| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Truxal, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | Typical antipsychotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 8–12 hours |

| Excretion | Feces, urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.666 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

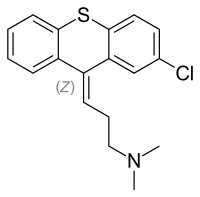

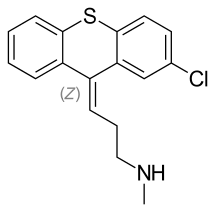

| Formula | C18H18ClNS |

| Molar mass | 315.86 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Chlorprothixene, sold under the brand name Truxal among others, is a typical antipsychotic of the thioxanthene group.

Medical uses

Chlorprothixene's principal indications are the treatment of psychotic disorders (e.g. schizophrenia) and of acute mania occurring as part of bipolar disorders.

Other uses are pre- and postoperative states with anxiety and insomnia, severe nausea / emesis (in hospitalized patients), the amelioration of anxiety and agitation due to use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression and, off-label, the amelioration of alcohol and opioid withdrawal. It may also be used cautiously to treat nonpsychotic irritability, aggression, and insomnia in pediatric patients.

An intrinsic antidepressant effect of chlorprothixene has been discussed, but not proven. Likewise, it is unclear if chlorprothixene has genuine (intrinsic) analgesic effects. However, chlorprothixene can be used as co-medication in severe chronic pain. Also, like most antipsychotics, chlorprothixene has antiemetic effects.

Side effects

Chlorprothixene has a strong sedative activity with a high incidence of anticholinergic side effects. The types of side effects encountered (dry mouth, massive hypotension and tachycardia, hyperhidrosis, substantial weight gain etc.) normally do not allow a full effective dose for the remission of psychotic disorders to be given. So cotreatment with another, more potent, antipsychotic agent is needed.

Chlorprothixene is structurally related to chlorpromazine, with which it shares, in principle, all side effects. Allergic side effects and liver damage seem to appear with an appreciable lower frequency. The elderly are particularly sensitive to anticholinergic side effects of chlorprothixene (precipitation of narrow angle glaucoma, severe obstipation, difficulties in urinating, confusional and delirant states). In patients >60 years the doses should be particularly low.

Early and late extrapyramidal side effects may occur but have been noted with a low frequency (one study with a great number of participants has delivered a total number of only 1%).

Overdose

Overdose symptoms can be confusion, hypotension, and tachycardia, and several fatalities have been reported with concentrations in postmortem blood ranging from 0.1 to 7.0 mg/L compared to non-toxic levels in postmortem blood which can extend to 0.4 mg/kg.[2]

Interactions

Chlorprothixene may increase the plasma-level of concomitantly given lithium. In order to avoid lithium intoxication, lithium plasma levels should be monitored closely.

If chlorprothixene is given concomitantly with opioids, the opioid dose should be reduced (by approx. 50%), because chlorprothixene amplifies the therapeutic actions and side effects of opioids considerably.

Avoid the concomitant use of chlorprothixene and tramadol (Ultram). Seizures may be encountered with this combination.

Consider additive sedative effects and confusional states to emerge, if chlorprothixene is given with benzodiazepines or barbiturates. Choose particular low doses of these drugs.

Exert particular caution in combining chlorprothixene with other anticholinergic drugs (tricyclic antidepressants and antiparkinsonian agents): Particularly the elderly may develop delirium, high fever, severe obstipation, even ileus and glaucoma .

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 110 | ND | [4] |

| NET | 21–532 | Human | [4][5] |

| DAT | 1,699 | ND | [4] |

| 5-HT1A | 138–230 | Human | [6][4] |

| 5-HT2A | 0.30–0.43 | Human | [6][4] |

| 5-HT2B | ND | ND | ND |

| 5-HT2C | 4.5 | ND | [4] |

| 5-HT3 | 398 | ND | [4] |

| 5-HT6 | 3.0–3.2 | Rat | [4][7][8] |

| 5-HT7 | 5.0–5.6 | Rat | [4][7][8] |

| α1 | 1.0 | ND | [4] |

| α2 | 186 | ND | [4] |

| β | >10,000 | Mammal | [9] |

| D1 | 12–18 | Human | [10][4] |

| D2 | 3.0–5.6 | Human | [10][11][4] |

| D3 | 1.9–4.6 | Human | [4][10] |

| D4 | 0.65 | Human | [11][4] |

| D5 | 9.0 | Human | [10] |

| H1 | 0.89–3.8 | Human | [4][10] |

| H3 | >1,000 | Human | [10] |

| mACh | 41 | ND | [4] |

| M1 | 11–26 | Human | [12][4] |

| M2 | 28–79 | Human | [12][4] |

| M3 | 22 | Human | [12][4] |

| M4 | 18 | Human | [12] |

| M5 | 25 | Human | [12] |

| σ | 603 | ND | [4] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Chlorprothixene is an antagonist of the following receptors:

- 5-HT2, 5-HT6, 5-HT7: antipsychotic effects, sedation/anxiolysis, antidepressant effect, weight gain

- D1, D2, D3, D4, D5: antipsychotic effects, sedation, extrapyramidal side effects, prolactin increase, depression, apathy/anhedonia, weight gain

- H1: sedation, weight gain

- Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: anticholinergic effects, inhibition of extrapyramidal side effects

- α1-Adrenergic: hypotension, sedation, anxiolysis

Because of its potent serotonin 5-HT2A and muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonism, chlorprothixene causes relatively mild extrapyramidal symptoms.[13] This is in contrast to most other typical antipsychotics.[13] For this reason, chlorprothixene has sometimes been described instead as an atypical antipsychotic.[13]

Chlorprothixene has also been found to act as FIASMA (functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase).[14]

Pharmacokinetics

One metabolite of chlorprothixene is N-desmethylchlorprothixene.

History

Chlorprothixene was the first of the thioxanthene antipsychotics to be synthesized.[15] It was introduced in 1959 by Lundbeck.[16]

Lometraline, tametraline, and sertraline were reportedly derived via structural modification of chlorprothixene.

Society and culture

Brand names

Chlorprothixene is sold mainly under the brand name Truxal.[17][18]

Availability

Chlorprothixene is widely available throughout Europe and elsewhere in the world.[17][18] The drug was previously available in the United States under the brand name Taractan, but this formulation has since been discontinued and the drug is no longer available in this country.[19]

References

- ↑ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ↑ Skov L, Johansen SS, Linnet K (Jan 2015). "Postmortem femoral blood reference concentrations of aripiprazole, chlorprothixene, and quetiapine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (1): 41–44. doi:10.1093/jat/bku121. PMID 25342720.

- ↑ Roth BL, BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Silvestre JS, Prous J (June 2005). "Research on adverse drug events. I. Muscarinic M3 receptor binding affinity could predict the risk of antipsychotics to induce type 2 diabetes". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (5): 289–304. doi:10.1358/mf.2005.27.5.908643. PMID 16082416.

- ↑ Haunsø A, Buchanan D (April 2007). "Pharmacological characterization of a fluorescent uptake assay for the noradrenaline transporter". Journal of Biomolecular Screening. 12 (3): 378–384. doi:10.1177/1087057107299524. PMID 17379857.

- 1 2 Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (November 1987). "Antagonism by neuroleptics of serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". European Journal of Pharmacology. 143 (2): 279–282. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(87)90544-9. PMID 2891550.

- 1 2 Roth BL, Craigo SC, Choudhary MS, Uluer A, Monsma FJ, Shen Y, et al. (March 1994). "Binding of typical and atypical antipsychotic agents to 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 and 5-hydroxytryptamine-7 receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 268 (3): 1403–1410. PMID 7908055.

- 1 2 Glusa E, Pertz HH (June 2000). "Further evidence that 5-HT-induced relaxation of pig pulmonary artery is mediated by endothelial 5-HT(2B) receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 130 (3): 692–698. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703341. PMC 1572101. PMID 10821800.

- ↑ Bylund DB, Snyder SH (July 1976). "Beta adrenergic receptor binding in membrane preparations from mammalian brain". Molecular Pharmacology. 12 (4): 568–580. PMID 8699.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 von Coburg Y, Kottke T, Weizel L, Ligneau X, Stark H (January 2009). "Potential utility of histamine H3 receptor antagonist pharmacophore in antipsychotics". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 19 (2): 538–542. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.012. PMID 19091563.

- 1 2 Seeman P, Tallerico T (March 1998). "Antipsychotic drugs which elicit little or no parkinsonism bind more loosely than dopamine to brain D2 receptors, yet occupy high levels of these receptors". Molecular Psychiatry. 3 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000336. PMID 9577836. S2CID 16484752.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bolden C, Cusack B, Richelson E (February 1992). "Antagonism by antimuscarinic and neuroleptic compounds at the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 260 (2): 576–580. PMID 1346637.

- 1 2 3 Csernansky JG (6 December 2012). Antipsychotics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 360–. ISBN 978-3-642-61007-3.

- ↑ Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, et al. (2011). "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623852K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. PMC 3166082. PMID 21909365.

- ↑ Healy D (1997). The antidepressant era. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-674-03958-2.

chlorprothixene antidepressant.

- ↑ Sneader W (2005). Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-471-89980-8.

- 1 2 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- 1 2 "Truxal".

- ↑ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products".