| Amasis II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmose II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Head of Amasis II, c. 550 BCE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 570–526 BCE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Apries | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Psamtik III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Tentkheta, mother of Psamtik III Nakhtubasterau Ladice Khedebneithirbinet II? (daughter of Apries) Tadiasir? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Psamtik III Pasenenkhonsu Ahmose (D) Tashereniset II ? Nitocris II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Tashereniset I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 526 B.C.E. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Temple of Neith at Sais | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 26th dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amasis II (Ancient Greek: Ἄμασις Ámasis; Phoenician: 𐤇𐤌𐤎 ḤMS)[2] or Ahmose II was a pharaoh (reigned 570 – 526 BCE) of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the successor of Apries at Sais. He was the last great ruler of Egypt before the Persian conquest.[3]

Life

Most of our information about him is derived from Herodotus (2.161ff) and can only be imperfectly verified by monumental evidence. According to the Greek historian, he was of common origins.[4] He was originally an officer in the Egyptian army. His birthplace was Siuph at Saïs. He took part in a general campaign of Pharaoh Psamtik II in 592 BC in Nubia.[5]

A revolt which broke out among native Egyptian soldiers gave him his opportunity to seize the throne. These troops, returning home from a disastrous military expedition to Cyrene in Libya, suspected that they had been betrayed in order that Apries, the reigning king, might rule more absolutely by means of his Greek mercenaries; many Egyptians fully sympathized with them. General Amasis, sent to meet them and quell the revolt, was proclaimed king by the rebels instead, and Apries, who then had to rely entirely on his mercenaries, was defeated.[6] Apries fled to the Babylonians and was captured and killed mounting an invasion of his native homeland in 567 BCE with the aid of a Babylonian army.[7] An inscription confirms the struggle between the native Egyptian and the foreign soldiery, and proves that Apries was killed and honourably buried in the third year of Amasis (c. 567 BCE).[6] Amasis then married Khedebneithirbinet II, one of the daughters of his predecessor Apries, in order to legitimise his kingship.[8]

Some information is known about the family origins of Amasis: his mother was a certain Tashereniset, as a bust of her, today located in the British Museum, shows.[9] A stone block from Mehallet el-Kubra also establishes that his maternal grandmother—Tashereniset's mother—was a certain Tjenmutetj.[9]

His court is relatively well known. The head of the gate guard Ahmose-sa-Neith appears on numerous monuments, including the location of his sarcophagus. He was referenced on monuments of the 30th Dynasty and apparently had a special significance in his time. Wahibre was 'Leader of the southern foreigners' and 'Head of the doors of foreigners', so he was the highest official for border security. Under Amasis the career of the doctor, Udjahorresnet, began, who was of particular importance to the Persians. Several "heads of the fleet" are known. Psamtek Meryneit and Pasherientaihet / Padineith are the only known viziers.

Herodotus describes how Amasis II would eventually cause a confrontation with the Persian armies. According to Herodotus, Amasis was asked by Cambyses II or Cyrus the Great for an Egyptian ophthalmologist on good terms. Amasis seems to have complied by forcing an Egyptian physician into mandatory labor, causing him to leave his family behind in Egypt and move to Persia in forced exile. In an attempt to exact revenge for this, the physician grew very close to Cambyses and suggested that Cambyses should ask Amasis for a daughter in marriage in order to solidify his bonds with the Egyptians. Cambyses complied and requested a daughter of Amasis for marriage.[10]

Amasis, worrying that his daughter would be a concubine to the Persian king, refused to give up his offspring; Amasis also was not willing to take on the Persian empire, so he concocted a deception in which he forced the daughter of the ex-pharaoh Apries, whom Herodotus explicitly confirms to have been killed by Amasis, to go to Persia instead of his own offspring.[10][11][12]

This daughter of Apries was none other than Nitetis, who was, as per Herodotus's account, "tall and beautiful." Nitetis naturally betrayed Amasis and upon being greeted by the Persian king explained Amasis's trickery and her true origins. This infuriated Cambyses and he vowed to take revenge for it. Amasis died before Cambyses reached him, but his heir and son Psamtik III was defeated by the Persians.[10][12]

Herodotus also describes how, just like his predecessor, Amasis relied on Greek mercenaries and councilmen. One such figure was Phanes of Halicarnassus, who would later leave Amasis, for reasons that Herodotus does not clearly know, but suspects were personal between the two figures. Amasis sent one of his eunuchs to capture Phanes, but the eunuch was bested by the wise councilman and Phanes fled to Persia, meeting up with Cambyses and providing advice for his invasion of Egypt. Egypt was finally lost to the Persians during the battle of Pelusium in 525 BC.[12]

Egypt's wealth

Amasis brought Egypt into closer contact with Greece than ever before. Herodotus relates that under his prudent administration, Egypt reached a new level of wealth; Amasis adorned the temples of Lower Egypt especially with splendid monolithic shrines and other monuments (his activity here is proved by existing remains).[6] For example, a temple built by him was excavated at Tell Nebesha.

Amasis assigned the commercial colony of Naucratis on the Canopic branch of the Nile to the Greeks, and when the temple of Delphi was burnt, he contributed 1,000 talents to the rebuilding. He also married a Greek princess named Ladice daughter of King Battus III and made alliances with Polycrates of Samos and Croesus of Lydia.[6] Montaigne cites the story by Herodotus that Ladice cured Amasis of his impotence by praying to Venus/Aphropdite.[13]

Under Amasis, Egypt's agricultural based economy reached its zenith. Herodotus, who visited Egypt less than a century after Amasis II's death, writes that:

It is said that it was during the reign of Ahmose II (Amasis) that Egypt attained its highest level of prosperity both in respect of what the river gave the land and in respect of what the land yielded to men and that the number of inhabited cities at that time reached in total 20,000.[14]

His kingdom consisted probably of Egypt only, as far as the First Cataract, but to this he added Cyprus, and his influence was great in Cyrene, Libya.[6] In his fourth year (c. 567 BCE), Amasis's kingdom was invaded by the Babylonians, under the leadership of Nebuchadnezzar II.[15] He repelled subsequent invasions, forcing Nebuchadnezzar II to retire plans to conquer his kingdom.[16] However, Amasis was later faced with a more formidable enemy with the rise of Persia under Cyrus who ascended to the throne in 559 BCE; his final years were preoccupied by the threat of the impending Persian onslaught against Egypt.[17] With great strategic skill, Cyrus had destroyed Lydia in 546 BCE and finally defeated the Babylonians in 538 BCE which left Amasis with no major Near Eastern allies to counter Persia's increasing military might.[17] Amasis reacted by cultivating closer ties with the Greek states to counter the future Persian invasion into Egypt but died in 526 BCE shortly before the Persians attacked.[17] The final assault instead fell upon his son Psamtik III, whom the Persians defeated in 525 BCE after he had reigned for only six months.[18]

Tomb and desecration

Amasis II died in 526 BC. He was buried at the royal necropolis of Sais within the temple enclosure of Neith, and while his tomb has not been rediscovered, Herodotus describes it for us:

[It is] a great cloistered building of stone, decorated with pillars carved in the imitation of palm-trees, and other costly ornaments. Within the cloister is a chamber with double doors, and behind the doors stands the sepulchre.[19]

Herodotus also relates the desecration of Amasis' mummy when the Persian king Cambyses conquered Egypt and thus ended the 26th (Saite) Dynasty:

No sooner did [Cambyses] enter the palace of Amasis that he gave orders for his [Amasis's] body to be taken from the tomb where it lay. This done, he proceeded to have it treated with every possible indignity, such as beating it with whips, sticking it with goads, and plucking its hairs... As the body had been embalmed and would not fall to pieces under the blows, Cambyses had it burned.[20]

Later reputation

From the fifth century BCE, there is evidence of stories circulating about Amasis, in Egyptian sources (including a demotic papyrus of the third century BCE), Herodotus, Hellanikos, and Plutarch's Convivium Septem Sapientium. 'In those tales Amasis was presented as a non-conventional Pharaoh, behaving in ways unbecoming to a king but gifted with practical wisdom and cunning, a trickster on the throne or a kind of comic Egyptian Solomon'.[21]

Gallery of images

Relief showing Amasis from the Karnak temple

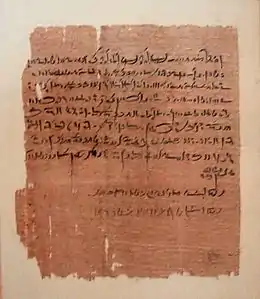

Relief showing Amasis from the Karnak temple Papyrus, written in demotic script in the 35th year of Amasis II, on display at the Louvre

Papyrus, written in demotic script in the 35th year of Amasis II, on display at the Louvre Grant of a parcel of land by an individual to a temple. Dated to the first year of Amasis II, on display at the Louvre

Grant of a parcel of land by an individual to a temple. Dated to the first year of Amasis II, on display at the Louvre A stele dating to the 23rd regnal year of Amasis, on display at the Louvre

A stele dating to the 23rd regnal year of Amasis, on display at the Louvre

References

- 1 2 Peter A. Clayton (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-By-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-500-28628-9.

- ↑ Schmitz, Philip C.. "Chapter 3. Three Phoenician "Graffiti" at Abu Simbel (CIS I 112)". The Phoenician Diaspora: Epigraphic and Historical Studies, University Park, US: Penn State University Press, 2021, pp. 35-39. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781575066851-005

- ↑ Lloyd, Alan Brian (1996), "Amasis", in Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Anthony (eds.), Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-521693-8

- ↑ Mason, Charles Peter (1867). "Amasis (II)". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt (Paperback ed.). Thames & Hudson. pp. 195–197. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1911). "Amasis s.v. Amasis II.". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 782. This cites:

- W. M. Flinders Petrie, History, vol. iii.

- James Henry Breasted, History and Historical Documents, vol. iv. p. 509

- Gaston Maspero, Les Empires.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, Book II, Chapter 169

- ↑ "Amasis". Livius. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- 1 2 Dodson, Aidan & Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 245 & 247. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- 1 2 3 Herodotus (1737). The History of Herodotus Volume I,Book II. D. Midwinter. pp. 246–250.

- ↑ Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1837). Manners and customs of the ancient Egyptians: including their private life, government, laws, art, manufactures, religions, and early history; derived from a comparison of the paintings, sculptures, and monuments still existing, with the accounts of ancient authors. Illustrated by drawings of those subjects, Volume 1. J. Murray. p. 195.

- 1 2 3 Herodotus (Trans.) Robin Waterfield, Carolyn Dewald (1998). The Histories. Oxford University Press, US. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-19-158955-3.

- ↑ Montaigne, de, Michel. "20". In William Carew Hazlitt (ed.). The Essays of Michel de Montaigne. Translated by Charles Cotton. The University of Adelaide. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ↑ Herodotus, (II, 177, 1)

- ↑ Ephʿal, Israel (2003). "Nebuchadnezzar the Warrior: Remarks on his Military Achievements". Israel Exploration Journal. 53 (2): 187–188. JSTOR 27927044.

- ↑ Lloyd, Alan B. (2002). "The Late Period". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Paperback ed.). Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 381–82. ISBN 0-19-280293-3.

- 1 2 3 Lloyd. (2002) p.382

- ↑ Griffith 1911.

- ↑ KAWAI, Nozomu (1998). "ROYAL TOMBS OF THE THIRD INTERMEDIATE AND LATE PERIODS". Orient. 33: 33–45. doi:10.5356/orient1960.33.33. ISSN 1884-1392.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, Book III, Chapter 16

- ↑ Konstantakos, Ioannis M. (2004). "Trial by Riddle: The Testing of the Counsellor and the Contest of Kings in the Legend of Amasis and Bias". Classica et Mediaevalia. 55: 85–137 (p. 90).

Further reading

- Ray, John D. (1996). "Amasis, the pharaoh with no illusions". History Today. 46 (3): 27–31.

- Leo Depuydt: Saite and Persian Egypt, 664 BC–332 BC (Dyns. 26–31, Psammetichus I to Alexander's Conquest of Egypt). In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (Hrsg.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Band 83). Brill, Leiden/Boston 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5, S. 265–283 (Online).