN 70119132. Republished in paperback in 1997 by Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-684-82949-4

Further reading

- United States Senate, 103d Congress, 2d Session. (May 25, 1994). Material Safety Data Sheet—Lethal Nerve Agent Tabun (GA). Retrieved Nov. 6, 2004.

- United States Central Intelligence Agency (Jul. 15, 1996) Stability of Iraq's Chemical Weapon Stockpile Archived 2011-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Norris, John (1997). NBC: Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Warfare on the Modern Battlefield. Brassey's UK. p. 20. ISBN 1-85753-182-5.