| Neferkauhor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neferkawhor, Chuwihapi, Chui[...](?), Khuihapy, Ka(?)puib(i)(?) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cartouche of Neferkauhor on the Abydos King List. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2 years, 1 month and 1 day | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Neferkaure II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Neferirkare | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Nebet (Nebyet), married to Shemay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Eighth Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neferkauhor Khuwihapi was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Eighth Dynasty during the early First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BC), at a time when Egypt was possibly divided between several polities. Neferkauhor was the sixteenth and penultimate[3] king of the Eighth Dynasty and as such would have ruled over the Memphite region.[4][5] Neferkauhor reigned for little over 2 years[6] and is one of the best attested kings of this period with eight of his decrees surviving in fragmentary condition to this day.[7]

Attestations on king lists

Neferkauhor is listed on entry 55 of the Abydos King List, a king list redacted during the reign of Seti I, some 900 years after Neferkauhor's lifetime.[5] He is believed to have been listed on the Turin Canon as well even though his name is lost in a lacuna affecting column 5, row 12 of the document (following Kim Ryholt's reconstruction).[5][6] The duration of his reign is, however, preserved and given as "2 years, 1 month and 1 day".[6]

The decrees of Neferkauhor

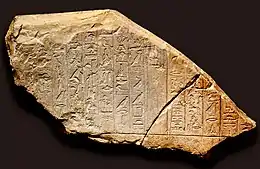

A total of eight[5] different decrees found in the temple of Min at Coptos are attributed to Neferkauhor and survive to this day in fragmentary condition.[8] Four of these decrees, inscribed on limestone slabs, were given in 1914 by the philanthropist Edward Harkness to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where there are now on display in Gallery 103.[9]

Seven out of the eight decrees were issued on a single day[5] of the first year of reign of Neferkauhor, perhaps on the day of his accession to the throne.[7] The year in question is given the name of "Year of Uniting the Two Lands". In the first decree Neferkauhor bestows titles to his eldest daughter Nebyet, wife of a vizier named Shemay. He attributes her a bodyguard, the commandant of soldiers Khrod-ny (also read Kha’redni[10]), and orders the construction of a sacred barque for a god called "Two-Powers", perhaps the syncretized god Horus-Min.[7][10]

The second and best preserved of the decrees concerns the appointment of Shemay's son, Idy, to the post of governor of Upper Egypt, ruling over the seven southernmost nomes from Elephantine to Diospolis Parva:[1][7]

The Horus Netjerbau. Sealed in the presence of the king himself in the Month 2 [of Peret, Day 20]. Royal decree to the count, the over[seer of priests, Idy]: you are appointed count, governor of Upper Egypt, overseer of priests in this same Upper Egypt, which [is under] your supervision southward to Nubia, northward to the Sistrum nome, functioning as count, overseer of priests, chief of the rulers of towns who are under your supervision, in place of your father, the father of the god, beloved of the god, the hereditary prince, mayor of the [pyramid ci]ty, chief justice, vizier, keeper of the king's archives, [count, governor of Upper Egypt, overseer of priests, Shemay. No] one [shall have rightfull claim against it]...

The third and fourth decrees are partially preserved on a single fragment. They record Neferkauhor giving Idy's brother a post in the temple of Min and possibly also informing Idy about it.[7] This last decree records why the decrees were found in the temple of Min:[1][7]

[My majesty commands you to post] the words [of this decree at the gate]way of the temple of Min [of Coptos forever] and ever. There is sent the sole companion, Hemy's son, Intef, concerning it. Sealed in the presence of the [king] himself in the Year of Uniting the Two Lands, Month 2 of Peret, Day 20."

The remaining decrees concern the appointment of mortuary priests to the chapels of Nebyet and Shemay as well as ordering inventories at the temple of Min.[5]

Other attestations

Beyond the decrees Neferkauhor is also attested by two inscriptions on a wall in Shemay's tomb. They are dated to the first year of his reign, Month 4 of Shemu, Day 2.[11] The inscriptions report the bringing of stone from the Wadi Hammamat (Coptos is the starting point for expeditions to this Wadi). The inscriptions are partly destroyed, but seem to mention that the work was done within 19 days. From the Wadi Hammamat are known three rock inscriptions reporting the bringing of a stone. One of the texts is dated under year one of an unnamed king. In two of the inscriptions an Idy is also mentioned. If this Idy is identical to the one known from the decrees, the inscriptions also refer to this expedition under the king.[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Kurt Sethe: Urkunden des Alten Reichs (= Urkunden des ägyptischen Altertums. Abteilung 1). 1. Band, 4. Heft. 2., augmented edition, Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1933, see p. 297-299, available online.

- ↑ Translation after Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen, Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3, p. 175.

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: The Date of the End of the Old Kingdom, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 21 (1962), p.143

- ↑ Jürgen von Beckerath: Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen, Münchner ägyptologische Studien, Heft 49, Mainz : P. von Zabern, 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2591-6, available online Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine see p. 68

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I - Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300–1069 BC, Stacey International, ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9, 2008, p. 271-272

- 1 2 3 Kim Ryholt: "The Late Old Kingdom in the Turin King-list and the Identity of Nitocris", Zeitschrift für ägyptische, 127, 2000, p. 99

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 William C. Hayes: The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom , MetPublications, 1978, pp.136-138, available online

- ↑ William C. Hayes: Royal Decrees from the Temple of Min at Coptos, JEA 32(1946), pp. 3–23.

- ↑ The fragments of the decrees on the catalog of the MET: fragment 1, 2 and 3.

- 1 2 Margaret Bunson: Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1438109978, available online, see p. 268 and p. 284 for Kha’redni.

- ↑ Nigel C. Strudwick, :Texts from the Pyramid Age, Writings from the Ancient World, Ronald J. Leprohon (ed.), Society of Biblical Literature 2005, ISBN 978-1589831384, available online, see pp.345-347

- ↑ Maha Farid Mostafa: The Mastaba of SmAj at Naga' Kom el-Koffar, Qift, Vol. I, Cairo 2014, ISBN 978-977642004-5, p. 88-111