| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.877 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

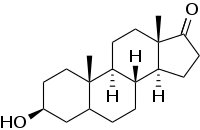

| Formula | C19H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 290.447 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Epiandrosterone, or isoandrosterone,[1][2] also known as 3β-androsterone, 3β-hydroxy-5α-androstan-17-one, or 5α-androstan-3β-ol-17-one, is a steroid hormone with weak androgenic activity. It is a metabolite of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). It was first isolated in 1931, by Adolf Friedrich Johann Butenandt and Kurt Tscherning. They distilled over 17,000 litres of male urine, from which they got 50 milligrams of crystalline androsterone (most likely mixed isomers), which was sufficient to find that the chemical formula was very similar to estrone.

Epiandrosterone has been shown to naturally occur in most mammals including pigs.[3]

Epiandrosterone is naturally produced by the enzyme 5α-reductase from the adrenal hormone DHEA.[4][5][6][7] Epiandrosterone can also be produced from the natural steroids androstanediol via 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase or from androstanedione via 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Yalkowsky SH, He Y, Jain P (19 April 2016). Handbook of Aqueous Solubility Data (Second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 1209–. ISBN 978-1-4398-0246-5.

- ↑ Agarwal OP (2006). Natural Products. Krishna Prakashan Media. pp. 298–. ISBN 978-81-87224-85-3.

- ↑ Raeside JI, Renaud RL, Marshall DE (March 1992). "Identification of 5 alpha-androstane-3 beta,17 beta-diol and 3 beta-hydroxy-5 alpha-androstan-17-one sulfates as quantitatively significant secretory products of porcine Leydig cells and their presence in testicular venous blood". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 42 (1): 113–20. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90017-d. PMID 1558816. S2CID 53274020.

- ↑ Callies F, Arlt W, Siekmann L, Hübler D, Bidlingmaier F, Allolio B (February 2000). "Influence of oral dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on urinary steroid metabolites in males and females". Steroids. 65 (2): 98–102. doi:10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00090-2. PMID 10639021. S2CID 2630118.

- ↑ Labrie F, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Martel C, Bérubé R, Bélanger P, et al. (May 2008). "Changes in serum DHEA and eleven of its metabolites during 12-month percutaneous administration of DHEA". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 110 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.02.003. PMID 18359622. S2CID 24975983.

- ↑ van de Kerkhof DH (2001). Steroid profiling in doping analysis (Ph.D. thesis). University Utrecht. hdl:1874/328.

- ↑ Acacio BD, Stanczyk FZ, Mullin P, Saadat P, Jafarian N, Sokol RZ (March 2004). "Pharmacokinetics of dehydroepiandrosterone and its metabolites after long-term daily oral administration to healthy young men". Fertility and Sterility. 81 (3): 595–604. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.07.035. PMID 15037408.

- ↑ Huang XF, Luu-The V (August 2001). "Gene structure, chromosomal localization and analysis of 3-ketosteroid reductase activity of the human 3(alpha-->beta)-hydroxysteroid epimerase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1520 (2): 124–30. doi:10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00247-0. PMID 11513953.

Further reading

- Simons RG, Grinwich DL (February 1989). "Immunoreactive detection of four mammalian steroids in plants". Canadian Journal of Botany. 67 (2): 288–96. doi:10.1139/b89-042.

- Janeczko A, Skoczowski A (2005). "Mammalian sex hormones in plants". Folia Histochemica et Cytobiologica. 43 (2): 71–9. PMID 16044944.

- Labrie F, Bélanger A, Labrie C, Candas B, Cusan L, Gomez JL (October 2007). "Bioavailability and metabolism of oral and percutaneous dehydroepiandrosterone in postmenopausal women". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 107 (1–2): 57–69. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.02.007. PMID 17627814. S2CID 26410666.

- Uralets VP, Gillette PA (September 1999). "Over-the-counter anabolic steroids 4-androsten-3,17-dione; 4-androsten-3beta,17beta-diol; and 19-nor-4-androsten-3,17-dione: excretion studies in men". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 23 (5): 357–66. doi:10.1093/jat/23.5.357. PMID 10488924.