| Shebitku | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

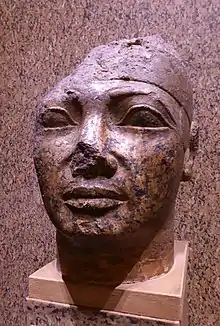

Shebitku's statue in the Nubian Museum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 714–705 BC[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Piye | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Shabaka | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Arty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 705 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 25th Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| šȝ bȝ tȝ kȝ (Shabataka) in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Kushite Monarchs and Rulers |

|---|

|

|

|

Shebitku (Ancient Egyptian: šꜣ-bꜣ-tꜣ-kꜣ, Neo-Assyrian: 𒃻𒉺𒋫𒆪𒀪 šapatakuʾ, Ancient Greek: Σεθῶν Sethōn)[3] also known as Shabataka or Shebitqo, and anglicized as Sethos, was the second pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt who ruled from 714 BC – 705 BC, according to the most recent academic research. He was a son of Piye, the founder of this dynasty. Shebitku's prenomen or throne name, Djedkare, means "Enduring is the Soul of Re."[2] Shebitku's queen was Arty, who was a daughter of king Piye, according to a fragment of statue JE 49157 of the High Priest of Amun Haremakhet, son of Shabaka, found in the temple of the Goddess Mut in Karnak.[4]

Reign before Shabaka

Until recent times, Shebitku was placed within the 25th Dynasty between Shabaka and Taharqa. Although the possibility of a switch between the reigns of Shabaka and Shebitku had already been suggested before by Brunet[5] and Baker had outlined nine reasons for the reversal,[6] it was Michael Bányai in 2013[7] who first published in a mainstream journal many arguments in favor of such a relocation. After him, Frédéric Payraudeau[1] and Gerard P. F. Broekman[8] independently expanded the hypothesis. The archaeological evidence discovered in 2016/2017 by Claus Jurman confirms a Shebitku-Shabaka succession. Gerard Broekman's GM 251 (2017) paper shows that Shebitku reigned before Shabaka since the upper edge of Shabaka’s NLR #30 Year 2 Karnak quay inscription was carved over the left-hand side of the lower edge of Shebitku's NLR#33 Year 3 inscription.[9] The Egyptologist Claus Jurman's personal re-examination of the Karnak quay inscriptions of Shebitku (or Shabataka) and Shabaka in 2016 and 2017 conclusively demonstrate that Shebitku ruled before Shabaka and confirmed Broekman's arguments that Shebitku's Nile Text inscription was carved before Shabaka's inscription; hence, Shebitku ruled before Shabaka.[10] see PDF

Critically, it was first pointed out by Baker[6] and then later by Frederic Payraudeau who wrote in French that "the Divine Adoratrix ie. God's Wife of Amun Shepenupet I," the last Libyan Adoratrix, was still alive during the reign of Shebitku/Shabataqo because she is represented performing rites and is described as “living” in those parts of the Osiris-Héqadjet chapel built during his reign (wall and exterior of the gate)[11][1] In the rest of the room it is Amenirdis I, Shabaka's sister), who is represented with the Adoratrix title and provided with a coronation name. The succession Shepenupet I - Amenirdis I as God's Wife of Amun or Divine Adoratrice of Amun thus took place during the reign of Shebitku. This detail in itself is sufficient to show that the reign of Shabaka cannot precede that of Shebitku.[1]

The construction of the tomb of Shebitku (Ku. 18) resembles that of Piye (Ku. 17) while that of Shabaka (Ku. 15) is similar to that of Taharqa (Nu. 1) and Tantamani (Ku. 16).[12][1] One of the strongest evidence that Shabaka ruled after Shebitku was demonstrated by the architectural features of the Kushite royal pyramids in El Kurru. Only in the pyramids of Piye (Ku 17) and Shebitku (Ku 18) are the burial-chambers open-cut structures with a corbelled roof, whereas fully tunneled burial chamber substructures are found in the pyramids of Shabaka (Ku 15), Taharqa (Nu 1) and Tantamani (Ku 16), as well as with all subsequent royal pyramids in El Kurru and Nuri.[13] The fully tunneled and once-decorated burial chamber of Shabaka's pyramid was clearly an architectural improvement since it was followed by Taharqa and all his successors.[14]

The pyramid design evidence also shows that Shabaka must have ruled after—and not before—Shebitku. This also favours a Shebitku-Shabaka succession in the 25th dynasty. In the Cairo CG 42204 of the High Priest of Amun, Haremakhet—son of Shabaka—calls himself as "king’s son of Shabaka, justified, who loves him, Sole Confidant of king Taharqa, justified, Director of the palace of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Tanutamun/Tantamani, may he live for ever."[15] However, as first noted by Baker,[6] no mention of Haremakhet's service under Shebitku is made; even if Haremakhet was only a youth under Shebitku, this king's absence is strange since the intent of the statue's text was to render a chronological sequence of kings who reigned during Haremakhet's life, each of their names being accompanied by a reference to the relationship that existed between the king mentioned and Haremakhet.[16] A possible explanation for Shebitku's omission from the statue of Haremakhet was that Shebitku was already dead when Haremaket was born under Shabaka.

Payraudeau notes that Shebitku’s shabtis are small (about 10 cm) and have a very brief inscription with only the king's birth name in a cartouche preceded by “the Osiris, king of Upper and Lower Egypt” and followed by mȝʿ-ḫrw.[17][1] They are thus very close to those of Piye/Piankhy [42 – D. Dunham, (see footnote 39), plate 44.]. However, Shabaka's shabtis are larger (about 15–20 cm) with more developed inscriptions, including the quotation from the Book of the Dead, which is also present on those Taharqo, Tanouetamani and Senkamanisken."[1] All this evidence also suggests that Shebitku ruled before Shabaka. Finally, as first pointed out by Baker,[6] and then later by Payraudeau who observed that in the traditional Shebitku-Shabaka chronology, the time span between the reign of Taharqa and Shabaka seems to be excessively long. They both noted that Papyrus Louvre E 3328c from Year 2 or Year 6 of Taharqa mentions the sale of a slave by his owner who had bought him in Year 7 of Shabaka, that is 27 years earlier in the traditional chronology but if the reign of Shabaka is placed just before that of Taharqa (with no intervening reign of Shebitku), there is a gap of about 10 years which is much more credible.[18]

The respected German scholar Karl Jansen Winkeln also endorsed a Shebitku-Shabaka succession in a JEH 10 (2017) N.1 paper titled 'Beiträge zur Geschichte der Dritten Zwischenzeit’, Journal of Egyptian History 10 (2017), pp. 23–42 when he wrote a postscript stating “Im Gegensatz zu meinen Ausführungen auf dem [2014] Kolloquium in Münster bin ich jetzt der Meinung, dass die (neue) Reihenfolge Schebitku—Schabako in der Tat richtig ist...” or ‘In contrast to my exposition at the [2014] Munster colloquium, I am now of the opinion that the (new) succession Shebitku-Shabako is in fact correct…’[19]

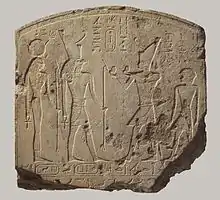

Alleged coregency with Shabaka

The Turin Stela 1467, which depicts Shabaka and Shebitku seated together (with Shebitku behind Shabaka) facing two other individuals across an offering table, was once considered to be clear evidence for a royal co-regency between these two Nubian kings in William J. Murnane's 1977 book on Ancient Egyptian Coregencies.[20] However, the Turin Museum has subsequently acknowledged the statue to be a forgery. Robert Morkot and Stephen Quirke, who analysed the stela in a 2001 article, also confirmed that the object is a forgery which cannot be used to postulate a possible coregency between Shabaka and Shebitku.[21]

Secondly, Shebitku's Year 3, 1st month of Shemu day 5 inscription in Nile Level Text Number 33 has been assumed to record a coregency between Shabaka and Shebitku among some scholars. This Nile text records Shebitku mentioning his appearing (ḫꜥj) in Thebes as king in the temple of Amun at Karnak where "Amun gave him the crown with two uraei like Horus on the throne of Re" thereby legitimising his kingship.[22] Jürgen von Beckerath argued in a GM 136 (1993) article that the inscription recorded both the official coronation of Shebitku and the very first appearance of the king himself in Egypt after comparing this inscription with Nile Level Text No.30 from Year 2 of Shebitku when Shabaka conquered all of Egypt.[23] If correct, this would demonstrate that Shebitku had truly served as a coregent to Shabaka for 2 years.

Kenneth Kitchen, however, observes that the "verb ḫꜥj (or appearance) applies to any official 'epiphany' or official manifestation of the king to his 'public appearances'."[24] Kitchen also stresses that the period around the first month of Shemu days 1-5 marked the date of a Festival of Amun-Re at Karnak which is well attested during the New Kingdom Period, the 22nd Dynasty and through to the Ptolemaic period.[24] Hence, in the third Year of Shebitku, this Feast to Amun evidently coincided with both the Inundation of the Nile and a personal visit by Shebitku to the Temple of Amun "but we have no warrant whatever for assuming that Shebitku...remained uncrowned for 2 whole years after his accession."[25] William Murnane also endorsed this interpretation by noting that Shebitku's Year 3 Nile Text "need not refer to an accession or coronation at all. Rather, it seems simply to record an 'appearance' of Shebitku in the temple of Amun during his third year and to acknowledge the god's influence in securing his initial appearance as king."[26] In other words, Shebitku was already king of Egypt and the purpose of his visit to Karnak was to receive and record for posterity the god Amun's official legitimization of his reign. Therefore, the evidence for a possible coregency between Shabaka and Shebitku is illusory at present.

Dan'el Kahn also carefully considered but rejected arguments against a division of the 25th dynasty kingdom under Shabaka's reign with Shabaka ruling in Lower and Upper Egypt and Shebitku, acting as Shabaka's junior coregent or viceroy, in Nubia in an important 2006 article.[27] Kahn notes that there was always only one Nubian king ruling over all of the 25th dynasty's domain including both Egypt and Nubia and that problems of communication and control "did not hinder the kushite king to be the supreme ruler of this vast territory."[28] Kahn stresses that the Great Triumphal stela of Piye indicates it took only 39 days to travel by boat from Napata to Thebes while the Nitocris Adoption Stela shows that "the time to travel the distance between Memphis (or possibly Tanis) and Thebes by boat (c.700 km or more for Tanis) is [only] 16 days."[29]

Timeline

In 1999, an Egypt-Assyrian synchronism from the Great Inscription of Tang-i Var in Iran was re-discovered and re-analysed. Carved by Sargon II of Assyria (722-705 BC), the inscription dates to the period around 707/706 BC and reveals that it was Shebitku, king of Egypt, who extradited the rebel king Iamani of Ashdod into Sargon's hands, rather than Shabaka as previously thought.[30] The pertinent section of the inscription by Sargon II reads:

(19) I (scil. Sargon) plundered the city of Ashdod, Iamani,[31] its king, feared [my weapons] and...He fled to the region of the land of Meluhha and lived (there) stealthfully (literally:like a thief). (20) Shapataku' (Shebitku) king of the land of Meluhha, heard of the mig[ht] of the gods Ashur, Nabu (and) Marduk which I had [demonstrated] over all lands...(21) He put (Iamani) in manacles and handcuffs...he had him brought captive into my presence.[32]

It was noted by Kenneth Kitchen that the Assyrian term used "sharru" was not exclusively used to mean king but rather various levels of officials. He also contended that Meluha referred to Nubia (Kush). This supported Kitchen's contention that Shebitku was a deputy ruler for Shabaka, in Nubia, at that time. The net result was to move the 12 year reign of Shebitku to 702 BC and following.[33]

The Tang-i Var inscription dates to Sargon's 15th year between Nisan 707 BC to Adar 706 BC.[34] This shows that Shebitku was ruling in Egypt by April 706 BC at the very latest, and perhaps as early as November 707 BC to allow some time for Iamanni's extradition and the recording of this deed in Sargon's inscription.[35] A suggestion that Shebitku served as Shabaka's viceroy in Nubia and that Shebitku extradited Iamanni to Sargon II during the reign of king Shabaka has been rejected by the Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln in Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies), which is the most updated publication on Egyptian chronology.[36] As Jansen-Winkeln writes:

- there has never been the slightest hint at any form of coregency of the Nubian kings of Dynasty 25. Had Shabaka been ruler of Egypt in the year 707/706 and Shebitku [was] his "viceroy" in Nubia, one would definitely expect that the opening of diplomatic relations with Assur as well as the capture and extradation of Yamanni would have been part of Shabaka's responsibility. Sargon can also be expected to have named the regent of Egypt and senior king, rather than the distant viceroy Shebitku [in Nubia]. If, on the other hand, Shebitku was already Shabaka's successor in 707/706 [BC], the reports of the Yamani affair become clearer and make more sense. It had hitherto been assumed that the Nubian king (Shabaka) handed over Yamani more or less immediately after his flight to Egypt. Now it appears...certain that Yamani was only turned over to the Assyrians a couple of years later (under Shebitku instead).[36]

Identification with Herodotus' Sethos

The Greek historian Herodotus in his Histories (book II, chapter 141) writes of a High Priest of Ptah named Sethos (Greek: Σεθῶν Sethon) who became pharaoh and defeated the Assyrians with divine intervention. This name is probably a corruption of Shebitku.[37][38] Herodotus' account was the inspiration for the 18th-century fantasy novel Life of Sethos, which has been influential among Afrocentrists.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 F. Payraudeau, Retour sur la succession Shabaqo-Shabataqo, Nehet 1, 2014, p. 115-127 online here

- 1 2 Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p.190. 2006. ISBN 0-500-28628-0

- ↑ "Šapatakuʾ [KING OF MELUHHA] (RN)". Oracc: The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus.

- ↑ Karl Jansen-Winkeln, Inschriften der Spätzeit: Teil III: Die 25. Dynastie, 2009. pp.347-8 [52.5]

- ↑ Jean-Frédéric Brunet, “The 21st and 25th Dynasties Apis Burial Conundrum”, Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 10 (2005), p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 Joe Baker (2005), on egyptologyforum.org

- ↑ Michael Bányai, “Ein Vorschlag zur Chronologie der 25. Dynastie in Ägypten”, JEgH 6 (2013) 46-129 and forthcoming “Die Reihenfolge der kuschitischen Könige”, JEgH 8 (2015) 81-147

- ↑ Gerard P. F. Broekman, “The order of succession between Shabaka and Shabataka; A different view on the chronology of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty”, GM 245 (2015) 17-31.

- ↑ G.P.F. Broekman, Genealogical considerations regarding the kings of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty in Egypt, GM 251 (2017), p.13

- ↑ Claus Jurman, The Order of the Kushite Kings According to Sources from the Eastern Desert and Thebes. Or: Shabataka was here first!, Journal of Egyptian History 10 (2017), pp.124-151

- ↑ [45 – G. Legrain, “Le temple et les chapelles d’Osiris à Karnak. Le temple d’Osiris-Hiq-Djeto, partie éthiopienne”, RecTrav 22 (1900) 128; JWIS III, 45.]

- ↑ [39 – D. Dunham, El-Kurru, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, I, (1950) 55, 60, 64, 67; also D. Dunham, Nuri, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, II, (1955) 6-7; J. Lull, Las tumbas reales egipcias del Tercer Periodo Intermedio (dinastías XXI-XXV). Tradición y cambios, BAR-IS 1045 (2002) 208.].

- ↑ Dows D. Dunham, El Kurru; The Royal Cemeteries of Kush (Cambridge, Massachusetts 1950)

- ↑ G.P.F. Broekman, The order of succession between Shabaka and Shabataka. A different view on the chronology of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, GM 245, (2015), pp.21-22

- ↑ G.P.F. Broekman, The order of succession between Shabaka and Shabataka. A different view on the chronology of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, GM 245, (2015), p.23

- ↑ G.P.F. Broekman, GM 245 (2015), p.24

- ↑ [41 – JWIS III, 51, number 9; D. Dunham, (see footnote 39), 69, plate 45A-B.].

- ↑ Payraudeau, Nehet I, 2014, p.119

- ↑ Jansen-Winkeln, Journal of Egyptian History 10 (2017), N1, p.40

- ↑ William Murnane, Ancient Egyptian Coregencies, (SAOC 40: Chicago 1977), p.190

- ↑ R. Morkot and S. Quirke, "Inventing the 25th Dynasty: Turin stela 1467 and the construction of history", Begegnungen — Antike Kulturen im Niltal Festgabe für Erika Endesfelder, Karl-Heinz Priese, Walter Friedrich Reineke, Steffen Wenig (Leipzig 2001), pp.349–363

- ↑ L. Török, The Royal Crowns of Kush: A Study in Middle Nile Valley Regalia and Iconography in the 1st Millennia B. C. and A.D., Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 18 (Oxford 1987), p.4

- ↑ J. von Beckerath, "Die Nilstandsinschrift vom 3. Jahr Schebitkus am kai von Karnak," GM 136 (1993), pp. 7-9

- 1 2 Kenneth A. Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC) [TIPE], 3rd edition, 1986, Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd, p.170

- ↑ Kitchen, TIPE, p.171

- ↑ Murnane, Coregencies, p.189

- ↑ Kahn, Dan'el., Divided Kingdom, Co-regency, or Sole Rule in the Kingdom(s) of Egypt-and-Kush?, Egypt and Levant 16 (2006), pp.275-291 online PDF

- ↑ Kahn, Egypt and Levant 16, p.290

- ↑ Kahn, Egypt and Levant 16, p.290 Kahn cites RA Caminos, The Nitocris Stela, JEA 50 (1964), pp.81-84 for the Nitocris stela evidence

- ↑ Grant Frame, "The Inscription of Sargon II at Tang-i Var," Orientalia Vol.68 (1999), pp.31-57 and pls. I-XVIII

- ↑ Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008:30, makes a case for Iamani to be simply "the Ionian Greek": "Ionian Greeks were sometimes written in cuneiform script as ia-am-na-a: could this usurping Iamani be a Greek? ...would Assyrian scribes be exact about the name of a lowly rebel?"

- ↑ Frame, p.40

- ↑ Kitchen, Kenneth A., "THE STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF EGYPTIAN CHRONOLOGY — A RECONSIDERATION", Ägypten Und Levante / Egypt and the Levant, vol. 16, pp. 293–308, 2006

- ↑ A. Fuchs, Die Inschriften Sargons II. aus Khorsabad (Gottingen 1994) pp.76 & 308

- ↑ Kahn, p.3

- 1 2 Karl Jansen-Winkeln, "The Third Intermediate Period" in Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss & David Warburton (editors), Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies), Brill, 2006. pp.258-259

- ↑ Robert B. Strassler (ed.), The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories (Anchor, 2007), p. 182

- ↑ Alan B. Lloyd, Commentary on Book II, in A Commentary on Herodotus, Books I–IV (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 237.

Further reading

- Robert Morkot, The Black Pharaohs: Egypt's Nubian Rulers, The Rubicon Press, 2000. ISBN 0-948695-23-4